By Susan Martin, Senior Processing Archivist

I recently had the opportunity to do some fun detective work when an unidentified diary was donated to the MHS.

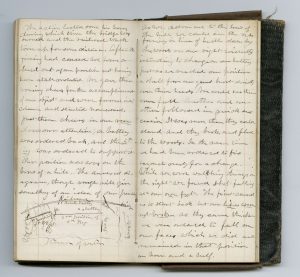

The diary was kept in a small leatherbound volume, just 6 by 3.5 inches, very typical of its time. It describes a Northern soldier’s Civil War service between 10 September 1862 and 8 June 1863, primarily at New Bern, North Carolina. The pages are clean, the handwriting neat and legible, and the content very interesting. But who kept it? There’s no inscription or other identification.

I started by skimming the diary for some names and dates. The writer tells us on the first page that he enlisted as a private in the 5th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, Company I, “having felt it [his] duty to serve [his] country in some way in this its hour of need.” On subsequent pages, he refers to a son Eddie and a wife Martha. He mentions his wedding anniversary on 16 Oct. 1862.

Fortunately, archivists and historians have a terrific resource in the nine-volume reference work Massachusetts Soldiers, Sailors, and Marines in the Civil War, published in the 1930s. This work lists, by regiment, all the soldiers from Massachusetts known to have served in the war.

To identify our mystery man, I started with a guess: maybe his son Eddie was his namesake. Well, according to Massachusetts Soldiers, Company I of the 5th Mass. Infantry included six privates named either Edward or Edmund. Online searches on each of them turned up nothing that corresponded to the diary. None of them, as far as I could tell, had a wife Martha or a son Eddie. At least one never married. The father of another died before the war (and our diarist wrote about his very-much-still-alive father).

The diary, in fact, has nothing in it to indicate our writer was an Eddie, Sr., so I dropped that hypothesis and went back to the text for a closer look. I noticed repeated references to people with the surname Wright. Was he a Wright? There were four Private Wrights in the company. But one thing gave me pause: “Father Wright,” which appears in several diary entries, sounded more like a father-in-law than a father. So I guessed that the Wrights were his wife’s family. Unfortunately, searches for “Martha Wright” also came up dry.

Other tantalizing but ultimately unhelpful clues included the name of a sister (or sister-in-law) Mary and the towns of Marlborough and Shrewsbury, Mass. None of these details were specific enough to narrow my search. I kept feeling like I was getting close, only to hit another dead end.

Eventually I came across a pivotal diary entry dated 27 Oct. 1862: “Our tent mess is composed of Geo. Fogg, E. E. Wright, C. W. Hill, W. W. Wood, J. F. Claflin, A. E. Wright, J. D. Barker, Frank Bean, Charles Adams, Geo. Works, A. L. Nourse, J. W. Barnes, Eph. Howe, E. A. Perry.” These are all names of men in Company I. Assuming our writer included himself in this list (albeit in the third person), I finally had a short list to work from. I eliminated a few fairly quickly—those mentioned in other diary entries, for example—but still couldn’t make a positive identification.

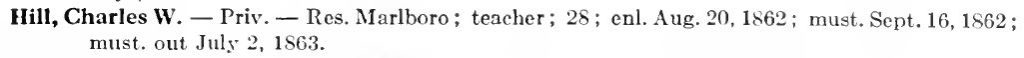

Then I discovered I’d made a critical mistake. As neat as our diarist’s handwriting was, I had misread one name. What I initially thought was Wright…was actually Wight. This was the proverbial break in the case. An online search for “Martha Wight” eventually led me to a family genealogy published in 1890. There she was at the bottom of page 280: Martha Eleanor Wight married Charles Willard Hill, of the 5th Massachusetts Infantry, on 16 October 1856. The couple’s oldest son, Edward Albert Hill, was born in 1857.

It was short work to verify all the details. Hill’s was one of the names listed in the “tent mess” above. Family members and towns in the diary checked out, as did the diary entry for Hill’s birthday, 5 June. I finally had my man.

Hill had been a teacher before the war and would return to it afterwards, eventually serving as headmaster of the Comins School in Roxbury and the Bowditch School in Jamaica Plain. Based on his diary, he was a very religious person and a loving husband and father. His entry about saying goodbye to his five-year-old son is particularly touching.

My parting with my dear Eddie was in the road near Father Wight’s house. The dear little fellow seemed fully to appreciate that I was going away for a long time. He said afterwards that he went back to the place alone to see if he could not see me again. I am glad I did not know of it at the time, as it would have unmanned me.

On 1 January 1863, Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation freed enslaved people in the Confederate states. That same month, Hill was detailed to work with the “superintendent of the freedmen” at New Bern. Hill spent his days answering questions, distributing donations, and writing passes. He loved the job and often expressed his wish to be of service to African Americans in the South.

Who was this superintendent of the freedmen? Well, in Hill’s diary, and even in the published history of the regiment, he’s just “Rev. Means.” It looked like I had a second mystery on my hands.

Fortunately, this one was much easier to solve. All it took was some creative keyword searching to find hospital chaplain James Means (1813-1863). Means’s many affiliations included Andover Theological Seminary, Middlesex County Temperance Society, Lawrence Academy, Spingler Institute, Tilden Female Seminary, and Lasell Seminary. (The MHS holds some of his correspondence in the Amos Lawrence and Amos Lawrence III papers.) Means was an inspiration to Hill, but he died just a few months after they met. Hill was apparently present at his death.

We’re grateful to our donors for all the terrific manuscripts they have sent us over the years! And we hope many researchers will come and take a look at the Charles Willard Hill diary for themselves.

Now THIS, this is why I come here: ‘tell me a story’. Marvelous use of sources to track down historical memories, memoirs, and people. (I wish I had your job!) Thank you.