By Susan Martin, Senior Processing Archivist

A fellow archivist and I often talk about that instinct you develop after working in this field for a few years. I call it the “I think this is a thing” instinct. It happens when you’re working with a manuscript collection and stumble on a passing reference, unfamiliar to you, that seems like it may have some significance not immediately apparent. Maybe it’s a name that sounds vaguely familiar. Maybe it’s just the fact that a particular nondescript item was saved at all that makes you ask yourself, “I wonder what’s so special about this?”

The John Hill Thorndike letterbook contains one such intriguing reference. Thorndike was a Boston businessman and lawyer, and his letterbook contains copies of outgoing correspondence, mostly related to real estate investments, property management, and decedents’ estates. Also included, however, are a few letters of more personal interest.

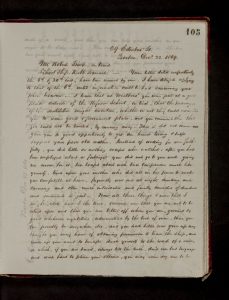

For example, on 22 December 1869, Thorndike wrote to someone named Robert Burk (or possibly Burke) on the school ship R. M. Barnard:

I learn that at Westboro’ you were put at a good place outside of the Reform School, on trial, that the managers of the Institution might ascertain, whether or not they could recommend you to some good & permanent place, and you convinced them that you could not be trusted, by running away. This I did not know, and gave you a good opportunity to get an honest living & help support your poor old mother. Instead of working for me faithfully, you did little or nothing except when watched; after you had been employed about a fortnight you did not go to your work, giving no reason for it, but loafed about with bad companions much like yourself, lived upon your mother who did all in her power to make you comfortable at home, frequently was out all night drinking and carousing and often much intoxicated and finally convicted of drunkenness and sentenced to jail.

Now all these things & more that I might state had I the time, convince me that you are not to be relied upon and that you are better off where you are, governed by good wholesome regulations, administered by the best of men, than you can possibly be anywhere else, and you had better now give up any thought you may have of obtaining permission to leave the ship, and make up your mind to hereafter devote yourself to the work of a sailor, in which, if you are honest, always tell the truth, don’t use bad language and work hard to please your Officers, you may some day rise to be mate of a vessel, and then you can help your mother as you ought to be doing now. You ask how your mother is. She has been quite unwell lately & not able to work.

I’d never heard of anything called a “school ship,” so I did some research, and it was definitely “a thing.” School ships like the George M. Barnard (Thorndike got the name wrong) were used by the Nautical Branch of the Massachusetts State Reform School to train so-called “delinquent” boys to be sailors. Burk, apparently a former employee of Thorndike’s, had written asking him to petition for his release from the Barnard, but Thorndike was having none of it.

The State Reform School in Westborough, Mass. was one of the oldest, if not the oldest, publicly funded juvenile reform school in the U.S., although private reformatories had been around for a while. The impetus for the creation of the school ship system in 1859 was a fire at the school, set by one of the boys living there, that destroyed so much of the building that the governor thought it an opportune time to launch (no pun intended) the Nautical Branch.

In 1867, the Nautical Branch broke away from the State Reform School and became an independent institution called the Massachusetts Nautical School. It would operate until 1872.

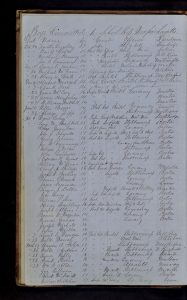

It just so happens that the MHS also holds a volume of records of the first ship used by the Nautical School, the Massachusetts. The Massachusetts was such a success in the eyes of state legislators that they appropriated money for a second and larger ship, the George M. Barnard, named after a major donor.

This volume of Massachusetts records gives us a more detailed look at the boys the state deemed “delinquent.” They ranged in age from 12 to 18. (In fact, younger boys were committed to the Reform School, but the Nautical School was mainly for teenagers.) Their offenses included outright crimes, such as larceny and assault, but also what might be called behavioral problems: stubbornness and idleness, for example. Burk himself had been arrested for drunkenness.

Commitment to these Nautical School ships was a serious matter. Burk would have been sentenced by a judge to work and study on the Barnard until he reached adulthood, or until the trustees considered him reformed and discharged him. If he escaped, he’d be subject to re-arrest by police. He would receive only one family visit every three months.

However, this was an institution aimed at rehabilitation. Its curriculum included not just sailing and navigation, but also making clothes, cooking, and “the ordinary branches of education.” The school received donations from philanthropic individuals and organizations, as well as visits from distinguished guests. Charles Dickens even stopped by the Barnard during his 1867-1868 U.S. tour.

Many of the boys did, in fact, go on to become professional sailors. According to the annual report of the Nautical School trustees, about 40% of the boys committed to the school ships joined “the national, merchant, and whaling service” between 1859 and 1869.

I can’t help wondering about Robert Burk. The Thorndike letterbook doesn’t include any other correspondence from, to, or about him. Neither does the other collection of Thorndike papers here at the MHS. One of these days, I’ll have to stop by the Massachusetts Archives, which holds a collection of case histories of the boys of the George M. Barnard.

That’s a great peace of history my self being a

former merchant marine and living only a few miles from where Mad Jack Percival lived.James H. Ellis wrote a book about him called Mad Jack Percival Legend Of The Old Navy,could not help myself pull it off the shelf as l read your story.He is the first and only one to sail her around the world. Thank you for revealing and sharing that precious peace of History which our nation needs in these last days. Seraphine Rodrigues Sandwich Ma.

lived,while reading your article