By Susan Martin, Senior Processing Archivist

The MHS holds the papers of some of the most preeminent people in Massachusetts and U.S. history, including presidents, governors, senators, ambassadors, business leaders, you name it. What about the less privileged and well-connected? They tend to leave a smaller documentary footprint, but their papers can also be found in our stacks. One of my favorites is the 1878 diary of an anonymous itinerant laborer.

The small leather-bound volume is well-preserved and the writing very neat, with no deletions or insertions, so it may be a manuscript copy, rather than the original. The name Charles A. Clifford of Lowell, Mass. is inscribed inside the front cover, and his handwriting matches the writing inside. Clifford’s calling card, printed with an address in Lawrence, is also enclosed. I located an attorney in Lowell and Lawrence by that name, but he wasn’t born until 1883. If my identification is correct, this volume is an early 20th-century copy made by Clifford, but I can’t be definitive.

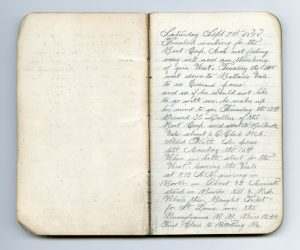

Whoever the author, the content is fascinating. The diary begins:

Saturday Sept 7th 1878 Finished working for the Boot Corp. Am not feeling veary well and am thinking of goin West. Tuesday the 10th went down to Ballards Vale. to see Edward Jones. and see if he would not like to go with me. he makes up his mind to go.

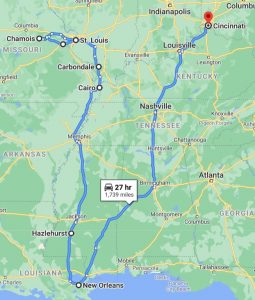

The “Boot Corp.” was the Boott Cotton Mills in Lowell. Our diarist left Lowell with Edward Jones and from there headed west and south in search of work, never staying very long in one place. I did my best to map his route, which included legs by train, steamboat, and on foot. He went to Ballardvale, Mass.; Boston; Fall River, Mass.; New York; Philadelphia; Pittsburgh; Indianapolis; St. Louis; Pacific, Mo.; Chamois, Mo.; St. Louis again; Carbondale, Ill.; Cairo, Ill.; Hazlehurst, Miss.; New Orleans; and Cincinnati.

He began his trip with $35 in his pocket, the remainder of his pay from the Boott Mills, and he carefully documented all his wages and expenses. Two undershirts: 50 cents. Two pairs of drawers: 50 cents. Use of the Union Depot washroom in St. Louis: 10 cents. Bribing a train brakeman for a ride: 50 cents.

All these specific details combine to create a vivid picture of his experiences. For example, outside St. Louis, he described roads so muddy that he collected 3 to 4 pounds of mud on his shoes as he walked, “and one also slips back every step of 3 feet about 18 inches makeing progress very slow and tiresone.”

Of course, he had to be careful with his belongings. One day, he and Jones dropped their blankets into a wet ditch. Soon after that, when boarding a train, Jones nearly lost another precious possession, his revolver. I’ll quote this passage in full to give you a sense of how the diary is written.

Ed droped the revolver juest as the train was starting and we both had to jump of to finde it. which cheated us out of 11 Miles we had paid for. and which took us till noon to walk. this was the day that Ed was bit by the Bloodhound. we tried very hard to get work at Chemois cuting corn. but did not succead and as we could get nothing to do or eat. we thought we might as well set our faces toward the riseing Sun Again so we do so at 3 P.M. but we do it with A sad hart sore feet and poor Courage. we walk about 3 or 4 Miles which seams like 10 to us and then cross the Misouri which cost us 10 Cts

Our writer had apparently lived this nomadic life for some time. He’d once worked at the West End Hotel in Philadelphia. He was obviously resourceful, but he also got help on more than one occasion from a “kind harted and whole soled” stranger who cut him a break or referred him for a job.

In the diary, he described what sounds like a nearly idyllic three months (at least by comparison) working on the farm of a Mr. Samuel Reed in Carbondale, Ill. He made 13 dollars a month for a variety of chores, including planting—“I dug the first sweet potatoes I ever saw growing”—milking cows, and tending horses. He had a room of his own “which was carpeted and had A good Soft Bed,” and his washing and mending was done for him.

But that job ended, and after he restocked with supplies in preparation for another stretch of unemployment, he was left with 20 cents to his name. His life remained precarious. And having parted with Jones when he took the job at Reed’s farm, he was also lonely.

As it was Christmas Eve. I thought of home. and where I was One Year Ago. […] not A friend on earth that had any Ida where I am. with no money or work and the City full of tramps and men in search of work. what am I to do. Well God knows and time will tell.

But he proved his resourcefulness again when he heard about work in Cincinnati. With no money for the steamship, he secured a spot by leaving his watch and chain on deposit with a clerk, to be redeemed when he received his pay. The descriptions of his hunger and desperation during this part of the journey are some of the most moving passages in the diary.

I thought I could and would wait 1 or 2 days before telling them I was hungry as I was affraid they would not take me any way if they thought they had got to feed me. on the way. […] my guts felt as though they wer all stuck to geather with muserlage. and the Potatoes meat & Grits I receaved that night with coffee with out milk or sugar […] was one of the best if not the best meal I ever Eat. […] hear and now is what I call hard times & rufing of it

He and the other workers slept on deck, leaning against bales of cotton and frequently waking up from the cold.

by the by I find A man can sleep any where after he gets used to it. the sweetest sleep I ever had I had on this boat. & the plesantest dreams I have woke out of dreams that wer like half-hours. spent in heaven. to finde my body so cold that I could scercely walk to the deck stove. to warm me. […] one can not realize it till they experance it.

The diary ends abruptly on this Mississippi River steamboat somewhere north of Memphis. I doubt we’ll ever know any more about the man whose experiences are recorded in this diary, but whoever he was, he has left us a valuable historical record.