By Viv Williams, Processing Assistant and Library Assistant

In preparation for spooky season, I decided to pick up Stephen King’s infamous It. This 1100 page tome (45 hours in audiobook format, in case you were curious) and its 1990s television miniseries adaptation are largely credited in the U.S. for sparking many people’s fear of clowns or coulrophobia.

[There be spoilers ahead.]

In the novel, Pennywise the dancing clown is the most common and recognizable appearance of It–story’s star monster. Pennywise is described as, “wearing a baggy silk suit with great big orange buttons. A bright tie, electric-blue, flopped down his front, and on his hands were big white gloves, like the kind Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck always wore.” He has a white face and a bald head, with tufts of orange hair on either side of his head and a large red clown smile. King actually compares Pennywise to Ronald McDonald within the text of the book.

It claims to favor the form of Pennywise because “small children love clowns.” Having grown up in the post-It world, this baffles me. I don’t actually know what it’s like to NOT find the characteristics of a typical clown innately menacing, Ronald McDonald comparison or no.

The protagonists of the novel find several old photos of It appearing as different versions of Pennywise. The earliest photo, dated vaguely as the early 1700s, pictures a bare-bones street-performing Pennywise with juggling pins and the distinguishable bald head with tufts of hair to either side. It lacks the white face makeup, though the narrator mentions It’s face still looks painted on. It is not until 1850 that the Pennywise persona takes on the full effects of the previous quintessential Ronald McDonald-like clown description. This sent me down a curious rabbit-hole regarding the history and representations of clowns.

Precursors to the clown can be found as early as early back as Ancient Greece under names like Buffoon, Jester, or –most highly esteemed– the Harlequin. They get their start in early theatre, cast as the comic relief or butt of the joke. However, with the rise of the Harlequin in the 16th century, this poor, overly abused character gets retribution and takes on the role of the trickster in later theatrical writings.

The original Grecian buffoon was often recognized by his bald head and padded clothing. Medieval minstrels and court jesters would be distinguished by the “fool’s hat”: a hat with three points that end with jingling bells. The trickster Harlequin of the 16th century would don a thin black mask (much like Zorro’s or Robin’s masks) and often a bat– for mischief, of course. However, from what I can tell, as far back as the 17th century the most common characteristics of the clown included the bald head, white face makeup, oversized shoes, hats, and that classic ruff that even Pennywise eventually sports. So, not much has changed since then.

Encyclopedia Britannica credits Joseph Grimaldi for being the first “true” circus clown appearing in 1805– in England at that. The first mention of circus clowns in the U.S. I’ve been able to track down dates from the 1860s.

As for the MHS collections, most of our clown-esque depictions exist in the form of political cartoons. If you’ve been following any of our exhibition content for the past year or so, this news will find you humorously unshocked and unmoved.

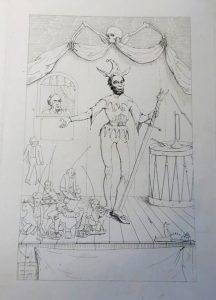

This 1860s John Volck cartoon titled [Jester Lincoln and his puppets] depicts Abraham Lincoln as a jester taking part in a puppet show. Note the aforementioned fool’s hat. The staff or “bauble” as it would have been called was also a common effect of the jester.

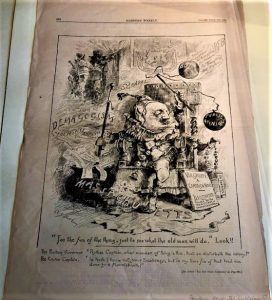

Additionally, this slightly more disturbing 1883 Charles Bush cartoon depicts Benjamin F. Butler as a jester sitting on a throne, stirring a cauldron of numerous negative qualities. This jester was robbed of a few hat points, but has no shortage of jingling bells–I’m sure there’s some significance there, but I’m here to talk about clowns, so I’ll leave that bit to you– and what he lacks in pointy hat, he makes up for in frilly ruff! He seems to be up to mischief so perhaps he is in metamorphosis on his way to Harlequin-hood.

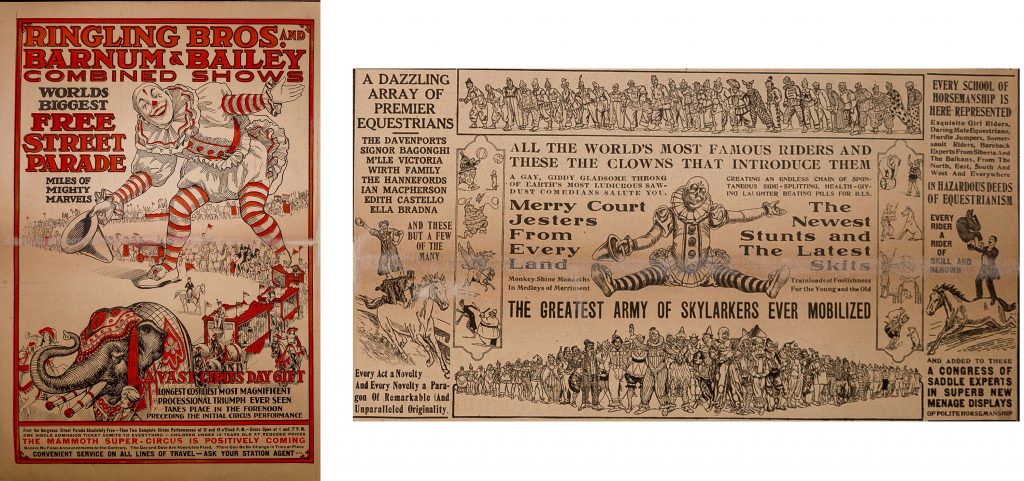

While the MHS collection may not be spilling over with scrapbooks of clown photography, we do have quite the array of traveling circus broadsides from the late 1800s featuring famous names like P.T. Barnum and the Ringling Bros. Unfortunately, only the more recent publications include actual clown illustrations. Here are a few snippets from a delightful 1919 newspaper advertising a combined show between the Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey.

You will immediately notice the similarities between these depictions and Pennywise. The Ringling circus clowns wear masks that mimic the white face makeup and wide red smile. Their silk suits are complete with large red buttons and thick neck ruff, and considering this color image is from the front page of a four page newspaper advertisement spread, we are clearly meant to perceive the figure as inviting and exciting. The black and white photo depicts clowns waving in a crowd of other circus performers– a clear indication that in 1919 these characteristics hold no menacing connotations to a general public.

Today, clown horror is so prevalent that it has arguably become its own subgenre throughout multiple artistic mediums. How do you feel about clowns? Do you want a balloon?

If you are interested in seeing more clown or circus related collections, check out our online catalog, ABIGAIL!