By Matthew Ahern, Library Assistant

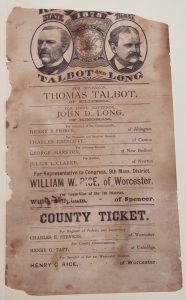

In 1878, the future of the US currency was on the minds of many American citizens. With America in the middle of an economic depression contributing to anxieties around American monetary policies that had existed since the Civil War, the Greenback party had made considerable gains. Greenbackers saw money not restricted by bullion as being inherently helpful to the lower classes during this economic depression, while traditionally minded gold standard supporters feared what Greenback policy would do to the confidence in the American dollar, both domestically and abroad. In 1878, Massachusetts would be confronted by this debate when ardent Greenbacker Benjamin Butler’s was pitted against businessman Thomas Talbot in the gubernatorial election that year. In a contest that mixed personal reputation with monetary policy, it would be Talbot’s “Honest Money, Honest Men”[1] pitch that would win the day.

During the summer of 1878, Civil War General, and disillusioned ex-Republican congressmen, Benjamin F. Butler found himself as the conductor of a populist movement on a Greenback platform that ultimately led to him receiving the Democratic nomination for Governor. Almost as if in response to Butler and his followers, the Republican party nominated the mild-mannered mill owner Thomas Talbot. A former acting Governor of Massachusetts, Talbot supported the gold standard and took a far more moderate stance to both business and labor reform. This election, with these two contrasting figures would be just as much about personality and personal history as it was about policy.

Talbot grew up in poverty, receiving only a partial education, and working primarily as a mill worker when he was younger. Eventually he established the modestly sized Talbot Mills in Billerica and had quickly earned himself a strong reputation paying his employees high wages with fair treatment during a time when mill workers were often treated poorly. By the 1850s, he had entered local Republican politics, and was eventually tapped to be Gov. Washburn’s running-mate in his successful 1874 ticket. Only a few months later, Talbot would find himself serving as the acting Governor after Washburn’s electoral victory for the late Charles Sumner’s seat in the US Senate. Though he was generally well liked during his time in office, Talbot destroyed his chances at winning re-election when he vetoed a liquor reform bill due to his temperance convictions (A stance that would be his political Achilles heel). Still a strong voice in the party, he would need to wait until 1878 to get another shot at the office of Governor.[2]

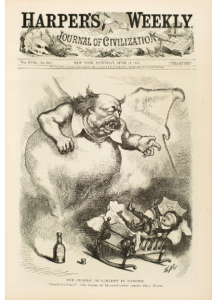

Butler lived a rather different life. Growing up in a family with some means, Butler benefited from an education from Philips Exeter and Colby College. Setting up a legal practice in Lowell, he engaged in speculation and would become a majority stakeholder in the Middlesex Company, a large mill in the city. Entering politics around the same time as Talbot, Butler was originally a Democrat, and first switched party affiliations to the Republican party during the Civil War. As a Major-General for the Union, he was known as an abysmal battlefield commander, but effective administrator. Post-war, he would serve in the US Congress as a Republican, though eventually growing frustrated the Republican platform’s lack of populist policies he had come to favor. Butler switched his party affiliation once more the Greenback Party, and he would carry with him the majority of Democratic party support within the state.

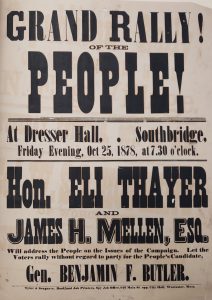

Talbot and his supporters understood that his reputation would be the key to both challenging Butler and adding validity to his more moderate platform. The Talbot Mills had a strong reputation amongst workers, while Butler’s Middlesex Company did not. Talbot was a loyal party-man while Butler had a history of switching affiliations. Talbot also sought no higher office and disliked public ceremony, while many guessed (and rightly so) that Butler, who thrived in the spotlight, would use the Governorship as a step towards the Presidency. Furthermore, he was aided by rising Republican politician Gen. James A. Garfield, who delivered a speech at Faneuil Hall and lampooned Butler’s monetary policy.[3]

Political attacks continued to rage, with Talbot cast as part of the Republican oligarchy currently in power and Butler labeled a demagogue. Despite Butler’s attempts to soften controversial aspects of his history, he was not able to escape the perception of him as a leader of the “Repudiationists, Greenbackers, and Communists” trying to wrestle for power in the state.[4]

In the end, turnout would be massive, with Butler receiving more votes than any other defeated candidate previously, though he was still beaten handily by Talbot 53% to 43%.[5] Voters appeared to have seen the merit in Talbot’s campaign pitch of “Honest Money, Honest Men” over a controversial and radical Butler. Butler would go on to achieve electoral victory in 1882 and launch his bid for the Presidency in his unsuccessful campaign of 1884. As for Talbot, his term in office was characterized by incremental labor and prison reforms, as well as the implementing of the first piece of limited women’s suffrage in the state. Refusing a run for reelection, Talbot became largely a footnote in Massachusetts’s political history, but the campaign he ran in 1878 demonstrated reputation can matter just as much, if not more, than a politician’s policy platform.

[1] “Regular Republican ticket : honest money, honest men.” Rockwell and Churchill, Printer. Boston Athenaeum Collections.

[2] Thomas Talbot: A memorial. Privately printed, 1886. MHS Collections.

[3] Endicott’s letter : Garfield’s speech on honest money : delivered at Faneuil Hall, Boston, Sept. 10, 1878. MHS Collections.

[4] “Address of the Massachusetts Republican State Committee, 1878.” MHS Collections.

[5] “1878 Massachusetts Gubernatorial Election” Congressional Quarterly Guide to U S Elections, second edition.