By Dr. Talya Housman, Threadable Books

In 1722, Reverend William Douglass attacked the smallpox inoculation efforts of Cotton Mather and Zabdiel Boylston, dismissing inoculation as based on “a silly Story or familiar Interview and Conversation between two black (Negroe) Gentlemen,” and promoted by “an Army of half a Dozen or half a Score Africans, by others call‟d Negroe Slaves, who tell us now (tho‟ never before) that it is practiced in their own Countery.”[1]

Inoculation had been used in Africa prior to its use in Boston and Mather had heard of the process from Onesimus, who was his slave. Mather defended his and Boylston’s experiments noting that inoculation had worked “upon both Male and Female, both old and young, both Strong and Weak, both White and Black.”[2]

The 1721 controversy over inoculation was not exclusively about race. There were myriad issues mixed up in the debate including medical certification and religion. However, as was the case in much of the eighteenth century American history of infectious disease, race played an important and often times unsavory role.

Human bondage is a critical piece of these stories. Though in this case Mather used his voice to amplify an idea he heard from Onesimus, as Mather’s “property,” Onesimus had little choice in the course of events and we have no record of his voice in the story. Unfortunately, Onesimus is hardly the most exploited enslaved person in the eighteenth century history of infectious disease. Numerous physicians in the Americas performed experiments on slaves. For these experiments, physicians would solicit consent from the owners of slaves, rather than the enslaved persons themselves. Physician John Quier, for example, experimented with innoculation on almost eight hundred slaves.[3]

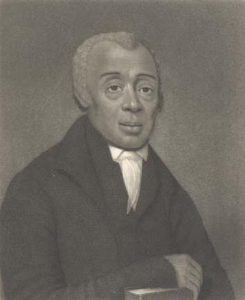

The freed black community was far from unaffected by the interplay between race and infectious disease. In 1793, yellow fever broke out in Philadelphia. Benjamin Rush, signer of the Declaration of Indpendence and one of the most prominent physicians in North America, actively worked to combat the disease. After reading Dr. John Lining’s account of the 1754 yellow fever outbreak in Charleston, Rush wrote to his friend Richard Allen, a preacher and founder of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, who was one of the most influential black leaders of the time.

Yellow fever, Rush informed Allen, “infects white people of all ranks, but passes by persons of your color.” While Rush wrote that this “important exemption which God” granted to the black community from “a dangerous & fatal disorder” did not create “an obligation to offer your services to attend the sick,” Rush emphasized that tending to the sick white community would earn the black community gratefulness. (Interestingly, Rush initially wrote that nursing the sick would “render you acceptable to,” but he struck out those words and replaced them.) Allen and the black community of Philadelphia obliged, tending to the sick white community. However, as Rush himself would later discover, they were no more immune to yellow fever than the white community. [4]

In fact, Lining’s research was part of an ongoing myth that black bodies are more immune to all sorts of things than white bodies: disease, heat, pain – the list goes on.

The intersection between infectious disease and race in the eighteenth century is a reminder that infectious disease intersects with and exposes other existing problems in our society – be they racial, socio-economic, religious, or otherwise.

Dr. Housman’s first book project uses digital tools to explore sexual crime in seventeenth century England. She has written on numerous historical topics including slavery, suffrage, religious freedom, industrialization, charitable giving, and pandemics for various public history organizations.

[1] William Douglass, Inoculation of the Small Pox as Practiced in Boston, Consider‟d in a Letter to A—S– -M.D. & F.R.S (Boston, 1722), 6-7.

[2] Minardi, Margot, “The Boston Inoculation Controversy of 1721-1722: An Incident in the History of Race,” The William and Mary Quarterly, Third Series, 61, no. 1 (2004), 58 citing Cotton Mather, The Angel of Bethesda, ed. Gordon W. Jones (Barre, Mass., 1972), 113.

[3] Londa L Schiebinger, Plants and Empire, (Harvard University Press, 2009). p. 175.

Rana A. Hogarth, Medicalizing Blackness: Making Racial Difference in the Atlantic World, 1780-1840. (University of North Carolina Press, 2017), 220, fn. 12.

[4]Ibid, 24-8.