By Rakashi Chand, Senior Library Assistant

With COVID-19 precautions in mind, my husband and I attempted to provide our children with a wholesome school vacation experience by going on a road trip.

We were tested before and after our road trip, wore masks whenever we existed the car, and avoided crowds. We did stop to stay overnight in hotel rooms that we sanitized ourselves with an array of cleaning products packed into the car. We decided this would be the best we could do in the midst of a pandemic. So we drove, and drove, and drove…

Eventually we made it from Boston’s subzero temperatures to northern Florida in what had at times seemed like an impossible mission.

We ended up in the old city of St. Augustine and were pleasantly surprised by the cultural influences that had shaped the small city over the centuries. As we drove, we passed the old Castillo de San Marcos dating from 1672 which proudly boasted to be the oldest masonry fortification in the continental United States. And here, I had to stop. I needed to get out and look at the Castillo.

“Fort Marion,” I uttered as my children and husband watched me walk towards it.

Images flooded my head as I approached the walls of the old fort. This was not a place that I ever thought I would visit. Yet there I was on an unplanned road trip with no destination. Colors, faces, images, and pictographs poignantly came to life in front of me as I thought of a collection housed at the MHS that has always touched my heart, the Book of Sketches Made at Fort Marion, St. Augustine, Fla., 1877.

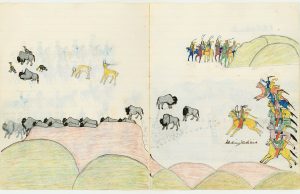

Members of the Cheyenne, Kiowa, Arapaho, and Comanche Nations were imprisoned during the Red River War of 1874-1875 and forced to walk over a thousand miles from their homelands to an internment camp at Fort Marion. There, Lieut. Richard H. Pratt lead an experimental program to force prisoners to ‘integrate’, by dressing them in military uniforms, teaching them to read and write, farm, or do carpentry, and converting them to Christianity. A 24 year-old Cheyenne warrior named Bear’s Heart (“Nockkoist”) was among the prisoners. While at Fort Marion, he became an accomplished artist. The prisoners were given blank books or ledgers, pens, and colored pencils and used this new medium as they would have in the traditional practice of decorating hides with depictions of life on the plains. Often referred to as Ledger Art, the most striking of these drawings is a possible depiction of the Sand Creek Massacre by Bear’s Heart, uniquely portraying the massacre from an Indigenous point of view. His art is beautifully melancholy as it captures and preserves the way of life he left behind. Bear’s Heart documented the prisoners’ long and arduous journey to Florida through his art. After release from Imprisonment, he went on to be a spokesperson for Lieut. Pratt’s education program. Over 100 of Bear Heart’s drawings survive, and the MHS is fortunate to have seven of his pieces. Learn more.

Another name that came to mind was Howling Wolf or Ho-na-nist-to, a Cheyenne warrior who was appointed sergeant of the guards at Fort Marion. When he was released in the spring of 1878, he intended to remain in the east to continue his education but his eyesight was failing. He came to Boston for eye surgery. It was unsuccessful so he rejoined his people on a reservation. There he was struck by the poverty he witnessed. He began speaking out for Indigenous Rights and against the encroachment of Anglo-American culture including the implementation of the Dawes Act in 1887.

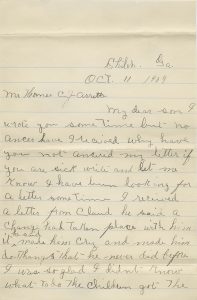

When Howling Wolf left Fort Marion, he drew a pictographic map of his journey from Fort Marion to Savannah, GA and beyond on a postcard that he sent to his father. Both the pictogram postcard and a translation of the pictogram by historian Francis Parkman are in the Book of Sketches Made at Fort Marion. I thought of what it must have meant to finally leave Fort Marion and felt honored that I was going to follow in Howling Wolf’s footsteps (Though I had the unfair advantage of a car!). Luckily, the pictogram had been tucked into the Sketchbook so it could live on.

The art from the sketchbook is a vivid and beautiful memorial to the lives that the artists once lived, before Fort Marion. Hunting Buffalo by Making Medicine is one beautiful example. The collection is fully digitized to explore at home. Within the walls of Fort Marion, many people dreamt of the lives they lived before and through this collection of Sketches we can view some of those moments through their eyes. And, if you are willing to drive, you can even touch the very walls that held so many prisoners surrounded by the beating ocean and wind swept palm trees.

See Howling Wolf’s pictogram to his father Minimic: MHS Collections Online: Howling Wolf’s pictogram to his father Minimic (masshist.org).

See Francis Parkman’s translation of Howling Wolf’s pictogram: MHS Collections Online: Francis Parkman’s translation of Howling Wolf’s pictogram (masshist.org).