By Evan Turiano, The Graduate Center, City University of New York, MHS African American Studies Research Fellow

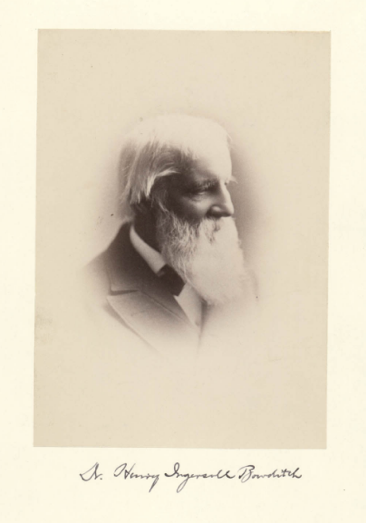

The activists and politicians who made up the Boston Vigilance Committee—an interracial organization committed to securing protection and legal aid for fugitives from slavery—appeared confident in their work. After a man named Joe, who escaped slavery by stowing aboard a ship from New Orleans, was discovered in South Boston and forcibly returned to slavery, Henry Ingersoll Bowditch welcomed movement leaders including Samuel Gridley Howe, John A. Andrew, and Elizur Wright to his home for a discussion of how to mobilize the public outcry over Joe’s re-enslavement most effectively.[1]

They called a public meeting at Faneuil Hall, over which the infirmed former president John Quincy Adams presided, and from that meeting mobilized Boston’s Black and white abolitionist leaders to provide legal aid to accused fugitives from slavery and to petition the Massachusetts legislature for stronger protections against rendition and kidnapping. It was, according to historian Manisha Sinha, an example of how “fugitive slaves fostered abolitionist organization.”[2] Boston would play host to many of the most dramatic, high-profile battles over fugitive slave rendition in the 1850s, events that radicalized the northern public and painted a picture of abolitionist hostility for southern slaveholders. From a twenty-first century perspective, it is easy to imagine this Boston abolitionist vanguard as ready for anything the struggle could bring, war included.

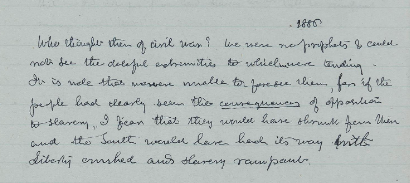

When Henry Ingersoll Bowditch revisited his records of the Faneuil Hall meeting and the movement it precipitated forty years later, in 1886 at the age of 77, he viewed those fights of his (relative) youth differently. In the margins, below the meeting minutes, he scribbled a note: “Who thought then of civil war? We were no prophets & could not see the doleful extremities to which we were tending.”[3] In the fall of 1846, for context, David Wilmot had just introduced his antislavery proviso for new lands claimed in the ongoing war with Mexico to be free of slavery, a proposal that would demonstrate the feebleness of the second party system in face of sectional discord.

Looking back, Bowditch knew the landscape of the struggle over the status of accused fugitive slaves and the future of American slavery, had a long way to go in the next 14 years. The 1850 Fugitive Slave Law would change things dramatically. While the fugitive slave crisis of the 1850s may have rendered war evident to some, it clearly was not so for those activists in 1846.

And yet, in the face of all that unfolded in the two decades following the formation of the Boston Anti-Man-Hunting League, Bowditch did not express regret. Instead, he was glad that their resistance unfolded without any clarity about impending war. “It is well we were not able to foresee this,” he wrote, “for if the people had clearly seen the consequences of opposition to slavery, I fear that they would have shrunk from view.” Southerners, the author knew, would not have shrunk—“The South would have had its way, with liberty crushed and slavery rampant.”[4]

This last clause of the 1886 marginalia is telling. Even when Bowditch feared that knowledge of war would have softened northern resolve and led the antislavery masses toward acquiescence, he knew what most northerners knew before the war: that the proslavery elements that guided southern politics would not flinch at the threat of war. The North had balked first in 1820, again in 1850, and, as Kenneth Stampp showed some seventy years ago, were by and large unwilling to fold again.[5]

So yes, as Bowditch looked back on a nation turned upside down by a war that had cost hundreds of thousands of lives, those years of struggle on behalf of freedom seekers must have looked naïve and short-sighted. Recollection of the past is often inflected with the profound knowledge of one’s prior ignorance. But Bowditch and his colleagues were, in many ways, more steeled for war than he knew in 1846 or in 1886. Decades of struggle had prepared them well.

[1] Sinha, The Slave’s Cause: A History pf Abolition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016) 391-393.

[2] Sinha, The Slave’s Cause, 393.

[3] Boston Anti-Man-Hunting League Records, Box 1, Folder 9, Vol. 9, Vigilance Committee, 1846-1847, Massachusetts Historical Society, p.7

[4] Boston Anti-Man-Hunting League Records, Box 1, Folder 9, Vol. 9, Vigilance Committee, 1846-1847, Massachusetts Historical Society, p.7

[5] Kenneth M. Stampp, And the War Came: The North and the Secession Crisis, 1860-1861 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1950)