By Susan Martin, Processing Archivist & EAD Coordinator

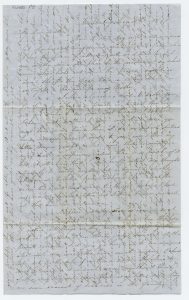

The MHS recently acquired a fascinating letter, dated 10 August 1849 from Mecklenburg County, Virginia. It was written by “Nannie,” a young white woman from New England, to her brother back home. Over four large, densely packed, cross-written pages, she discussed a variety of subjects, including chattel slavery on a plantation in the antebellum South.

It’s a disturbing letter to read. According to Nannie, enslaved people were not mistreated, they suffered more at each other’s hands than at those of enslavers, and Northern opposition to slavery was the real problem, because it made Southerners cling more tightly to their ways. She warned that the South “will see, and vote for, a dissolution of the union before they will give one inch to the north upon the subject.” She also revealed the whites’ widespread fear of revolt and defended the separation of families as necessary to preserve order.

The importance of manuscripts like this to our historical understanding can’t be overstated. Many white Northerners were not, of course, abolitionists, but were either complicit in or openly justified the South’s “peculiar institution.” This letter gives us a first-hand look at their self-serving rationalizations and willful ignorance.

Cataloging this new acquisition was also challenging for another reason: I had no idea who wrote it. Nannie was probably a nickname, but the letter came to the MHS as a single item, not as part of a family collection, so I had no context to help me. I didn’t even know the name of the brother she was writing to. So I began with a close reading of the text, gathering whatever piecemeal clues I could.

- Nannie mentioned several other correspondents, including Elizabeth, Parker, and Caleb.

- She asked about happenings at Amherst, Mass., possibly her hometown.

- She worked as a teacher for a Mr. Pettus, who treated her well and wanted her to stay on.

- She apparently lived and taught in the family home; she described writing the letter “by the windows of my school room which looks out upon the piazza” and going upstairs one night to visit the “boarders.”

- Her brother, the recipient, worked for an abolitionist paper, of which Nannie disapproved.

- She wrote poetry and had previously published her work in newspapers under the pseudonym “Viola.”

And that was it. Not much to go on. I thought my best clue was the name Pettus and started there. Searching online, I found Pettuses galore in Mecklenburg County, including three listed in an 1860 census of enslavers, but I could not pinpoint who employed Nannie. I needed to come at it from a different angle.

I searched using various combinations of keywords (Nannie, Pettus, Mecklenburg, plantation, Parker, Caleb, Amherst, Viola, 1849, etc.), hoping but not expecting to stumble on something helpful. To my surprise, I got a break in the case, so to speak. I found a transcription of an 1851 letter from Arlena Pettus to someone called Nancy “Nannie” Henderson Hubbard!

Arlena had apparently been one of Nancy Hubbard’s students, and the details in her letter matched what I knew—she even asked after her teacher’s birds, and our Nannie had written about keeping mockingbirds. Using this website as a jumping-off point, I set out to confirm the identification. I found Historic Homes of Amherst, a 1905 publication by Alice Morehouse Walker, which filled in most of the gaps: Nancy Henderson Hubbard, born in 1823, attended school in North Amherst, “went South as a teacher,” and published poetry under the pen name “Viola.” This was definitely Nannie.

Researching Nancy Hubbard’s family tree, I found a brother Parker (who incidentally later served in the Union army), a sister Elizabeth, and a brother Caleb. The only living brother she didn’t mention in her 1849 letter—and therefore its recipient—was Stephen Ashley Hubbard (1827-1890), a journalist in Connecticut and later managing editor of the Hartford Courant.

Arlena’s letter not only linked the names Pettus and Hubbard, but also provided the specific Pettus for whom Nannie worked, the picturesquely named Musgrove Lamb Pettus (1808-1881). I verified this with the help of the Library of Virginia, which holds a few of Nancy’s letters discussing Musgrove’s family. My final and unexpected discovery was the 1850 Mecklenburg County census, where Nancy’s name is listed alongside Musgrove, Arlena, and other members of the Pettus household.

Nancy Henderson Hubbard returned to Massachusetts in 1851 and married Ansel Wales Kellogg, a banker in Oshkosh, Wisconsin. She died in Wisconsin in 1863, just thirteen days shy of her fortieth birthday. The Oshkosh Public Museum holds a carte-de-visite photograph of Nancy, a.k.a. Nannie, taken in 1855.

Nice sleuthing!