By Lucy Wickstrom, Adams Papers Intern

Like many younger siblings, Thomas Boylston Adams experienced a combination of gratitude and annoyance at his older brother John Quincy’s protectiveness. In the autumn of 1794, they voyaged together to Europe, where John Quincy was to work as foreign minister to the Netherlands with Thomas as his secretary. As they approached the chalky cliffs of Beachy Head, Thomas climbed to the highest part of the ship’s mast in order to get a better view — a stunt the twenty-two-year-old only felt comfortable performing because his brother was not “upon Deck.” In his diary (M/TBA/1, Adams Papers), Thomas confessed, “I should hardly have done it in his presence lest his fraternal solicitude about my discretion and safety” cause an embarrassing scene for them both. Thomas admitted that he felt “grateful for his tenderness…on many occasions,” but could not help but wonder why John Quincy seemed to think he lacked his own sense of “self preservation.”

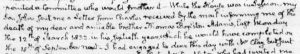

John Quincy’s concern for his youngest brother would not subside. After four years in Europe together, during which Thomas had been his brother’s “constant companion,” the younger Adams sailed back to the United States to resume his law practice in Philadelphia – a decision which his concerned sibling had some thoughts about, as well. “I do not think…his inclination…suited to the contentious part of that profession,” John Quincy wrote to their mother shortly after parting ways with Thomas. He saw in his younger brother an incredible mind and talent, who could be a “valuable…citizen of his Country,” but believed that law may be too fierce a profession for Thomas’s more sensitive nature. John Quincy’s judgment proved prophetic, as Thomas struggled to find much success as a lawyer, instead preferring to spend his time writing and publishing political pieces for Philadelphia newspapers and the literary journal Port Folio. He even wrote to his father, John Adams, on 22 October 1799 (Adams Papers) that he feared his “strong natural want of confidence” in himself ensured his failure in the field of law.

Whether Thomas was ever aware of that prescient piece of “fraternal solicitude” is unclear, but he certainly continued to reap the benefits – and, presumably, the inconveniences – of John Quincy’s anxiety for the rest of his life. And after a varied career in the early part of the nineteenth century that included service in local politics, on the Massachusetts state legislature, and as a circuit court chief justice, the youngest Adams sibling began to give his brother significant cause for worry. “If in any instance I have…wounded your feelings I am sorry for it,” the elder Adams wrote gently in 1818, entreating Thomas “to be kind to yourself.”

Thomas was showing signs of having inherited the same struggle that plagued both his maternal uncle and his brother Charles before him, as alcohol addiction damaged his health and put a strain on many of his familial relationships. The youngest Adams sibling, formerly applauded by relatives and acquaintances for his genial personality, became what his nephew Charles Francis Adams described as “a bully in his family” through the effects of his disease. Disliked, feared, or ignored by many of his loved ones, Thomas retained a consistent ally in John Quincy, who provided financially for not only his younger brother but Thomas’s wife and six children, as well. It was, according to John Quincy, merely his “brotherly duty of kindness.”

One of the first extant letters from John Quincy Adams to his youngest brother was penned in Paris, where the ten-year-old had traveled with their father, and addressed “To My Brother Tommy.” John Quincy reminded his five-year-old sibling that, difficult as it may be to accept, “Providence…has seperated us so that we cannot expect to see one another very soon.” Yet after the separations of their childhood, the brothers were hardly ever apart: partners in business, intimate confidants, close companions — and, finally, provider and dependent.

And when, on 12 March 1832, Thomas Boylston Adams died, his devoted sibling — now the only surviving child of John and Abigail Adams, the last remaining member of his famous immediate family — turned to his trusty diary to mourn the “dear and amiable brother” whom he loved.

Lucy Wickstrom interned with the Adams Papers in fall 2021. She is a graduate student at Tufts University, where she is pursuing her master’s degree in history and museum studies, with a special interest in early U.S. history and all things Adams family.

great job as always, Lucy. So very proud of you and your love of history

That was a very interesting read. Thank you for bringing their writings to life.

Good to see you are still writing!!