By Susan Martin, Senior Processing Archivist

Last year, the MHS acquired a small collection of account books attributed to John Henry Clifford of New Bedford, Mass. Clifford was a lawyer who served in the Massachusetts legislature and as attorney general and governor of Massachusetts. This acquisition supplemented a large collection of Clifford’s papers that we already held.

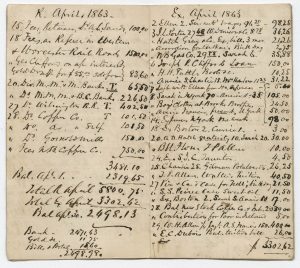

But when I started to catalog the collection, I noticed something odd. Six of the seven account books are tiny booklets measuring about 2 x 3.5 inches with accounts written out in a neat list, “receipts” on the left and “expenditures” on the right. These booklets date from 1847 to 1873.

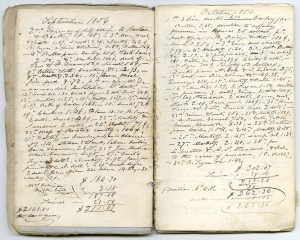

The seventh account book, however, is kind of an ugly duckling. It’s much larger (5 x 8 inches) and consists of hand-sewn signatures of mismatched paper containing miscellaneous accounts from 1845 to 1865. Not only is the handwriting different, but the accounts all run together in one big block of text.

The account books were clearly kept by two different people. The six small volumes are definitely Clifford’s (I confirmed this by checking his papers for a handwriting sample), but who kept the seventh?

It seemed logical to assume the volume belonged to another member of the family, perhaps his wife Frances, and had been misattributed to John. This frequently happens with unsigned manuscripts in collections of family papers. But a closer reading revealed the accounts were definitely kept by a man. Included are records of joint expenses for him “& wife.” And when I compared entries for specific dates to those in Clifford’s, the accounts didn’t correspond. Sometimes our unknown individual was traveling to New York when Clifford was still in New Bedford.

A brother or son, then? Well, the handwriting didn’t match that of any other family member represented in the Clifford papers. So I abandoned that theory and started from scratch, digging into the content for clues.

This was easier said than done. Brief entries listing groceries and sundries purchased don’t exactly give you a lot of biographical details to latch onto. New Bedford is mentioned a few times, which probably explains the original misidentification. There are a few personal names, like Franklin, Sarah, and Dorah, but it was impossible to tell who was a family member and who was, say, a servant. I also saw the name Delano in several places.

Eventually a little more personal information emerged, like “my son Edward” and “my son Warren.” In fact, Warren makes many appearances throughout the volume. Well, John H. Clifford did have a son named Edward, but no Warren. Then I stumbled onto an unfamiliar proper noun that unlocked the whole mystery—Algonac.

If you’re an archivist or historian with expertise in a certain family, you may be ahead of me here. A quick online search revealed that Algonac was the home built by Warren Delano, Jr. in Newburgh, New York. This account book was kept, therefore, by none other than Warren Delano, Sr., who often traveled to visit his son and family. The clincher was the note Delano, Sr. wrote proudly marking his granddaughter Annie’s birthday.

Warren Delano, Sr. lived in Fairhaven, Mass., just across the Acushnet River from New Bedford. He died in 1866. He also happened to be the great-grandfather of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

If I were to extend my earlier metaphor, I’d say the ugly duckling turned out to be a swan. John H. Clifford was a conservative Whig who opposed the abolition movement and was called “pro-slavery” by his one-time servant Frederick Douglass. Warren Delano, on the other hand, supported abolition, aided those seeking freedom from enslavement, and subscribed to anti-slavery publications. Here are some of the relevant entries in his account book:

[27 August 1853] Donation to a Mother, to aid the redemption of a daughter, from the hands of a man thief 2 dolls.

[1 October 1856] Donation to suffering freemen in Kansas 25 dollars

[28 October 1856] For Liberator & A. S. [Anti-Slavery] Standard, & Bal. to the cause of freedom 10 dolls.