By Susan Martin, Senior Processing Archivist

This is the fifth and final installment in a series on the diary of William Logan Rodman at the Massachusetts Historical Society. Click here to read Part I, Part II, Part III, and Part IV.

In the first four installments of this series on the diary of William Logan Rodman of New Bedford, Mass., I covered events between the election of Abraham Lincoln and the early months of the Civil War. Rodman’s diary ends in June 1862, before his war service, but later that year he was commissioned major and then lieutenant colonel of the 38th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment. He was killed at Port Hudson, La. on 27 May 1863.

In this final installment of the series, I’d like to backtrack a little and look in detail at a few other fascinating subjects Rodman mentioned in his diary.

The Margaret Scott Case

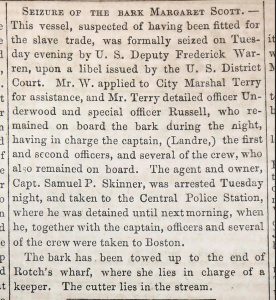

On 15 September 1861, Rodman was summoned before a grand jury to testify in the case of the Margaret Scott, a ship allegedly engaged in the trafficking of enslaved Africans to the U.S. He struck a defensive tone in his diary: “I sold her the water and was an Expert in the water question. My evidence was worth little. I knew nothing about the matter until the water was on board.”

The Margaret Scott had been confiscated at New Bedford a few days before and its captain, officers, and owner arrested. According to newspaper articles published at the time, ships loaded up with excessive amounts of water and dry crackers aroused suspicion, as this was recognized as the fare of enslaved people. Sailors got whiskey and bread.

The owner of the Margaret Scott, Samuel P. Skinner, was convicted and served time in jail, but Abraham Lincoln later pardoned him “on the ground that the party was used by the government as a witness, & testified fairly.” The ship, meanwhile, was sold and used as part of the Stone Fleet, a fleet of old ships filled with stone and sunk in Charleston Harbor in an attempt to block Confederate shipping channels.

Liberia and Haiti

While he waited for his military commission to come through, Rodman kept busy at home. On 10 November 1861, he was elected to the state legislature. One month later, he wrote,

Sent to Mr Eliot a Memorial which I have had numerously signed urging immediate recognition of Liberia and Hayti. […] This would lead to trade. Our City would engage in it and be relieved from the stagnation that now exists & threatens to increase. Africa presents an immense field for commercial enterprise and letting alone the moral effect of our cordially recognizing these Black Republics, too long delayed, our country will reap immense advantage from diplomatic & commercial relations, and no one of our sea ports would be found more fitted for a prosperous intercourse with Africa than New Bedford. We have capital Ships and just the right sort of men, now unemployed.

It’s clear that Rodman’s support for this policy was far from disinterested, but he does briefly reference the “moral” argument. The following year, the United States would, in fact, formally recognize the independence of Haiti and Liberia and establish diplomatic relations with both countries. It had been 58 years since the Haitian Revolution led by Toussaint L’Ouverture and 15 years since Liberia constituted itself a republic.

The Great Charleston Fire

On 11 December 1861, a “fearful” and “terrible” fire ravaged Charleston, S.C. Almost immediately, rumors circulated that the fire had been started by enslaved people. Now, Rodman never made any secret of his particular hatred for South Carolina, given that it had been the first state to secede. He not only found these rumors credible, but he greeted them with overt schadenfreude, calling the fire

[…] a significant symptom. What horrors may yet visit those wicked authors of this our severest trial. […] A year ago our sympathies would have been excited and our purses opened to relieve. Now we are almost pleased and regard it as only one part of the retribution justly due from that center of rebellion.

According to the 2016 annual report of the Charleston Fire Department, the Great Charleston Fire of 1861 was the worst in the city’s history and resulted in $7,000,000 in damage. It swept across the breadth of the peninsula and was witnessed by none other than Robert E. Lee himself. My research indicates that there’s still no consensus on its cause.

As Rodman wrote, “Well we are in the midst of history now with a vengeance.”

William Logan Rodman died at the age of 41, survived by two sisters and several nieces and nephews. According to historian Earl Mulderink, he was “New Bedford’s most prominent casualty during the Civil War” (p. 77). The town’s Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) post and Fort Rodman at Clark’s Point were both named after him.

Select Bibliography

Higginson, Thomas Wentworth. “William Logan Rodman.” Harvard Memorial Biographies, vol. 1, Cambridge, Sever and Francis, 1866, pp. 64-78.

This biography includes excerpts from the diary, as well as Rodman’s later correspondence (which is not held by the MHS).

Jones, Charles Henry. Genealogy of the Rodman family, 1620-1886. Philadelphia, printed by Allen, Lane & Scott, 1886.

Mulderink, Earl F. New Bedford’s Civil War. Fordham University Press, 2012.

Rodman family papers, New Bedford Whaling Museum, New Bedford, Mass.