By Susan Martin, Senior Processing Archivist

For this Thanksgiving Day, I scoured our catalog for material related to the holiday that hasn’t been covered on the Beehive before, but nothing grabbed my attention. It occurred to me that I might write something about gratitude in general, but all I turned up were printed sermons on the subject and personal correspondence thanking people for gifts. However, keyword searching led me, serendipitously, to abolitionist Thankful Southwick, so I thought I’d use this Thanksgiving Day to introduce you to this remarkable woman.

Now, the name Thankful is nothing new to archivists and historians in New England. We see a lot of these “virtue names,” mostly given to girls. Faith, Hope, and Charity are all very well, but my least favorites are definitely Silence and Submit.

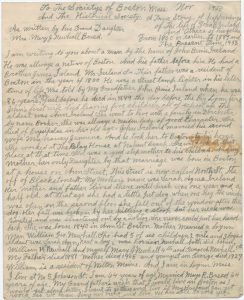

Thankful was born in 1792 in Portland, Me., the third daughter of Samuel Fothergill Hussey and Thankful (Purinton) Hussey. (You couldn’t make these names up! One author calls Thankful Hussey a “quite unreasonable but none the less interesting name.”) Samuel was a prosperous merchant in Portland, and the elder Thankful was a well-known Quaker minister. Both were heavily involved in anti-slavery work. Legend has it that Samuel helped freedom seekers escaping on ships from the West Indies to get to Canada.

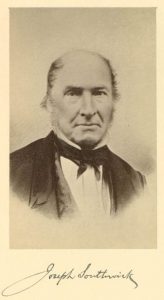

In 1818, the younger Thankful married Joseph Southwick, a tanner. The couple had three daughters in quick succession, Abigail, Sarah, and Anna. In 1834, the family moved to South Peabody (now Danvers), then to Boston in 1835.

The 1830s were a time of exponential growth in the abolitionist movement, and the Southwicks were in the thick of it. Joseph was one of the original subscribers to William Lloyd Garrison’s fiery Liberator, as well as a founder of the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1833, serving alternately as president and vice-president for its first 15 years.

Thankful, not to be outdone, was herself a member of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, president of the society several times in the 1840s, and a proponent of women’s rights. All three of her daughters became anti-slavery activists, including Sarah Hussey Southwick, who got involved in the movement at the age of 13. The Southwick home was also part of the Underground Railroad.

Thankful was a participant or an eyewitness at several notorious incidents during the antebellum period, including the attack on William Lloyd Garrison by a Boston mob in 1835. She was also present at what’s been called the “Baltimore Slave Case” or the “Abolition Riot” of 1836.

The case began when Eliza Small and Polly Ann Bates, two Black women, arrived in Boston on a ship from Baltimore. Although they may have carried documents proving their status as free women, they were nevertheless captured by agents of enslavers to be returned to the South under the Fugitive Slave Act. The case was heard in court two days later. Apparently after a prearranged signal, the crowd surged up and bustled the two women out past their captors and to safety. You can read a detailed description of this fascinating incident here.

The rescue of Small and Bates was enacted almost entirely by Black men and women, whose quick thinking and literal solidarity won the day. Playing crucial roles were Samuel H. Adams and Samuel Snowden, both African American men, and an African American woman who physically restrained the deputy sheriff. Thankful was also in the courtroom and probably helped to plan the action. Lydia Maria Child, in her obituary of Thankful, included this anecdote from that day:

The agent of the slaveholders standing near Mrs. Southwick, and gazing with astonishment at the empty space, where an instant before the slaves stood, she turned her large gray eyes upon him and said, “Thy prey hath escaped thee.”

Thankful (Hussey) Southwick died in 1867. She was so well-known at the time of her death that none other than William Lloyd Garrison delivered her eulogy. Frederick Douglass would call Thankful and Joseph “two of the noblest people I ever knew.” She had lived long enough to see the end of the Civil War and the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, the first of the Reconstruction Amendments. However, she would undoubtedly agree that the struggle for true equality was and still is far from over.

The pictures in this post are reproduced from the MHS’s fully digitized collection of portraits of American abolitionists, which includes photographs of some of Thankful’s other relatives. The MHS also holds a copy of Sarah H. Southwick’s Reminiscences of Early Anti-Slavery Days, privately printed in 1893, and a manuscript volume of correspondence of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, 1834-1838.

![Abigail Adams Smith, miniature portrait on porcelain tile by an unidentified artist, [18--]](http://www.masshist.org/beehiveblog/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Abigail-Adams-Smith-251x300.jpg)