By Jenna Colozza, Library Assistant

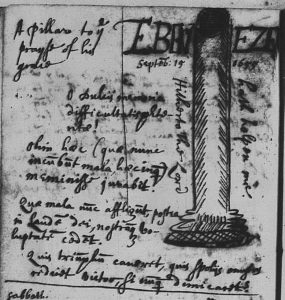

In February of 1653, twenty-one-year-old Michael Wigglesworth listened as Henry Dunster, clergyman and president of Harvard College, gave a sermon at the public assembly. But Wigglesworth was distracted from the sermon. Instead, he was fretting over one of the students he tutored at Harvard who was absent from the assembly due to illness. Later, reflecting on the day, Wigglesworth wrote in his diary:

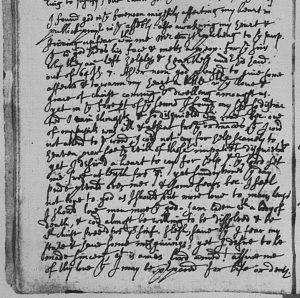

“I feel not [love] to god as I should, but more [love] to man, least I should [love] man more than god. I am laden with a body of death, and could almost be willing to be dissolved and be with christ free’d from this sinful flesh.”

Why did this young man feel so terrible for worrying about his pupil? The answer may lie in coded diary entries. In these entries he wrote about having feelings of love and desire (what he called “unnatural filthy lust”) for his male pupils.

In 1653 Wigglesworth was a fellow at Harvard College, from which he had graduated in 1651. He was assigned to a group of freshmen, the class of 1656. The students ranged in age from about 13 (the young Increase Mather) to 27, the majority being teenaged.

Perhaps some of the guilt he felt for his desire toward his students was due to the age and power difference between them, and his responsibility for both their academic and their spiritual development. (Richard Crowder, who published a biography of Wigglesworth in 1962, reports that as a student Wigglesworth was “fondly attached” to his own Harvard tutor.[1]) Furthermore, to put it lightly, Puritans frowned upon same-sex desire and acts. Laws prohibiting sodomy classified it as a capital punishment—though it was seldom prosecuted to the full extent of the law.[2]

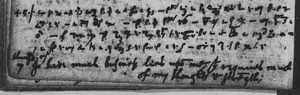

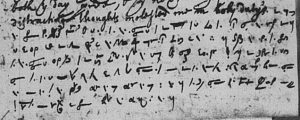

For these reasons, it makes sense why Wigglesworth would want to write portions of his diary in code. The code he used was based on a stenography shorthand. It was quite popular at the time and used for both personal and business purposes, but Wigglesworth made his own alterations to the code which would have made it more difficult to decipher.[3] This must have allowed him the peace of mind to write without fear of someone stumbling across the diary and reading his most intimate secrets.

Puritans hold a peculiar place in the modern imagination. They are stereotypically portrayed as fixated on sin and delighting in punishment. And this particular Puritan seems to lend himself rather unfortunately to stereotype. His name alone sounds laughably quaint and silly to the modern ear. Because of his diary, Wigglesworth has been described as overwrought, neurotic, a distillation of Puritanical anxieties. One notable entry sees him worrying over whether he has a duty to let his neighbors know that their stable door is blowing open in the wind as if it is a life-or-death situation. Many of the entries read the same way, whether about pride, lust, or some other perceived shortcoming.

But Wigglesworth’s diary was actually quite typical in its anxious fixation on sin. Diaries like his were a common method of religious devotion for Puritans. The purpose was for the diarist to meditate on their sins to come to a greater assurance of salvation through divine grace. And Wigglesworth indeed used his diary as a place to wrestle with his feelings about his pupils. He wrote in one entry, “I find my spirit so exceeding carried with love to my pupils that I cant tell how to take up my rest in God.”

His love for his pupils often took the form of deep concern for their religious development. In one instance, he wrote about a pupil whom he had instructed to focus solely on schoolwork and religious devotion. Upon seeing the student enjoying music the next day, he wrote, “For these things my heart is fill’d and almost sunk with sorrow and my bowels are turned within me.” His identification with the sins of others, their physical effect on his body, seems appropriate (if rather intense) for an aspiring minister. Yet worrying over his pupils’ souls also evoked guilt—he once wrote, “whilest I seek him for others I loose him and my love to him my self.”

The pain and suffering he experienced was also quite literal, as Wigglesworth was in ill health for much of his life. He frequently complained of being prone to colds, bouts of weakness, and “rhewms.” He appealed in one entry, “heal my soul and body for both are very loath and unable to do thy service.”

Though his diary describes almost unrelenting physical and spiritual struggles, to his contemporaries he was a man of high spirits. He was described in an 1863 biographical sketch by nineteenth-century historian John Ward Dean as “[seeming] generally to have maintained a cheerful temper, so much so that some of his friends believed his ills to be imaginary.” Cotton Mather remarked in Wigglesworth’s eulogy that

“He used all the means imaginable, to make his Pupils not only good Scholars, but also good Christians; and instil into them those things, which might render them rich Blessings unto the Churches of God. Unto his Watchful and Painful Essayes, to keep them close unto their Academical Exercises, he added, Serious Admonitions unto them about their Interiour State, and (as I find in his Reserved Papers) he Employ’d his Prayers and Tears to God for them, & had such a flaming zeal, to make them worthy men, that, upon Reflection, he was afraid, Lest his cares for their Good, and his affection to them, should so drink up his very Spirit, as to steal away his Heart from God.”

It is striking to see Mather’s complimentary interpretation of something that caused Wigglesworth such grief. Mather mentions having had access to Wigglesworth’s “Reserved Papers” and appears to quote from the diary in an appendix to the published eulogy. Could he make sense of the shorthand? His father was one of Wigglesworth’s pupils. Would he have still made special mention of Wigglesworth’s time as a tutor if he had discovered the coded passages? It is difficult to say, but it seems possible that the shorthand indeed preserved some of Wigglesworth’s privacy.

Michael Wigglesworth’s diary only covers a short period of his life. Nearly ten years after he began writing it, he would go on to publish his apocalyptic poem Day of Doom, which has been called the first American bestseller. He was married three times, had several children, and had careers in medicine and in the ministry until his death in 1705. The MHS holdings contain collections of materials representing many of Wigglesworth’s descendants. Yet the diary he kept as a young man survives as a record of his pained meditations—and it affords us some historical insights into one man’s personal experience of same-sex desire in seventeenth-century New England.

Sources

Dean, John Ward. Sketch of the Life of Rev. Michael Wigglesworth, A.M.: Author of the Day of Doom. Albany: J. Munsell, 1863.

Mather, Cotton. A faithful man, described and rewarded. Microfiche, Massachusetts Historical Society, 1213 Evans fiche.

Michael Wigglesworth diary, 1653-1657. Pre-Revolutionary War Diaries, microfilm, Massachusetts Historical Society, P-363 reel 11.19.

[1] See Richard Crowder, No Featherbed to Heaven: A Biography of Michael Wigglesworth, 1631-1705 (United States: Michigan State University Press, 1962), p. 32.

[2] See Robert F. Oaks, “‘Things Fearful to Name’: Sodomy and Buggery in Seventeenth-Century New England” (1978), Journal of Social History 12 (2).

[3] Edmund S. Morgan published a transcription of the diary in 1965 in which he decoded the shorthand passages. See Edmund S. Morgan (Ed.), The Diary of Michael Wigglesworth 1653-1657: the Conscience of a Puritan (United States: Harper, 1965).