by Christopher F. Minty, Assistant Editor, the Adams Papers

On 10 August 1774 John Adams departed Boston for Philadelphia. He was traveling with Robert Treat Paine, Thomas Cushing, and Samuel Adams. Together, they were Massachusetts’s delegation to the First Continental Congress. It was a long, slow ride. But on the way, they took advantage of the opportunities travel presented. They stopped in villages, towns, and cities on the way. For John Adams, New York City was the most interesting place they visited.

The delegation was in Manhattan from 20 August to 26 August, longer than they stayed in any other place. Upon his arrival, Adams noted in his diary, “This City will be a Subject of much Speculation to me.” And it was. Adams committed eighteen pages of his diary to his time in New York, considerably more than any other place. He noted down who he met and how they came across. He also offered commentary on buildings, streets, dining sets, the weather, and New York’s government.

Adams kept a diary not only for his benefit, though. “I have [kept] a few Minutes by Way of Journal,” he told Abigail Adams on 28 August, in one of the few letters he wrote during this period. The diary, Adams went on, “shall be your Entertainment when I come home.” To make his entries enjoyable, John Adams recorded almost everything he saw and everyone he met. In short, his diary represents a who’s who of eighteenth-century New York City. He met or dined with some of the city’s most prominent men, many of whom shared his radical views about the Continental Congress and the increasingly extractive nature of British imperialism.

When Adams arrived in New York City, his first stop was Hull’s Tavern at 10 A.M. on 20 August, a Saturday. Hull’s Tavern was operated by Robert Hull, and it was located at roughly 115 Broadway, not far north of Trinity Church or far from the Oswego Market. But he didn’t stop for long. After Hull’s Tavern they moved to the home of Tobias Stoutenburgh at King Street (present-day Pine Street) and Nassau Street. It wasn’t far from Hull’s; about a five-minute walk. Stoutenburgh, a goldsmith, owned a large lot, complete with a garden and orchard. During Adams’s time in Stoutenburgh’s house, he met Alexander McDougall and Jeremiah Platt, two politically active New Yorkers who, by this stage in the imperial contest with Britain, were leaders of one of the partisan groups in the city.

The meeting between these New Yorkers and Adams, and the Massachusetts delegation, was an important moment. Platt invited the delegates to dine with him on 22 August. He left shortly thereafter. But McDougall, Adams wrote, “stayed longer, and talk’d a good deal.” “He is a very sensible Man,” Adams continued, “and an open one. He has none of the mean Cunning which disgraces so many of my Country men. He offers to wait on us this afternoon to see the City.”

McDougall took Adams and the other delegates into public places where they might be useful for partisan purposes: taverns, Fort George, the equestrian statue of George III, various partisans’ houses, and “up the broad Way.” Altogether, Adams went to nearly “every Part of the City.” Along the way McDougall introduced him to his like-minded colleagues and friends. During a quiet moment, McDougall gave him a break-down of political affairs in the city, noting that there were “two great Families” in New York “upon whose Motions all their Politicks turn.” The Livingstons, associated with McDougall, held “Virtue and Abilities as well as fortune.” The DeLanceys, Adams was assured, had “not much of either of the three,” whilst McDougall had a “thorough Knowledge of Politicks.”

It wasn’t long until McDougall took Adams to a private residence, a place where they could really chat. On 22 August, Adams was taken to a home on what is now W 43rd Street, between Eighth and Ninth Avenues. There, Adams and McDougall spoke at length about politics, developing an alliance that would continue through the Continental Congress. Of those who “profess attachment to the American Cause,” McDougall recommended Adams “avoid every Expression here.” McDougall, Adams went on, “says there is a powerfull Party here, who are intimidated by Fears of a Civil War, and they have been induced to acquiesce by Assurances that there was no Danger, and that a peacefull Cessation of Commerce would effect Relief.” These people were the DeLanceys, individuals whom Adams and the delegation should avoid.

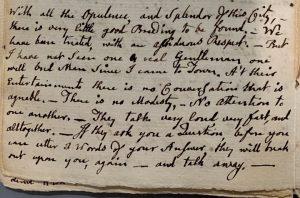

New Yorkers’ eagerness to mobilize John Adams to their cause was obvious, too, at least to him. They recognized his potential influence—and they wanted him to know that they were with him. “At their Entertainments,” Adams famously wrote, “there is no Conversation that is agreable. There is no Modesty—No Attention to one another. They talk very loud, very fast, and altogether. If they ask you a Question, before you can utter 3 Words of your Answer, they will break out upon you, again—and talk away.” These men could not wait to curry favor with Adams.