By Benjamin D. Remillard, University of New Hampshire, Benjamin F. Stevens Fellow, MHS

Seeking opportunity and community following the War for Independence, growing coastal hubs like Boston became attractive destinations for free people of color. Many of these residents and recent migrants were engaged members of their communities. Cato Newell, for instance, was a twenty-three-year-old baker from Charlestown, MA, when he enlisted alongside the rebels after the violence at Lexington and Concord.[1] Boston’s Wenham Carey was a bit older by comparison, enlisting multiple times for short periods when he was already in his thirties.[2] Luke (or Luck) Russell, meanwhile, while not a veteran, is believed to have been a member of Prince Hall’s growing African Freemason Lodge.[3]

Life after the war, however, did not come without risks. Newell, Carey, and Russell discovered this for themselves when they were hired by a man named Avery to make boat repairs in February 1788. They travelled to Boston Harbor’s Long Island, where their employer directed the trio below deck to begin their work. After locking away his human cargo, the ship’s captain set sail for warmer waters.

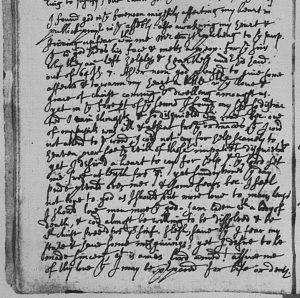

It was not long before word of the abduction reached the men’s families. Writing from Charlestown, they decried the capture of those “three unhappy Africans,” and insisted that their loved ones were “justly intitled” to “the protection of the laws and government which they have contributed to support.”[4]

The news “roused the spirit of all consistent advocates for freedom.”[5] Heeding the outcry, Gov. John Hancock and Philippe André Joseph de Létombe—the French Consul at Boston—alerted governors around the Caribbean and the South of the crime. Other civically engaged Bostonians similarly sprung to action when the Quakers, about 90 clergymen, and Prince Hall submitted petitions to the Massachusetts legislature.

The clergymen’s petition was couched in the Revolutionary era’s language of “universal liberty.” They were especially interested in banning American involvement in the international slave trade, framing it as an “inglorious stain upon our national character.”[6]

Hall’s petition, meanwhile, was personal, asserting that this was not the first time this happened. He claimed that “maney of our free blacks that have Entred onboard of vessles as seamen and have ben sold for slaves,” and that only “sum of them we have heard from.” Fearing similar fates, “maney of us who are good seamen are oblige to stay at home.”[7]

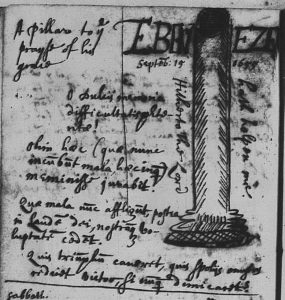

While Jeremy Belknap referred to Hall’s petition as an “original and curious performance,” they and the Quakers’ combined efforts produced a change.[8] On March 26, 1788 an act passed “to prevent the Slave Trade, and for granting Relief to the Families of such unhappy Persons as may be Kidnapped or decoyed away from this Commonwealth.”

Meanwhile, the kidnapped Bostonians arrived at Saint Barthélemy, in the Caribbean, and protested to anyone who would listen that they were free men. Perhaps miraculously, Governor Pehr Herman von Rosenstein interceded to stop their sale into slavery. Unfortunately, the island’s laws were “greatly to their disadvantage in all kinds of Disputes between them and White Persons.” Despite those restrictions von Rosenstein was “obliged” to detain (and thus save) the Bostonians until they “procured sufficient and authentic proofs of the Right of their Cause.”[9]

Hancock’s initial efforts came to fruition in the ensuing months, finally reaching von Rosenstein. Massachusetts’s governor assumed the costs to return the kidnapped men home in July 1788, and Newell, Carey, and Russell were welcomed home to a “jubilee.”[10] After surviving the threat of enslavement, the three understood as well as any how precarious life could be on the margins of early American society. The support they garnered from Boston’s different communities, however, also documents the growing wave of abolitionism and support for free Black Americans spreading across the Northeast.

[1] Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors of the Revolutionary War, v. 11 (Boston, MA: Wright & Potter Printing Co., State Printers, 1896-1908): 345 [MSS], MHS.

[2] MSS v. 3: 179-180, for the entries for Cary, Windham/Wenham/William.

[3] Sidney Kaplan and Emma Nogrady Kaplan, The Black Presence in the Era of the American Revolution (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 1989), 209.

[4] James Russell, Richard Cary, Elipha. Newell, “Advertisement,” The Massachusetts Gazette, 7 March 1788, AHN, though the piece was written 20 February.

[5] Belknap to Hazard, 17 February 1788, in Jeremy Belknap Papers, Part II (Boston, MA: Published by the Society, 1877), 19-20, MHS.

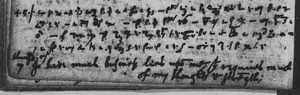

[6] Belknap to Hazard, 2 March 1788, Belknap Papers, II, 21-3, MHS.

[7] Hall to the Massachusetts General Court, February 27, 1788, https://www.masshist.org/database/viewer.php?item_id=670&br=1.

[8] Belknap to Hazard, March 2, 1788, Belknap Papers, II, 22, MHS.

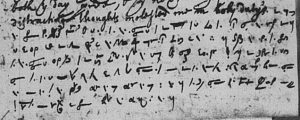

[9] von Rosenstein to Hancock, 6 July 1788, Miscellaneous Bound 1785-1792, MHS.

[10] Belknap to Hazard, August 2, 1788, Belknap Papers, II, 32, MHS.