Ian Saxine, Bridgewater State University, W.B.H. Dowse Short-Term Research Fellow at the MHS

Three years into a costly and unsuccessful war with the Wabanaki Confederacy on their “Eastern Frontier,” in 1725 Massachusetts leaders sent a commission to speak to their Indigenous foes and enquire “what was the Occasion of the war which the English…hardly knew.”[1] Most readers would find it hard to believe this ignorance over the causes of a conflict sparked by Bay Colony leaders’ consistent misreading of Indian treaties was genuine. So did I, when I started research on what will be the first book length treatment of a sprawling regional war between Massachusetts and the Wabanaki Confederacy during the 1720s that threatened to draw in numerous other unwilling colonies and tribes. The conflict went by many names (Dummer’s War, after the acting Massachusetts governor, is the most common), none suitable or often remembered. Marked less by battlefield drama than by small-scale ambushes and endless, fumbling negotiations, the conflict stands out to me for what it reveals about the invisible constraints on imperial ambitions in the early modern world. Most New England colonies agreed with Wabanaki critiques of Massachusetts’ unreasonable conduct towards them, and so refused to aid their beleaguered neighbor.

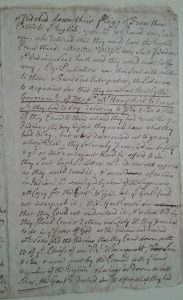

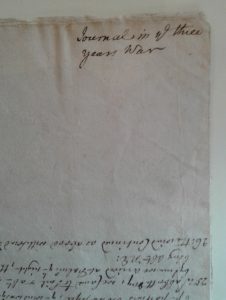

The details of one of the Bay Colony’s ensuing fact-finding missions survives in the MHS collections in a slender, unassuming booklet written by Captain John Penhallow, a militia officer posted on the Maine coast in the summer of 1725. Likely intended for his superiors, Penhallow’s “Journal in the three years War” detailed a month of diplomatic sausage-making. Unlike the better known records of formal treaties that punctuate colonial history, Penhallow’s account is stripped of ceremony. Instead, readers will encounter fumbling efforts to communicate in French, English, and Abenaki, a rare mention of Wabanaki writing symbols (“a few lines in Indian…[colonial translators] Could not interpret” and a detailed description of Indigenous property boundaries, also a rare find in any eighteenth-century collection.

This item, catalogued as the John Penhallow Diary, is an unpolished manuscript, and was perhaps intended as the draft of a more formal report. In that respect the piece represents a way in which MHS collections from this period tend to shine—as an excellent repository of the private writings of public figures, whose official correspondence can be found down the road at the State Archives. John was the son of Samuel Penhallow, a superior court judge and prominent figure in colonial politics who wrote a book about the wars on the Maine frontier in 1726, and this item probably remained in Penhallow family collections before ending up at MHS.[2] (Similar, although much less illuminating reports of less well-connected militia officers can be found in abundance in the State Archives.)

Its unassuming appearance and lack of any headings give no indication that this document contains rare insights into Wabanaki politics and culture. Penhallow recorded candid Wabanaki statements about their land use practices, boundaries between groups, and internal political divides that seldom make it into official accounts of treaties published by Massachusetts.

This manuscript is one of the most powerful examples in my own experience of important findings coming from unexpected places. Penhallow’s account is probably mentioning a form of hieroglyphs used by the Wabanakis’ Mi’kmaq relatives. That, and its equally rare description of Indigenous property boundaries, makes it an invaluable resource for ethnohistorians interested in either of these understudied phenomena.

[1] All quotations from 15 July, 1725 John Penhallow Diary, n.p.

[2] Samuel Penhallow, History of the Wars of New-England. Boston, 1726. 1796 Lib. 31.21