By Amy Watson, NEH Fellow, University of Alabama at Birmingham

At four o’clock in the morning on 3 July 1745, Boston’s residents awoke to the firing of guns, the beating of drums, and the ringing of bells. The bleary-eyed Bostonians’ alarm soon turned to delight when they learned the cause of the commotion: New England troops had captured the town of Louisbourg, a French colonial port on the island of Île Royale (in what is now Nova Scotia). For the entirety of the day, Bostonians “laid aside all thoughts of business” to celebrate the victory, participating in a city-wide block party that included fireworks, songs, and “plenty of good liquor.” As one eyewitness wrote, “never before, upon any occasion, was observed so universal and unaffected a joy.”[1]

I began my research at the Massachusetts Historical Society with questions about this victory and the celebrations it sparked. Why had New Englanders volunteered to fight the French at Louisbourg? Why were Boston’s residents so thrilled about winning a fishing port on the frigid waters of the Gulf of St. Lawrence? What did they hope to get out of it?

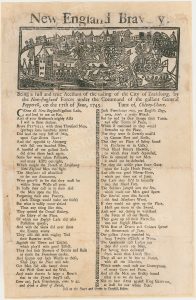

I knew that I would be able to find these answers at the MHS, which has the best collection in America on the Louisbourg expedition, including accounts of military leaders, politicians, and New England soldiers.[2] But my favorite find at the MHS was a simple printed ballad that circulated in Boston immediately following the victory. Entitled “New England Bravery,” this broadsheet describes New England’s capture of Louisbourg in verses to be sung to the tune of the old English song “Chivey Chace.” This ballad gave me not only a glimpse into the raucous celebrations that took place on Boston’s streets in July 1745, but also insight into what Louisbourg represented to the ordinary shopkeepers, merchants, and laborers who sang of its conquest. [Figure 1]

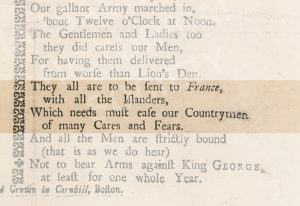

“New England Bravery,” shows the real antipathy that New Englanders held towards their French neighbors in North America. In the ballad’s description of the siege itself, there is the normal lighthearted banter between French and New England soldiers: “Jack Frenchman, cries, you English dogs/ come, here’s a pretty Wench.” But the tone turned serious once the New Englanders successfully captured the port, and decided what to do with their defeated foes: “They all are to be sent to France,/ with all the Islanders,/ Which needs must ease our Countrymen/of many Cares and Fears.” The ballad is therefore advocating for the expulsion of the French-speaking inhabitants of Île Royale, a people whose families had lived in the region for more than a century. [Figure Two]

Why did New Englanders want these French islanders gone so badly? The first motive was commercial: Louisbourg provided access to the cod fisheries of the North Atlantic, a lucrative trade which many Massachusetts colonists hoped to capture for themselves. More pressing, however, were the colonists’ geopolitical concerns. There was a growing political movement on both sides of the British Atlantic in the 1740s to take a more militant stance towards France in order to protect and expand Britain’s imperial hegemony in America.[3] Île Royale was key to this program: British control of Louisbourg could choke off French shipping to Canada, making it too costly for France to continue its colonial operations in the region. As Massachusetts Governor William Shirley wrote, the conquest of Louisbourg was the first, essential step “to drive the French wholly off the North American continent.”[4] The anonymous writer of “New England Bravery” evidently agreed with Shirley’s aims, and many of the ordinary Bostonians who sang the ballad no doubt did as well.

More than a thousand inhabitants of Île Royale would be deported to France in the months following the conquest of Louisbourg, though some would return home briefly in peacetime, only to be expelled again during the Seven Years War. Ultimately, more than ten thousand French-speaking inhabitants of the greater Acadian region would be forced from their homes in the 1750s-60s, a violent undertaking that historian John Mack Faragher has described as an American example of “state-sponsored ethnic cleansing.”[5] Not all New Englanders supported this cruelty. However, “New England Bravery” suggests that in 1745 there were Bostonians in favor of a forced French expulsion singing out in the streets.

[1] Pennsylvania Gazette, 18 July 1745

[2] See William Pepperrell Papers, William Shirley Papers, and William Clarke Journal in Dolbeare Family Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society.

[3] For more on this political movement, see Steve Pincus and Amy Watson, “Patriotism after the Hanoverian Succession,” in The Hanoverian Succession in Great Britain and its Empire, eds. Brent Sirota and Allan MacInnes (Woodbridge, UK: Boydell, 2019), 155-174.

[4] William Shirley to Lords Commissioners of Admiralty, 10 July 1745, The National Archives of the UK, ADM 1-3817

[5] John Mack Faragher, A Great and Noble Scheme (New York: Norton, 2005), 473