By Susan Martin, Senior Processing Archivist

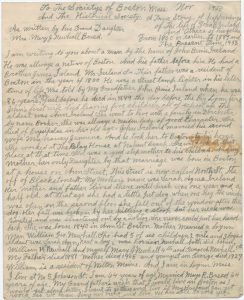

I recently stumbled on a fascinating document in the collections of the MHS that I’d never seen before, and once I started reading it, I couldn’t put it down. It’s a twelve-page family history, written neatly in thick pencil, called “A True Story of happenings of The life of John B. Ireland And Others of his folks From 1800 or earlier to 1889 and The Present Time, 1933 As written by his Grand Daughter Mrs. Mary J. Newhall Breed.”

Mary Breed wrote in a stream-of-consciousness style, recounting events out of order, often circling back and repeating herself, which makes reading this manuscript feel like sitting on a front porch listening to her talk. Some of the details are sketchy, but her family’s story is moving and at times tragic. I’ll do my best to summarize it here.

Mary J. Newhall was born in Lynn, Mass. on 27 February 1869, the daughter of Sarah Agnes (Ireland) Newhall and William George Newhall. William worked variously as a fisherman, as a field hand, and in the spice mills of West Lynn. He died in 1881, leaving Sarah with three children to bring up. Mary left school at 15 or 16 (she’s inconsistent on this detail) to work at the Lynn shoe factories and support her mother, whose health was bad. When her mother died in 1905, Mary kept house for her younger brother George until his death in 1927. Five years later, at the age of 63, she met and married Mayo Ramsdell Breed.

Mary had apparently lived all her life in Lynn, but her family’s ties to Boston went back generations. In her narrative, she mentions her great-grandfather, a street lamplighter; her grandfather John, a blacksmith and wheelwright; and she describes incidents in both her mother’s and her father’s lives and those of her in-laws.

I was particularly struck, though, by the story of her grandmother Nancy, which sounds like the plot of a BBC period drama, albeit told in Mary’s inimitable voice. Here is the relevant section (I’ve added paragraph breaks):

At the age of seven, my grandmother was bound out to a woman who kept a Sailor Boarding House near the old South Church in Boston. […] Nancy Jennins was one of five children who was brought over from England on the Sailing Vessel. Her Father followed the Sea as a Ship Rigger fixing the sails. She remembered when her mother left her with the Woman to keep her until she was 18 years of age. And she saw her mother go away with her little Brothers and Sisters, and she never saw her mother again.

Then one day the big Ship came into Boston Harbor. And little Nancy went to see her father, as she had done before when his Ship came in. But that last time she saw her father way up in the rigging fixing the sails and as she looked up she saw her father fall from the place where he had been at work into the water, she saw the sailors bring her father onto the shore dead. She ran home and cried. So she had nobody to love and care for her.

The Mistress of the Sailor Boarding House was not kind to Nancy. She made her work hard in the kitchen where she learned to cook everything. The Sailors were mostly bad men they carried swords and pistals [sic] in their belts, and she said some of them were kind to her, and they would give her presents, and some of the sailors were cross and wicked, she was afraid of them, but she had to wait on them or get a beating.

One day, Nancy was working in the kitchen and overheard her mistress, as Mary calls her, tell a neighbor that the following day was Nancy’s eighteenth birthday—in other words, the day she was a legal adult and free from her indenture. The mistress confided to the neighbor that she was keeping this fact from Nancy because she didn’t want to lose such a good servant.

Apparently Nancy didn’t know her birthday, or perhaps hadn’t understood that she was free to leave at eighteen. So she rose early the next morning, packed up everything she owned, and walked out of the house. Her mistress tried to stop her, but “Nancy told her that she was going to get work and take care of herself.”

She took a job as a cook for a family in Boston, as this was “the only work that she ever learned.” She married an Englishman named Barrily, who died in a shipwreck. She married again (I think this was Mr. Jennins), but was abandoned by this second husband after two or three years. And if all that wasn’t enough…

She had a pretty little baby boy by him, she carried him around in a covered basket, he was so little. […] But Nancy had to go to work and earn her living. So one day A Minister came along and he saw the baby boy. So he told Nancy how that his wife had a baby boy, and it died. He asked her if she would let him adopt the baby for his wife so she gave her consent to let the baby go and have a good home. The Minister and his wife were so pleased with the baby that they loved him and gave him everything a boy could wish for. But the boy only lived to be thirteen years of age he was all ways delecate [sic] and they felt badly to loose [sic] the little fellow.

Sometime in the 1830s, while working as a cook at the Relay House in Nahant, Nancy met the eponymous John Bemis Ireland, who became her third husband.

He rode to Lynn and Nahant on a white horse with a tall hat on, as men wore those days, to get her good dinners, that she used to cook. He liked her cooking so one day he asked her to marry him. She did.

John’s first wife had died, and he had five school-aged children. It’s a little unclear in Mary’s telling, but it seems that John lied to Nancy and told her his children were dead. Well, she married him and became “a good stepmother” to them. She and John would have one daughter together, Sarah Agnes, Mary’s mother.

I’ll pick up Mary’s story again here at the Beehive, so stay tuned!