By Susan Martin, Senior Processing Archivist

For today’s blog, I’d like to give you a behind-the-scenes peek at the work of archivists, specifically some of the small challenges we face in processing and preserving manuscripts for researchers. Collections come to us in all shapes, sizes, and physical conditions. While the work is interesting and rewarding, you may be surprised how long it takes to get a collection ready for use. Here are a few of the issues that make our jobs a little harder.

First, let’s talk about processing. Processing involves physically arranging a collection and describing its contents in a catalog record or collection guide. Imagine taking the carton shown above, removing all the letters from their envelopes, arranging them chronologically, identifying correspondents and subjects, etc. So, what are the most common hurdles?

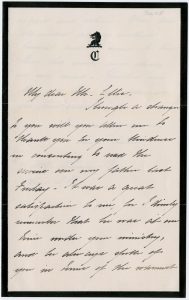

- Undated manuscripts. I give this issue pride of place in my list because of how common and how frustrating it is. Archivists may be able to date a letter based on a postmark (if we still have the envelope), a partial date, or internal clues, such as the passing mention of a recent event. The black border on the letter pictured here tells us a relative of the writer has recently died. However, archivists don’t read all the letters in a collection and seldom have time to do the digging necessary to date undated letters.

- Unattributed manuscripts. I’ve seen this primarily with diaries, which is understandable. After all, most people probably don’t think their diaries will ever be read by anyone else. (God forbid!) But so much information is lost without this context. Who was this person? What experiences did they live through? Like letters, diaries can often be identified with some investigation, but it’s time-consuming.

- Unidentified photographs. I wrote a few years ago about processing a large collection of family photographs and having to identify the baby pictures of three sisters who looked almost identical. We see so many terrific photographs come through our doors, it’s a shame when we can’t tell you who’s in them.

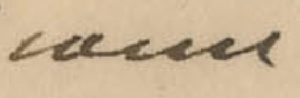

- Difficult/illegible handwriting. Archivists get better at this with practice, but it never really stops being tricky. If you’re responsible for processing a large collection of someone’s papers, you’ll become intimately familiar with their handwriting and the way they form certain letters, but then you’ll move on to the next collection and start all over again. Centuries-old writing sometimes barely even looks like English.

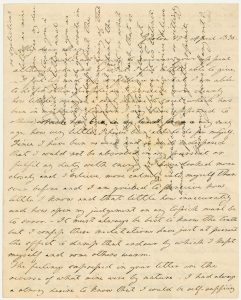

- Cross-writing. It was very common for correspondents, when they were running out of space but had a little more to say, to return to the first page and write across it at a 90-degree angle, as shown in this letter by Margaret Fuller. In this example, the end of the letter is right on top of the beginning. I’ve seen many variations of this, including writers who scribble along the margins or even turn a letter upside down and write in the gaps between the lines.

- Duplicate copies. For modern collections, one of the biggest problems is excessive duplication. A collection, particularly the records of an organization, will usually contain multiple photocopies of documents that take up unnecessary space and need to be weeded.

Next up is preservation, the key to the long-term survival of our collections. Preservation encompasses everything from conservation—the physical repair of individual documents—to temperature and humidity control, light management, and the selection of acid-free enclosures. It also includes all the little steps we processing archivists take to ensure that a given document lasts as long as possible.

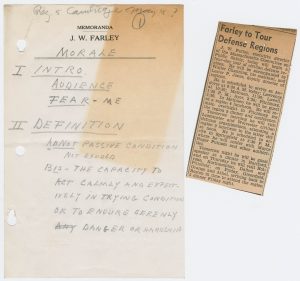

- Acidic paper. Newspaper clippings, as they deteriorate, will not only become more brittle themselves, but they’ll also emit acid that does the same thing to the papers that touch it. You’ll see the pattern of staining on documents that have lived next to clippings for a period of time. It’s not just newspapers, either; the same kind of poor-quality wood-pulp paper was used for telegrams and some 20th-century copy paper. MHS archivists generally, time-permitting, photocopy newspaper clippings and remove the originals, or at least isolate any acidic paper.

- Onion-skin paper. This unmistakable thin paper was common in airmail because of its light weight. It was also used for carbon copies of typed business correspondence. The ink on these copies is frequently faint to the point of illegibility, and the paper tears very easily.

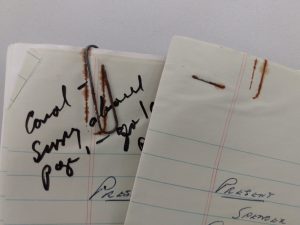

- Metal fasteners. Ah, staples and paper clips. I often think archivists should be sure to keep up with their tetanus shots. Some past recordkeepers even used straight pins to attach pages together. And if a collection has been kept in a damp and/or warm environment before coming to the MHS, the rust (and rust stains) resulting from these metal fasteners can be epic. Rubber bands get an honorable mention here, too, because as they dry and harden, they will also stain paper. When fasteners are necessary, we use plastic paper clips.

- Post-it® notes, tape, and other forms of adhesive are dangerous for paper even after they’ve been removed. Some residue of the adhesive remains on the paper and will damage it over time. Best to avoid them altogether.

- Red rot. Red rot is what happens to leather that has been exposed to humidity and/or high temperatures. This image shows how poor the condition of leather-bound volumes can become. Red rot is also, as any archivist or special collections librarian can tell you, a huge mess; it will crumble onto shelves, desks, your clothes, everything. Volumes that are literally falling to pieces can’t be handled by researchers, so the MHS measures each volume and orders custom-fitted cases.

- Organic material. More than a few collections contain other forms of organic material, such as leaves and flowers pressed into volumes, as well as locks of human hair. These items are removed.

This is only a partial list; I haven’t mentioned digital records or issues related to the reference side of things. If my fellow archivists or librarians out there want to add anything in the comments, you’re more than welcome!

THANK YOU FOR TAKING THE TIME TO POST THIS I DO CALLIGRAPHY AND HAVE MANY OLD BOOKS. THIS SEEMS SO INTERESTING AND GIVES SO MUCH VALUABLE INFORMATION ON TRYING TO PRESERVE OUR HISTORY AS A MEMBER OF A HISTORICAL COMMISSION TRYING TO PRESERVE OUR OWN COLLECTIONS i THINK THE ARTICLE IS VERY HELPFUL AND YOU SHOULD BE COMMENDED FOR ALL YOUR HARD WORK