by Susan Martin, Senior Processing Archivist

Tucked away in the stacks of the Massachusetts Historical Society is a small but fascinating collection of letters of the Jarrett family, a Black family living in Shiloh, Georgia. The collection dates from 1905 to 1909 and consists of five letters written to Homer C. Jarrett, who moved frequently but eventually settled in Boston. Each letter contains so many interesting details that I’d like to discuss them individually in a series here at the Beehive.

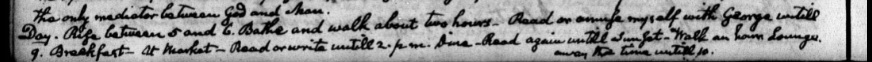

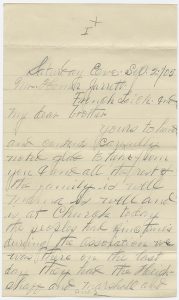

The first letter in the collection was written by Homer’s brother Claud Jarrett at Shiloh. Below is a complete transcription. I will retain misspellings but add sentence and paragraph breaks for readability.

Saturday Eve Sep 2/05

Mr. Homer Jarrett

French Lick, Ind.My dear brother

Yours to hand and contents carefully noted. Glad to hear from you. I and all the rest of the family is well. Mama is well and is at Church today.

The peoples had fine times dureing the Association. We was there on the last day. They had the Heigh-shaff and marshall and three or four depertised White men from Hamilton out there. It was a hundred gal. of whiskey drinked or more and just thousands of peoples were there and not a cross word among them no way. We had one deligate that was Mr. [Elax] Joes of Columbus Ga. the richest negro so said to be in Columbus.

The babe of Wilson that died it was onely 7. seven months old. It was unhealthy and sickely from its birth untill it died. Born Feb. the 11- 1905.

Yes I re’cd the paper you sent me from St. Lewis mo. It was O.K. That train was running sum before it rected. They need not do all that. If I should live and can restore good health I am going to fire the lard out of sume locomotive Engine some day before long.

I have just quit picking cotton. We have out a bale and a half. Sold one bale last saturday at 10 1/8 percts weight even 500 lbs. [illegible] is here now come friday before the third Sunday and is now working with Buck and aunt Sallah. Our little big [hed?] Burt is in Ala. some whare. I re’cd a letter from him the first of the year. He was in Curtisy Ala. I dont know if he is there now or not.

Grandpa and lizzie is well. She is in School now. We have an Independent School now for two 2 months. She is progressing very fast in her studies come home from School ever evening and pick a handle Basket full of cotton. I ben averign too hundred for the last three or four days. It is now field time and I must go.

By by yours brother

Claud Jarrett

The envelope is addressed to Homer at French Lick, Indiana, specifically the “French Lick Hotel D. room,” which probably means Homer worked in the hotel’s dining room. French Lick, known for its sulfur springs, was a newly booming resort town in southern Indiana. In fact, according to census data, the population of the town increased seven-fold between 1900 and 1910, from just 260 people to 1,803.

Sadly but unsurprisingly, it’s been difficult to find a lot of information about the Jarrett family. The matriarch, Julia Jarrett, was born into slavery in the 1850s, and it’s likely many of the people mentioned in this letter were her children. My research indicates she may have had as many as 16. Among them were Homer, born in 1882; Claud, born in 1885; Wilson, the one who lost his child; and Elizabeth, or “Lizzie,” about seven years old when this letter was written.

It’s also been difficult to identify many of Claud’s references. Because the collection contains only five letters, often with large gaps of time in between, I don’t have a lot of context to help. The best I can do is make educated guesses.

First, the Jarretts farmed cotton, so the “Association” was possibly the Southern Cotton Association, an organization established in 1905 to regulate the production (and therefore raise the price) of the cotton crop. The association held state conventions across the South, and it was probably one of these conventions that Claud was describing.

I hoped to identify the man Claud called “the richest negro so said to be” in Columbus, Georgia, delegate to the association, but I’ve hit nothing but dead ends. The name is difficult to discern. I also couldn’t find the newly opened “independent school” Lizzie attended. These two details have been particularly frustrating, but I’ve been in touch with archivists and historians in Georgia and will update the Beehive if I learn anything more. Feel free to leave a comment if you have any leads!

This letter is the only one from Claud in the Jarrett family letters; the other four are from Julia. When he wrote to his brother, Claud was 20 years old and apparently had dreams of becoming a railroad engineer. I like the way he put it: “I am going to fire the lard out of sume locomotive Engine some day before long.”

I hope you’ll come back to the Beehive to read more about the Jarrett family in the coming weeks. If you get a taste for more, the University of Georgia holds a collection of Homer C. Jarrett letters written between 1888 and 1948.