By Sara Martin, Editor in Chief, The Adams Papers

On 8 July 1801 Louisa Catherine Johnson Adams stepped aboard the ship America in Hamburg. She was ill, worried for the son she birthed less than three months earlier, and sailing toward an America she knew only as “the land of my Fathers.” Volumes 15 and 16 of the Adams Family Correspondence, two forthcoming volumes in the Adams Papers series, chronicle the exciting and daunting changes in Louisa’s life during the first decade of the nineteenth century. She met the Adams family in the United States, carved a place for herself and her husband, John Quincy Adams, in Washington society, and most importantly embraced motherhood.

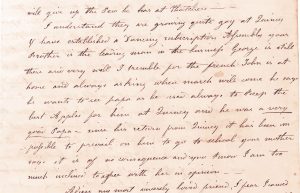

miniature, circa 1792

The daughter of an American father, Joshua Johnson, and English mother, Catherine Nuth Johnson, Louisa was born in London on 12 February 1775. She received her education in France, after her family fled to Nantes during the American Revolution. Returning to London after the war, Joshua Johnson became the U.S. consul at London in 1790, and the Johnson household served as a center for Americans in the British capital. When John Quincy Adams arrived in bustling city in late 1795, he was welcomed into the Johnson home and found the three eldest Johnson “daughters pretty and agreeable.” Louisa captivated his particular focus, and the couple was engaged before John Quincy returned to his diplomatic post at The Hague in late May 1796. More than thirty letters exchanged during their courtship are included in volumes 11 and 12 of the Adams Family Correspondence and are available online through the Adams Papers Digital Edition.

Following the couple’s July 1797 marriage, they moved to Berlin, where John Quincy spent more than three years as the U.S. minister to Prussia. The young diplomat successfully negotiated a new treaty with Prussia but found many of his other duties onerous. Neither he nor Louisa relished the constant whirl of Berlin’s lavish court life, and they escaped the capital when they could, enjoying trips to Dresden and Töplitz and making an extensive tour of Silesia. Louisa’s health in this period was precarious. She experienced several miscarriages before the birth of the couple’s first child, a son named George Washington Adams, in April 1801. “I was a Mother—God had heard my prayer,” Louisa recalled in her autobiography years later.

So it was with a great deal of trepidation that Louisa boarded the America for America in July 1801. After “Sixty long and wearisome days” the family arrived in Philadelphia that September. Louisa spent several weeks visiting her family in Washington, D.C., before traveling to Quincy to meet her in-laws. “Quincy! What shall I say of my impressions of Quincy,” Louisa recalled of her introduction into the Adamses’ community. “Had I steped into Noah’s Ark I do not think I could have been more utterly astonished.” With her cosmopolitan upbringing in Europe, Quincy society seemed foreign. She often felt herself on the outside, looking in.

With John Quincy’s election to the U.S. Senate in 1803, Louisa returned to Washington, a city she found charming on her first arrival in 1801: “I am quite delighted with the situation of this place and I think should it ever be finished it will be one of the most beautiful spots in the world.” The close proximity to her family held great appeal, and she remained in the capital during the 1804 recess, while John Quincy visited his parents in Massachusetts. The situation was reversed in 1806 and 1807, when Louisa stayed in Boston while John Quincy returned to his post in the capital.

Louisa’s frequent letters during these periods of separation discuss a wide range of activities, from what she was reading and who she was visiting to what was going on in Congress and Washington society or locally in Massachusetts. Tender moments between husband and wife are joined by periods of miscommunication and disagreement. But much of Louisa’s letters are filled with commentary about their children, for they welcomed a second son, John Adams, in July 1803, and then another, Charles Francis Adams, in August 1807.

“I feel oppressed with such a heavy weight of care when I look at our lovely children separated as I am from you my life is a scene of continual anxiety,” Louisa wrote on 9 July 1804. “You know how fondly I doat on my Children you may therefore rest assured they shall be watched with the fondest care and every thing that is possible for a mother to do shall be done to promote their welfare during your absence.” Much of Louisa’s anxiety pertained to the children’s health. In a 4 October 1801 letter she noted a “terrible eruption” on George’s skin but was relieved when it “proved to be nothing more than bug bites.” She also commented on common illnesses from teething and seasonal complaints, along with the challenges in getting the children inoculated.

Louisa was delighted—and occasionally exasperated—by her sons’ antics. “George . . . says you are very naughty to go away and leave him he does teaze me so when I write I scarcely know what I am doing,” she wrote on 20 May 1804. And in January 1807 she reported that while John eagerly anticipated the return of his “very good Papa” it had “been impossible to prevail on him to go to school.” George, on the other hand, boasted that he “believed he was too clever” for his schoolmaster.

As the first decade of the nineteenth century drew to a close, Louisa returned to Europe with John Quincy. With her children always centermost in her thoughts, this time she looked longingly back toward Massachusetts, where she left her two oldest children under the care of the Adamses . But that is a story for a later Adams Papers volume.

The Adams Papers editorial project at the Massachusetts Historical Society gratefully acknowledges the generous support of our sponsors. Major funding is provided by the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Historical Publications and Records Commission, and the Packard Humanities Institute. The Florence Gould Foundation and a number of private donors also contribute critical support. All Adams Papers volumes are published by Harvard University Press.