By Emily Petermann, Library Assistant

“Dear March—Come in—

How glad I am—

I hoped for you before—

Put down your Hat—

You must have walked—

How out of Breath you are—

Dear March, how are you, and the Rest—

Did you leave Nature well—

Oh March, Come right upstairs with me—

I have so much to tell—“

In 1846 — Decades before she became Amherst’s enigmatic recluse – a young Emily Dickinson visited Boston. She told her friend Abiah Root: “I left for Boston a week before last…I have both seen & heard a great many wonderful things…I have been to Mount Auburn, to the Chinese Museum, to Bunker Hill. I have attended 2 concerts, & 1 Horticultural exhibition. I have been upon the top of the State house & almost everywhere that you can imagine” [i]

Today, let’s enjoy some fresh March air and tour 1846 Boston, following in Dickinson’s footsteps.

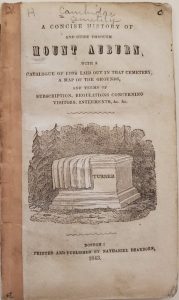

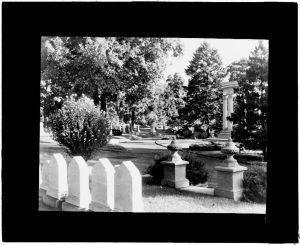

Let’s begin with Mount Auburn. Mount Auburn Cemetery was laid out to serve the Boston area in 1831 and had been open for 15 years when Emily Dickinson visited her Aunt Lavinia Norcross. Mount Auburn was the first of its kind in the country: a permanent resting place and pleasant place to visit, away from the ever-growing cities.[ii] The cemetery park design attracted many visitors like Emily, both mourners and people coming to enjoy the grounds. Visitors could wander around the numerous paths and enjoy the greenery. They could also buy a guidebook like this one by Nathaniel Dearborn, “A concise history of, and guide through Mount Auburn,” which details the history, lots, and occupants of Mount Auburn, along with the rules for visiting.

One of these rules, which may have slightly irked Dickinson, is that visitors to the cemetery were “prohibited from gathering any flowers, either wild or cultivated, or breaking any tree, shrub, or plant.”[iii] One of Dickinson’s greatest pleasures was gardening, and at time she visited Mount Auburn, she was finishing up her ‘Herbarium,’ a book, completed in 1846, in which she pasted pieces of plants with their everyday and scientific names. She seems to have thought highly of the grounds, telling Abiah “it seems as if Nature had formed the spot with a distinct idea of its being a resting place for her children, where wearied and disappointed they might stretch themselves beneath the spreading cypress & close their eyes ‘calmly as to a nights repose or flowers at set of sun.”[iv]

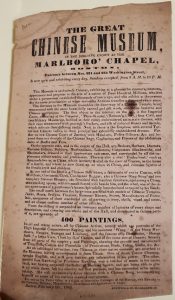

Dickinson also enjoyed a trip to the Chinese Museum. The Chinese Museum was a museum that ran from 1845-1847 in the Marlboro Chapel on Washington St., and was made up of objects, drawings, and featured the work of two Chinese men who entertained and educated visitors, all brought to Boston by a recent diplomatic mission.[v] It was created by John R. Peters, who would later sell the museum to P.T. Barnum. Peters also wrote a guidebook that we hold here at the MHS, which walks the viewer or reader exhibit by exhibit through the museum with an explanation, facts, and historical background of each tableau. Peters claims that “This collection was formed without reference to labor or expense, and with the aid of the Chinese and of the American Missionaries who have resided so long…”[vi] Visitors would have wandered past 25 cases illustrating daily life and culture, and viewed items such as musical instruments and money, and smelled incense burning. Dickinson was particularly impressed by the “endless variety of Wax figures made to resemble the Chinese & dressed in their costume.”[vii]

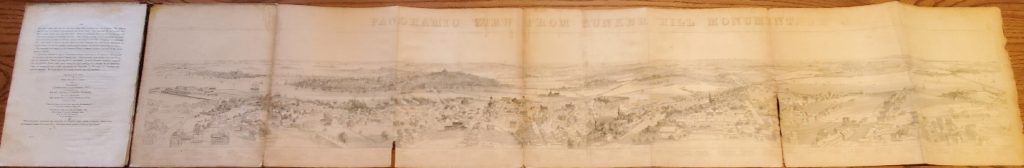

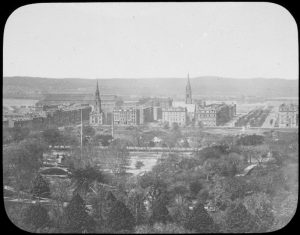

After that, Dickinson visited Bunker Hill. In 1846, the Bunker Hill Monument was only a few years old, and a popular tourist attraction. At its heart, a towering granite obelisk and a park dotted with memorials to those who had died at the Battle of Bunker Hill. Another great draw is the view from Bunker Hill, which is a panoramic scene over the city of Boston. Check out this engraved panoramic view of Boston from Bunker Hill in 1848. From here they could have seen the entire city of Boston stretching out below them.

For the next stop, we’re off to stop and smell the roses. On this day, Emily, Aunt Lavinia, and Cousin Louisa went to a Horticulture Exhibition for an “exhibition of fruits and flours.”[viii] The exhibition may have been held in the Horticultural Hall on School Street.

Perhaps they viewed the August exhibition of Dahlias that William Bordman Richards describes in his 1846 diary as “the best thus far I have been able to make.”[ix] Richards was especially proud of his ‘Cleopatra’ varietal, which was new to the Massachusetts Horticultural Society that year. Dickinson and her family may have wandered through the Walker & Co flower-seed store on their way out, picking up some of the new varietals of dahlias that were for sale, or some flower seeds to take home. We can wander through this seed shop through the Descriptive catalogue of flower-seeds for sale by Walker & Co.

In our final stop on the trip, we head to the top of the State House. The ‘New’ Massachusetts State House was built on Beacon Hill in 1798, to replace the older State House on State Street. We’re extra lucky in this stop, as someone took photos of the views from the top of the State House in every direction. What a view!

You can check out the MHS’s collection of photos and take in the best views that Boston had to offer here.

Dickinson returned home to Amherst after a month’s sightseeing in Boston, telling Abiah she had been “almost everywhere that you can imagine.”[x] Over the course of her life, Dickinson would write over a thousand poems—including the one featured in this blog post—and slowly become more and more reclusive, choosing not to travel, eventually avoiding leaving the house if possible. Instead, she focused on her poems. Only a handful of her poems were published during her lifetime; it was only after her death and her sister Lavinia Dickinson’s discovery of her work that they were published in 1890. The MHS holds a beautifully illustrated first edition of this poetry, which can be viewed here.

“Who knocks? That April—

Lock the Door—

I will not be pursued—

He stayed away a Year to call

When I am occupied—

But trifles look so trivial

As soon as you have come”[xi]

Find out more about Mount Auburn’s history from the Beehive!

If you’re in the neighborhood check out the Homestead, the Emily Dickinson Museum in Amherst, MA.

[i] “Letter from Dickinson to Abiah Root,” Dickinson Electronic Archive, last modified February 25, 2008, http://archive.emilydickinson.org/correspondence/aroot/l13.html

[ii] “Rural Cemetery Movement Grows.” Mount Auburn Cemetery, last modified October 25, 2014, https://mountauburn.org/rural-cemetery-movement-grows/

[iii] Dearborn, Nathaniel., A concise history of, and guide through Mount Auburn (Boston, N. Dearborn, 1843)

[iv] Dickinson Electronic Archive, “Letter from Dickinson to Abiah Root.”

[v] Zboray, Ronald J., and Mary Saracino Zboray. “Between ‘Crockery-Dom’ and Barnum: Boston’s Chinese Museum, 1845-47.” American Quarterly 56, no. 2 (2004): 271–307. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40068196.

[vi] Peters, John R., The great Chinese Museum, (Boston, Farwell & Co, 1846)

[vii] Dickinson Electronic Archive, “Letter from Dickinson to Abiah Root.”

[viii] Dickinson Electronic Archive,” Letter from Dickinson to Abiah Root.”

[ix] William Bordman Richards diary, Walcott family papers, Massachusetts Historical Society.

[x] Dickinson Electronic Archive, “Letter from Dickinson to Abiah Root.”

[xi] Dickinson, Emily, “Dear March—Come in–(1320),” Poets.org, accessed March 16, 2022. https://poets.org/poem/dear-march-come-1320

What a lovely article. I envisioned myself going on this tour and then you posted the sources for every spot. Very enjoyable. I hope to visit someday.

Wonderfully done piece. I do love history.

Such interesting history and a creative approach to follow in Emily Dickinson’s footsteps. I’ve been to Mt. Auburn and loved it and this makes me want to go back as well as visit the rest of Dickinson’s journey. Nice work!