by Theresa Mitchell , Library Assistant

As someone who is starting her career in the library field, and hoping to start library school in the coming year, I am very interested in how libraries organize information. Paradigms like the Library of Congress Classification not only make the information in our collection easy to navigate, these classification systems are information in-and-of themselves. They trace a lineage of scholars trying to determine the best ways to arrange collections in repositories such as libraries and archives, in accordance with the dominant ideologies of their time.

In the descriptively titled “Four letters to the mayor of Boston regarding waste and inefficiency in the cataloging department of the Boston Public Library” (s.n., 1880), Fredrick B. Perkins penned a series of letters to the mayor of Boston about what he considered to be the malpractice of the cataloging department at the Boston Public Library. His letters, direct and full of wit, call for the mayor to cut the library’s budget as an effort to force them to either decrease staff or decrease the salaries of staff in their cataloging department. He points out some specific examples of their negligence: a card in the card catalogue was labeled “Bomarsund (in India)”, though Bomarsund is in the Balkans (and also a village in the U.K.). Whether or these cataloguers deserved pay cuts and whether or not all Perkins’ claims are true, these series of letters bring up an interesting point: that the navigability of library catalogs is a public concern—even more so now, as public institutions have done more to live up to their mission of serving the public at its broadest.

In the pamphlet “On the construction of catalogues of libraries” (Smithsonian Institution, 1852) written in 1852, prominent librarian Charles C. Jewett—who in his lifetime was the Librarian of the Smithsonian Institution and the Superintendent of the Boston Public Library—proposed a method called stereotyping to effectively create library catalogs.[1] In his program all public libraries interested in adhering to this set of rules would send a formatted list of the titles all the books in their collection. This list would then be made into clay plates for printing. His ultimate hope for this was to create an aggregate catalog of all participating libraries, which would eventually include libraries in Europe, moving toward what he termed a “universal” catalog. Of course, this plan is ideologically limited, the scope of his universalism only extending to the North American and European continents. His vision did not come to fruition, though he remains a figure in the library field for his writing about cataloging methods.[2]

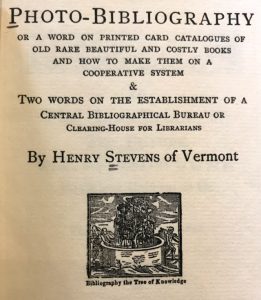

Photo-Bibliography (H. Stevens, 1878), written by bibliographer Henry Stevens in 1878, goes even deeper into the desire for an object that could, in-itself, act as a repository of knowledge. Stevens, an American expatriate living in the United Kingdom, calls for a full bibliography of all English books, and along with this bibliography, a “universal system” for cataloging.[3] To achieve this, he hopes for a “Central Bibliographical Bureau or Clearing House”. He even lays out the ideal dimensions for titles in such a bibliography. Ultimately, though, he does not imagine his vision coming to fruition, because of the ever expanding nature of libraries: “As there is little hope of any library ever even approaching completeness, there is no apparent progress whatever made towards that universal and harmonious catalogue raisonné which we have so long and so devoutly been praying for”. This hope will continue to permeate at least parts of librarianship and academia. Even a resource we have from 1952, “Indexes and Machines,” by the academic librarian Earl Gregg Swem, is intrigued by some way capturing “total-books”, or all the books published in English and European languages.

Looking to create something all-encompassing, these sources point to the limiting viewpoints of their creators, and perhaps more generally, the time in which they were created. None of these sources point to any other epistemologies or consider any sort of relativism, such as forms of knowledge-making outside of the book. Rather, they hint at exceptionalism. Universality came to be a stand-in for all that is a part and product of European and American culture, specifically of the educated classes. The decisions made by those who envisioned a specific classificatory system come to be viewed as neutral and arbitrary. Librarians such as A. Brian Deer have realized the importance of creating classification systems that align with the beliefs of their communities and counter hegemonic classificatory schemes. Deer, a member of the Mohawk of Kahnawá:ke community, created the Brian Deer Classification System in the mid-seventies, which worked to prioritize an Indigenous perspective and an Indigenous audience. This system has been adapted and reinterpreted by various libraries in North America.[4]

Classification systems will never be perfect. Knowing that a total system would at best be a reflection of ideologies of those that created it, the fact no library is “ever even approaching completeness” allows room for growth. As the discourses around knowledge shift to be less conclusive and more inclusive, the ever expanding nature of a collection can come to be less of a burden and more of an opportunity.

If you want to learn more about how we organize our resources, peruse our online catalog, Abigail. And if you are interested in viewing the MHS sources listed in this post, or many of our other resources, please visit our research library, which is free and open to the public!

[1] Baker, B.B. (1993) Cooperative Cataloging: Past, Present, and Future (5). Psychology Press.

[2] Jewett, C. C., & Harris, M. H. (1975). The age of Jewett: Charles Coffin Jewett and American librarianship, 1841-1868. Littleton, Colo: Libraries Unlimited.

[3] Schopieray, C. J. & Hixon, M. Henry Stevens papers (1812-1935). Retrieved from https://quod.lib.umich.edu/c/clementsead/umich-wcl-M-228ste?rgn=Collection+Title;view=text#Additional%20Descriptive%20Data

[4] Doyle, A. M., Lawson, K., & Dupont, S. (2015). Indigenization of knowledge organization at the Xwi7xwa library. Journal of Library and Information Studies, 13(2), 107-134.