By Susan Martin, Senior Processing Archivist

When the MHS acquired the letters of Augustus Percival, the condition of the collection left a lot to be desired. The letters themselves were presentable enough, at least as presentable as we could reasonably expect 150-year-old documents to be, but the collection was a jumble. Letters were out of order; envelopes were missing; pages were separated, mismatched, or torn at a fold; some appeared to be fragments; and many were undated or partially dated (for example, with just a day of the week). Without better arrangement and description, the collection would be incoherent to researchers.

First, some background: Augustus Percival (1830-1883) was a mariner out of Cape Cod. He engaged in trade with China, Taiwan, South Africa, Cuba, Jamaica, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Singapore, working his way up from first mate to captain of his own ship. From 1868 to 1883, he wrote detailed, multi-page letters to his wife Mercy (Higgins) Percival back in East Orleans, Mass., and these are the letters that make up the collection.

In fact, the letters are really more like a diary. As the days passed, Percival wrote and wrote, adding new pages as needed, until he came to a port or encountered a ship that could deliver the whole bundle back to Massachusetts. So each letter covers multiple dates and locations.

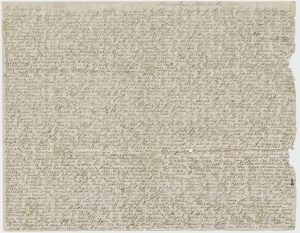

It was my job to catalog the collection, and it was going to take careful reading, content analysis, and physical examination—in other words, a combination of contextual and physical clues—to reassemble the letters and render them useable for researchers. Complicating matters was the sheer density of the material. Most of the letters were written on thin, fragile paper, and Percival made good use of every inch of every page, writing all the way to the edges on both sides.

The MHS holds no other manuscript collections related to Augustus Percival, his family, or any of the ships on which he sailed. Between 1868 and 1883, he traveled on at least five different ships to far-flung locations in Asia, Africa, and the Caribbean. So I started by using the dated letters in the collection to reconstruct his movements.

With a rough timeline of his whereabouts, I could then look at each orphaned page and try to plug it into the narrative based on contextual clues. I could generally tell, for example, if a passage was written at sea or on land. Percival might also mention someone by name who was a crew member of a specific ship or an acquaintance at a specific port.

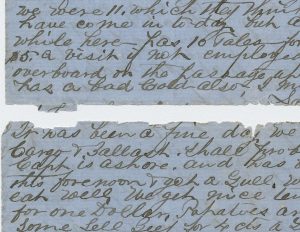

Although he wrote his letters over the course of many days, Percival typically started each new day on a new page. As a result, many pages that looked like they might be the start of a new letter turned out to be subsequent pages of a continuous one. Thankfully, he was assiduous about addressing and signing his correspondence, so if a page didn’t begin with “my dear wife” or end with “your affectionate husband,” it was most likely part of a larger whole.

Percival did number the pages of his letters, but his numbering proved to be unreliable. And even dated entries on the same page were sometimes out of order. For example, in one instance, he left his unfinished letter on the ship, started a new one onshore, then accidentally left that behind and returned to fill in a blank space on the original page. It was only when I wrangled all the individual manuscript pieces together and read through them chronologically that the narrative made sense.

Percival used various types of stationery—folded half-sheets, whole sheets, off-white paper or blue, even green—and different colors of ink. These kinds of physical clues might indicate that two pages belonged together, but then again they might not! When he ran out of supplies, Percival scrounged for whatever was handy. You could say that the physical condition of the collection, as much as the content, reflects Percival’s peripatetic life.

In a few cases, I resorted to using paper folds or rust stains to match sheets together. Based on the folds of two separate pages, I could make a pretty good guess that they’d been sent in the same envelope. If they’d been paper-clipped and that clip had rusted, the stains lined up. Sometimes it came down to piecing fragments together like a jigsaw puzzle.

As you can imagine, this process was painstaking and required a much closer reading of the material than I’m usually able to do. It was ultimately successful, though; I was able to date all the fragments, reassemble all the letters, and fill in the gaps of Percival’s story.

It was also worthwhile because the collection is truly fascinating. Percival describes life as a sailor in more detail than we usually get in a collection like this, including crew politics, customs in various countries, encounters with pirates and missionaries, the Chinese opium trade, South African diamond mining, and much more. One passage about Percival’s fight to protect his ship from armed looters reads like a dime novel. He lived an adventurous life and made some remarkable friends along the way, like Abbie Clifford.

Augustus Percival died on his ship, the Thomas A. Goddard, on 14 Oct. 1883 and was buried at sea. He was survived by his wife Mercy and three children, Mary, Augustus, and George.