By Matthew Ahern, Library Assistant

Jennison v. Caldwell (1783) is one of the most significant court cases in Massachusetts’s history, and a landmark moment in the early abolitionist movement of the fledgling United States. It was the result of six related legal actions that started as an assault & battery case, and ended in a verdict that would prove to be the beginning of the end for slavery in the Bay State. Given our current day understanding of how the judicial system works, we might expect that in the aftermath of this case the practice slavery in Massachusetts would cease immediately. Instead, what occurred was a gradual process of abolition over a little less than a decade, with subsequent freedom suits using Jennison v. Caldwell to argue for emancipation. Why did it happen this way? One answer lies within role of the courts in late eighteenth century America.

First some of the facts: At the center of this case was man named Quock Walker, who had been enslaved at one point by Nathaniel Jennison. Walker had been promised his freedom at a certain age and when that promise was broken, he escaped and found work on John and Seth Caldwell’s nearby farm. Upon learning of Walker’s location, Jennison (along with some friends) severely beat Walker and brought him back to the Jennison farm. Walker managed to alert a justice of the peace however and Jennison was charged with assault & battery. Neither party argued the facts of the attack, and the issue before the court was whether Jennison was within in his rights to do so as Walker’s master. Walker would argue (successfully) that this was an assault & battery, because he was attacked while a free man.

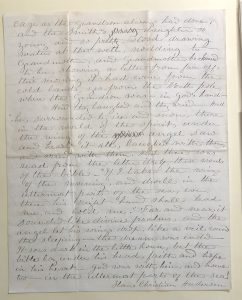

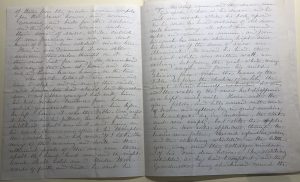

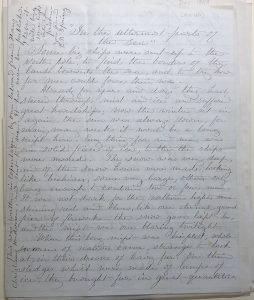

A series of litigation spanning two years would follow, with Jennison’s counsel attempting to legally justify enslavement using Mosaic law, and Walker’s lawyers effectively arguing the untenability of enslavement within the scope of the new state constitution. When this legal battle reached the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts, Chief Justice William Cushing appeared to be convinced by Walker’s arguments. Within his legal notebook, the Chief Justice acknowledged the “Free & Equal” clause of the Massachusetts Constitution, and further writes that, “This being ye Case I think ye Idea of Slavery is inconsistent with our own conduct & Constitution.”

Cushing would conclude by finding Jennison guilty, and Walker’s freedom was ensured. Given that Cushing appeared to base his decision off of the language in the new state constitution, and also that this opinion was coming from the highest court in the land, it only follows that the rest of the state would follow suit and abolish slavery. While eventually this would happen, it was by no means immediate, which may seem foreign to us today given a 21st century understanding of the judiciary’s role.

In recent years, courts, in particular the Supreme Court, have developed the ability to determine what the law is and what it isn’t with increasing authority over their co-branches of government. Judicial review is a powerful tool used by the Court today, and social rights such as abortion and same-sex marriage have been given protections because of it. However, in the legal world of 1783, a judicial opinion would only get you so far. Without legislative and executive support, Cushing’s opinion could serve as persuasive precedent, but it was not the law of the land. This is exactly what would happen, with the Massachusetts General Court remaining silent on the matter, and Governor Hancock himself being unclear regarding the legal status of slavery the same year Jennison v. Caldwell was decided.

Today, Constitutional scholars would say we live in a far more court centric world than ever before, and this is apparent in many ways. It’s the reason the nomination of Supreme Court Justices have become so important (and divisive), or why the Court was able to intervene in Bush v. Gore the way they did. Today the debate centers largely over whether the Supreme Court is the ultimate or exclusive interpreter of the Constitution, but in 1783, Cushing’s Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts was just one of many voices interpreting the new state constitution.

In the end, it seems that even in the face of legislative and executive indecision about abolition, subsequent freedom suits along with growing grassroots support effectively ended the practice of enslavement by 1790. So, while Walker’s freedom suit is not only a critical moment for the abolitionist movement of this country, it also provides some valuable insight into the role of courts during the early days of the republic.

Cushing, John D. “The Cushing Court and the Abolition of Slavery in Massachusetts: More Notes on the “Quock Walker Case”.” The American Journal of Legal History 5, no. 2 (1961): 118-44

Cushing, William. Legal Notes. Massachusetts Historical Society. MHS Collections Online: Legal notes by William Cushing about the Quock Walker case, [1783] (masshist.org)

Murphy, Walter F. American Constitutional Interpretation. Foundation Press. 6th Edition., 2019.