By LJ Woolcock, Library Assistant

We’re getting close to a year since the pandemic set in here in the US, which I think we can all safely say, no one could have imagined when things first started closing down in 2020. While sourdough definitely stole the show as America’s new hobby, my colleagues and I at the MHS library know there’s also a wave of new historians who have been using their time in quarantine to dive into research. At the same time, most historical institutions, libraries, and archives remain shuttered. As a library assistant, one of the most difficult things I have to do on a regular basis is tell patrons that they’re going to have to wait or request reproductions of the materials they’re interested in using.

So, how can you carry on with historical research when many archival collections are inaccessible and libraries are closed?

I’d like to offer some of the sources that I regularly turn to–both in helping patrons as well as with my own research–when I am not able to access unique archival collections.

Print Materials

Books, pamphlets, advertisements, broadsides, and other printed materials often are unappreciated when it comes to historical research. They’re not given the same value as manuscript collections because they are not unique documents. They also lack the “numen” that archives hold for people: that sense that you’re touching history, making a direct physical connection with the past. However, printed materials contain a wealth of information and ought not to be overlooked.

A fantastic example is city directories. They are incredible tools for identifying regular people living in the city in the past. If you’re looking for someone specific, they list names, addresses, and professions, which you can then use to try to find further sources on an individual. On a broader scale, they also give a bird’s eye view of who was living in the city, where they lived, and what they did for a living. They allow you to form a textual map of a street, neighborhood, or the city as a whole.

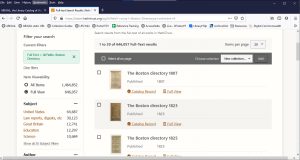

The MHS holds physical copies of Boston city directories from the first publication of the Boston Directory in 1789, into the 20th century:

But many have also been digitized and can be accessed for free on HathiTrust and the Internet Archive.

This is just one example. If a printed book is in the public domain (in general, works published before 1926 or were released more than 95 years ago), there’s a chance that it’s been digitized. For example, if you’re interested in the history of Black activism or Boston’s Black community, David Walker’s Appeal in Four Articles, one of the only published works in U.S. literature to openly encourage to Black people to resist slavery and other forms of white oppression, is available in full on Google Books. Walker self-published his Appeal from Boston’s Beacon Hill neighborhood, and thousands of copies travelled to Black readers across the US.

Working with print materials may not provide the same experience of tracing the pen strokes of the past like archival documents, but it does emphasize how history is something that’s built—that you have to take many scattered pieces to construct an image of what the past looked like.

Published Archival Documents/Edited Editions

Two resources we often use at the MHS are our publications Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society and Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society. These publications, documenting new acquisitions and meetings of the Society, hold unexpected treasures. They’re filled with full transcriptions or edited editions of documents that would be otherwise inaccessible outside of our reading room.

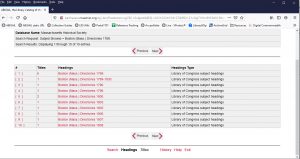

If you find a collection or source in our catalog, check the form “Additional Forms available.” If it has been published in either Collections or Proceedings, it will most likely be indicated there with the series, volume, and page number.

Many collections of archival documents that were edited and published in the 19th century are now in the public domain, and many have been digitized and made available online as well. Some editions that I’ve used during the pandemic include the early colonial Records for the Town of Boston (colorfully titled “Second Report of the Record Commissioners of the City of Boston”—there are many subsequent reports that publish town records into the 18th century), the digitized volumes of Massachusetts Town Vital Records to 1850, and Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors of the Revolutionary War.

Modern edited editions, such as the digital edition of the Adams Papers, are also easily accessible during the pandemic.

Digitized Archival Collections

Of course, these are the current gold of pandemic researchers. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve heard, “If only more had been digitized!”

Many of the MHS’ digitized collections live in our online collection guides. If you see a collection guide with a blue “Digitized Content,” you can click through to see what materials are available online.

Objects, art, and some additional archival sources are accessible through on our online Collection Highlights and Online Resources. There are also digitized collections in more unexpected places; for example, the papers of Mary Hartford, a member of Boston’s free black community in the 18th and 19th centuries, can be found in one of our past digital exhibits, “African Americans and the End of Slavery in Massachusetts,” along with materials from many other collections that otherwise haven’t been digitized.

Consult a Librarian

If you’re not sure where to start or how to identify sources that might speak to a topic, you can always email librarians and archivists to ask for help. The MHS library has its contact information here, including our live chat service.

Keep a “for-later” List

Something that I do while conducting my own research, is to keep a document where I save citations of documents, collections, digital history resources, secondary books, and other things related to my topic that are relevant, along with the place I found them. Anything that you think you may want to remember, or check out in the future related to your research can be thrown inside.

I’ve always found it to be a helpful tool, but during the pandemic it’s been especially essential. If you’re only able to access books from your library using a to-go service, you can look at their footnotes and keep a record of what sources you might want to Google. You never know what might be available online; but even if it’s not possible to access those documents now, you’ll have a record of what you’re interested in and where they are.

Keeping a list also provides you with an intellectual history of your own curiosity: you’ll be able to see what in a particular article sparked your interest, and any new paths you may want to explore. And, I guarantee you—no matter how awesome it sounds right now, you will not remember the name of that collection, or the date of that one letter, later on. I can’t tell you how many times my list has saved me from pandemic brain-fog forgetfulness.

Hopefully this provides some new paths for pandemic historians out there. Suggestions like these may not be able to take the place of archival research, but they do provide us some way into our questions. Limits frustrate us, but they also foster creativity—we learn to think in unexpected ways, and create connection that previously might have gone unexplored.

Works Cited

The David Walker Memorial Project. “David Walker’s Appeal.” David Walker Memorial Project, http://www.davidwalkermemorial.org/appeal (accessed 1 March 2021).