By Heather Rockwood, Communications Associate

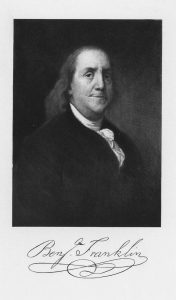

I grew up in Franklin, MA so I always knew the true legend about how in 1778, the town changed the name from Exeter to Franklin, in honor of Benjamin Franklin, in the hopes that he would donate a bell for the church. He never donated money, but sent books instead, which the town debated how to use. In the end, they formed a library where every member of the town could read equally. This started the first public library in the United States. Those books still reside in the Franklin Public Library today. And I know that Benjamin Franklin spent time in Boston during his youth, but I had no idea how often his name would come up while searching the online collections of the MHS. I’d like to share with you a selection of my favorite items and stories I have come across about Benjamin Franklin.

Franklin was born in Boston in 1706 and lived there until 1723 when he ran away from his apprenticeship with his brother, James, who was a printer, to Philadelphia. He only had two years of formal schooling, attending what is now Boston Latin; however he was a voracious reader and even became a vegetarian to spend less money on food and more on books! While he was apprenticed with his brother, James started The New England Courant, the third newspaper created in Boston, which featured literature, opinions, and humor. Franklin knew his brother would not take him seriously if he offered to write something for The New England Courant and so wrote under a pseudonym, “Silence Dogood,” a woman who had opinions. He slipped the first story under the door of the print shop and it was printed in the paper. In all, 13 essays from Silence Dogood were printed in The New England Courant ranging in topic from a dramatic story of her birth, to her opinion on the vice of drunkenness.

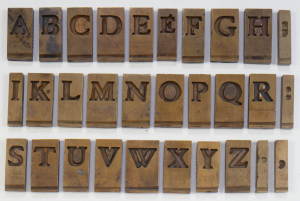

After landing in Philadelphia, Franklin relied on his skills in printing throughout his life. After travelling to London, England and being stranded without funds, he was hired there for his printing skills. He earned a loan to return to Philadelphia, worked off his loan, and began to have great success in his own printing endeavors. He created the first franchise in America by opening a print shop with a partner in another colony; became the official government printer of Pennsylvania, purchased the Pennsylvania Gazette; published the first Poor Richard’s Almanack, an instant bestseller; was appointed clerk of the Pennsylvania Assembly; organized the Union Fire Company of Philadelphia which endorsed fire safety in the city; was appointed Postmaster of Philadelphia; and became the official printer for New Jersey. During that time, he purchased brass matrices in France, which the MHS now holds! He used these in his print shop and later passed them down to his grandson.

During his successful print shop endeavors and after, Franklin entertained his interest in electricity and began conducting experiments. The most famous experiment is the one in which he placed a key on the string of kite and flew it during a thunderstorm. When the kite was struck with lightening, it demonstrated the connection between electricity and lightening. However, a story I “discovered” in the MHS collections is in a letter from Franklin to his brother, John, in Boston. As part of his electrical experiments, Franklin was attempting to electrocute a turkey. The experiment went awry and he electrocuted himself instead! In the 25 December 1750 letter he writes:

“I have lately made an Experiment in Electricity that I desire never to repeat. Two nights ago being about to kill a Turkey by the Shock from two large Glass Jarrs containing as much electrical fire as forty common Phials, I inadvertently took the whole thro’ my own Arms and Body.”

The best part of this story, for me, is that he asks that John tell only one mutual friend who is also interested in electricity, as a warning. “You may Communicate this to Mr. Bowdoin As A Caution to him, but do not make it more Publick, for I am Ashamed to have been Guilty of so Notorious a Blunder.” But letters at the time would be passed around to friends and family and read aloud as a leisure time activity. I wonder if John did keep it to himself, or like me, would have run to his social media of the time, evening letter reading?

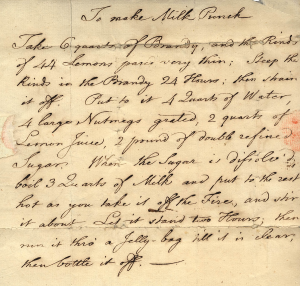

It is during and after this time that Franklin retired from printing and became more involved with politics. When he was as young as 15 years old he divided his leisure time between reading and occupying coffee houses. Coffee houses at the time were more like taverns. You could get a meal and a low alcohol beverage, such as cider or small beer, as well as tea or coffee, and men would congregate there to talk about the news of the day and relax. He liked to chat and because of his humble workman upbringing, he was very comfortable chatting with the lower classes. Due to his intelligence and well-read nature, was equally as comfortable chatting with the upper classes and eventually, the nobility and crowned heads of Europe. Through this practice, Franklin became well-connected in Philadelphia and regarded for his intellect. In 1753, he was elected to the Pennsylvania Assembly. He had been a clerk since 1736 and was tired of listening to debates he could not join. In 1764, he lost his seat after petitioning for a Royal Governor for Pennsylvania, something most people in the colony did not desire. That year he was elected as a colonial agent to England and lived there for over a decade, eventually becoming a representative of Georgia, New Jersey, and Massachusetts. During his time in England, Franklin gained an honorary doctorate from Oxford University and was there after called Dr. Franklin. After five years in England, Franklin came back to the colonies. Travelling through Boston, on 11 October 1763 he wrote a letter to James Bowdoin, the same friend to whom he cautioned about electricity in his letter to John. In this letter, he gives a recipe for a drink that seems vile to me, milk punch. It is a drink that crosses milk, a base, with lemon juice, an acid, therefore curdling the milk on purpose. The curdled milk is eaten with a spoon and the rest is drunk as is, or drunk from a special spouted cup to drink the liquid first, and eat the curds later. Through the years, MHS staff members have attempted to make Franklin’s milk punch recipe. Read about one such account here.

After he returned from England in 1775, Franklin was committed to the cause of Independence. He was elected as a Pennsylvania delegate to the Second Continental Congress, Postmaster General of the Colonies, and in 1776 was appointed as part of the committee of five who drafted the Declaration of Independence. He was then appointed to the French court as one of the commissioners of the Continental Congress and spent the next nine years in France creating an alliance with the King of France and signing the Treaty of Paris which ended the Revolutionary War. In the next five years he invented bifocal glasses, returned to the US, was elected President of the Pennsylvania Executive Council, signed the US Constitution, and submitted the first antislavery petition before the US Congress.

In a 12 May 1784 letter to Samuel Mather, son of Cotton Mather, Franklin describes his birthplace of Boston with nostalgia, knowing he would never visit again:

“I long much to See again my native Place, and once hoped to lay my Bones there. I left it in 1723; I visited it in 1733, 1743, 1753, & 1763. In 1773 I was in England; in 1775 I had a Sight of it, but could not enter, it being in Possession of the Enemy. I did hope to have been there in 1783, but could not obtain my Dismission from this Employment here. And now I fear I shall never have that Happiness. My best Wishes however attend my dear Country, Esto perpetua. It is now blest with an excellent Constitution. May it last forever.”

His fear became reality as he died in 1790 of a life-long ailment of pleurisy. He is buried in Philadelphia.