By Heather Wilson, Library Assistant

On the evening of her tenth birthday, 22 December 1863, María Teresa Carreño García de Sena (1853-1917), known as Teresa Carreño, sat at the grand piano in the Boston Music Hall. She was ending the year much as she’d begun it–performing for large crowds in Boston. That year she had also played throughout New England, in New York City, at the White House for President Lincoln, and in Havana, Cuba.

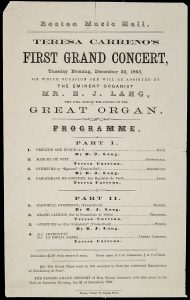

In addition to playing pieces by eminent composers and virtuoso pianists–on this night the concert program shows that she played pieces by American Louis Moreau Gottschalk, and Europeans Franz Liszt and Sigismond Thalburg–Teresa ended the concert with a work of her own composition. La Emilia Danza was a genre of dance music native to her home country of Venezuela, from which she had emigrated to New York with her family in 1862.

I began learning about Teresa Carreño when I read the picture book Dancing Hands: How Teresa Carreño Played the Piano for President Lincoln [1], with my five-year-olds. So, I was excited to spot a record of her in ABIGAIL, the MHS online catalog, as I worked from home on my laptop. After a colleague working in the building emailed me scans of the two items, I showed the photograph to my kids. “Look; this is Teresa Carreño the year she played for President Lincoln! She played for lots of people in Boston, too!”

In fact, she found large and appreciative audiences wherever she went.

On December 19, 1863, The Boston Evening Transcript ran an advertisement for the concert:

Theresa [sic] Carreno, the wonderful little artiste, is announced to give a grand concert at the Music Hall, on Tuesday evening next, the 22d inst. Her visit to Boston last season created unusual interest and excitement in musical circles, and she comes now better fitted than ever to astonish by her truly wonderful powers. She has acquired a greater degree of physical force in the meanwhile, and now performs the most difficult compositions of Liszt, Chopin, Beethoven, Thalberg, and Gottschalk. He [sic] has also composed some beautiful pieces, which will be heard in Boston for the first time. [2]

Many reviewers attributed Carreño’s talent to prodigious abilities and lessons she received from pianists such as Gottschalk, but a fuller picture includes lots and lots of practice at home. Carreño’s father, Manuel Antonio Carreño (1812-1874), played a major role in Teresa’s development as a pianist and composer. Under his tutelage in Caracas, Teresa began studying piano and composing at the age of six. Looking back on her earliest years of lessons, she said she practiced, “two hours in the morning and two in the afternoon, and the rest of the day I played with my doll.” [3] By the time the family emigrated to New York, she had been playing private concerts for years.

Looking at this carte de visite of nine-year-old Teresa, taken in Boston in January 1863, I couldn’t help but wonder what she was thinking. Wearing a dress and earrings, with a stool placed beneath her feet, she strikes a more restful pose than audiences would have seen while she performed. Referring to her ideal style, she once said, “One should be able to play with a glass of water balanced on the wrist.” [4]) Is she thinking about her doll? School lessons? Is she itching to travel back to New York, or eager for spring and her upcoming concerts in Cuba? Does she love to play as much as Dancing Hands suggests?

Indeed, some reviewers were skeptical of Carreño, and child pianists as a whole. The reviewer John Sullivan Dwight attended Carreño’s January 1863 performances in Boston. Although he called her “a wonder” he also wrote:

The danger is lest her talent, by such early continual exhibition and exposure, should all run to waste in superficial, showy music; and no less, that such abnormal and excessive tasking of the brain should wear the life out soon.” [5]

Dwight may not directly call her father a “stage dad” here, but if anyone was responsible for Carreño’s ‘continual exhibition’ it would have been him. In adulthood, however, Teresa Carreño credited her father with seeing her love of piano and teaching her so well:

You see what a foundation I had from my father who, in all his busy life […] found joy in training his little girl in the art which he so dearly loved, and of which he was himself in reality a master. [6]

Later in life, Carreño taught piano in the style her father had taught her as a child. She also continued to perform around the world for more than 50 years.

I was struck by Teresa’s fond memories of learning the piano from her father. Could her story, I asked myself, inspire my own parenting? Eight months into remote PreK (plus two months of summer learning run by yours truly), the only instruments my kids have played have been made out of recycled materials. One of my kids taught himself to whistle(!), but thus far has been unable to teach me to do the same. Perhaps, in the end, it comes down to sharing what you know and love. After all, we’ve read a lot of great historical books. And, besides, they don’t turn six until next year.

¡Feliz Cumpleaños, Teresa Carreño!

Teresa Carreño’s Archive

Teresa Carreño’s records are split between two institutions. The Teresa Carreño Papers, 1862-1991, are housed at Vassar College Archives and Special Collections Library. A digital exhibit provides access to a few primary source materials housed in the collection. (I personally love the 1886 program to a concert she performed in Caracas that refers to her as “al ilustre Americano.”) The Teatro Teresa Carreño in Caracas, Venezuela also houses a large collection of her personal and professional papers and materials, in addition to concert gowns. [7]

[1] Margarita Engle (author) and Rafael López (illustrator), Dancing Hands: How Teresa Carreño Played the Piano for President Lincoln, Simon & Schuster, 2019.

[2] https://documentingcarreno.org/items/show/53, Documenting Teresa Carreño, an open-access website compiling primary source materials related to Carreño’s career, Anna E. Kijas.

[3] Laura Pita, Teresa Carreño’s Early Years in Caracas: Cultural Intersections of Piano Virtuosity, Gender, and Nation-Building in the Nineteenth Century, Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Kentucky, 2019, p. 382.

[4] Pita, 412.

[5] Anna E. Kijas, “The Life of Teresa Carreño (1853-1917): A Venezuelan Prodigy and Acclaimed Artist,” Music Library Association, (Volume 76, No. 1), September 2019, p. 42.

[6] Pita, p. 374.

[7] Ronald D. Patkus, “Musical Migrations: A Case Study of the Teresa Carreño Papers,” RBM: A Journal of Rare Books, Manuscripts, and Cultural Heritage, (Vol 6. No. 1), 2005.