By Gwen Fries, Adams Papers

Abigail Adams’s death on 28 Oct. 1818 represented a cosmic shift in the Adamses’ universe. As her daughter-in-law Louisa Catherine Adams explained, Abigail was “the guiding Planet around which all revolved, performing their separate duties only by the impulse of her magnetic power.”

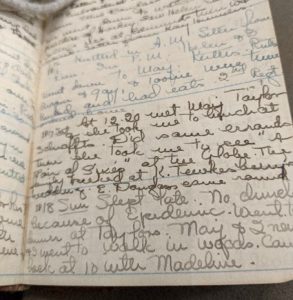

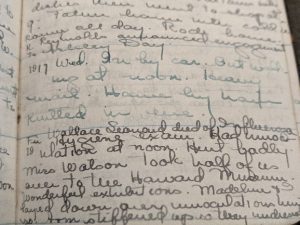

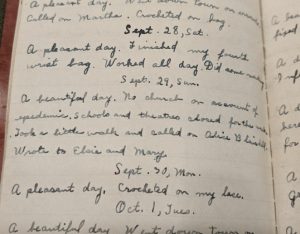

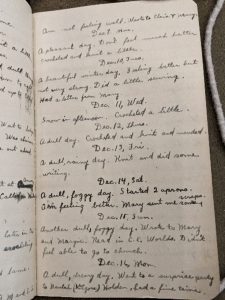

Though her death touched every member of the family, John Quincy Adams, then in Washington, D.C., knew his 83-year-old father would be the most affected. On 1 November, having received notice that his mother was gravely ill, he wrote in his diary, “Oh! what must it be to my father, and how will he support life without her who has been to him its charm?”

The next day, John Quincy received confirmation of his mother’s death. He retired to his chamber to weep and then reflected on what this loss would mean to his father.

“She had been fifty four years the delight of my father’s heart; the sweetener of all his toils—the comforter of all his sorrows; the sharer and heightener of all his joys— It was but the last time when I saw my father that he told me . . . that in all the vicissitudes of his fortunes, through all the good Report, and evil Report of the World; in all his struggles, and in all his sorrows the affectionate participation, and cheering encouragement of his wife, had been his never failing support; without which he was sure he should never have lived through them.”

John Quincy wrote to his father, lamenting their mutual loss and assuring his father it was “the dearest of his wishes to alleviate” John’s pain. “Let me hear from you, my dearest father; let me hear from you soon.” On 3 November, John Quincy repeated to his diary, “It is for him, and to hear from him that my anxiety now bears upon my mind.”

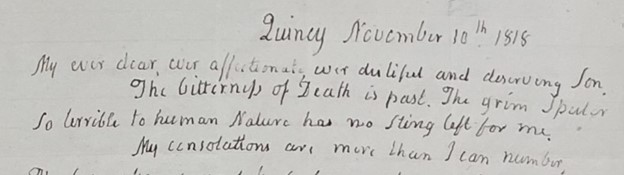

On 10 November, John Adams responded to his “ever dear, ever affectionate, ever dutiful and deserving Son.” He wrote that “The bitterness of Death is past. The grim Spector So terrible to human Nature has no Sting left for me.” Knowing John Quincy was agonized to be separated from his father at such a painful juncture, John reassured him that “the Sympathy and Benevolence of all the World, has been Such as I Shall not live long enough to describe” and that his “consolations are more than I can number.”

John Quincy wrote to his last-surviving sibling, Thomas Boylston Adams, on 22 November. “I have received a short Letter from our dear and honoured father, and have heard from various quarters of the fortitude with which he has met the most distressing of calamities. Knowing his character as I do this was what I expected.” John Quincy confided to his brother that he still fretted for their father. “The struggle which is not apparent to the world, is not the less but the more trying within— Watch over his health, my dear brother with unremitting, though if possible to him imperceptible attention. Assist him with unwearied assiduity in the management of his affairs; and always according to his own deliberate opinions and wishes.” He stressed this last point. “Let the study of every one around him be to gratify his wishes, according to his ideas, and not according to their own.”

Indeed, John Adams had lost the person who most carefully watched over his health and affairs, but it was the loss of Abigail’s constant company and conversation John felt most severely. Though Adams put on a brave face for his family—his letters from this period are filled with levity and self-deprecating jokes—his boredom and loneliness saturate the page.

John Quincy couldn’t leave Washington, so he dispatched his eldest son, George Washington Adams, to Peacefield during Harvard’s winter break. “He is fond of your company,” John Quincy wrote to his son. “You can render yourself very serviceable to him; and . . . you can be in no possible situation better adapted to the improvement of your heart and the cultivation of your Understanding than with him.”

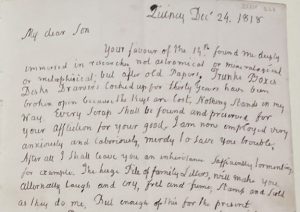

In December 1818, the bereaved patriarch and his grandson embarked on a project that thrills the heart of this editor. The two Adamses tore Peacefield apart in search of family papers. “Trunks Boxes Desks Drawers locked up for thirty Years have been broken open because the Keys are lost. Nothing Stands in my Way. Every Scrap Shall be found and preserved.”

Though John Adams had been kicking around Peacefield since 1801, it was the loss of Abigail that stimulated this frenzied search. Perhaps her death made him reflect on his own mortality and legacy. Perhaps he just needed a project to keep him busy. But I wonder if the quest to find old family letters wasn’t a grieving widower seeking the company and conversation of his dearest friend.

The Adams Papers editorial project at the Massachusetts Historical Society gratefully acknowledges the generous support of our sponsors. Major funding is provided by the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Historical Publications and Records Commission, and the Packard Humanities Institute. The Florence Gould Foundation and a number of private donors also contribute critical support. All Adams Papers volumes are published by Harvard University Press. Major funding for the John Quincy Adams Digital Diary was provided by the Amelia Peabody Charitable Fund. Harvard University Press and a number of private donors also contributed crucial support.