By David Krugler, Professor of History, University of Wisconsin–Platteville

As a historian, I have mixed feelings about historic anniversaries. I welcome the surge of public and press interest in the past that comes with, say, a centennial, but too often, that attention gets compressed into an On this Day in History factoid. Without context and exploration, the meaning and relevance of a historical event can easily be neglected. Another challenge: What if the event being noted isn’t a cause for celebration?

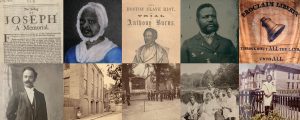

Consider our current year, 2019, which is the 400th anniversary of the landing of the first enslaved Africans in the fledgling colony of Virginia. How should we best commemorate 1619, essentially the birthdate of slavery in English North America? How can 1619, as well as other “nineteens”—1719, 1819, and 1919—be used as lenses to view the history not just of slavery but also that of Africans and African Americans? Last month, I was honored to take part in a four-person panel organized by the Massachusetts Historical Society that explored the legacies of 1619. Appropriately, we convened on Beacon Hill in the chancel of the African Meeting House, the oldest standing African American church in the country. Frederick Douglass once delivered an address from the very spot where we sat, as did abolitionists Sarah Grimke and William Lloyd Garrison. No pressure, right?

We framed our presentations and discussion around the themes of recognition and resilience. To an engaged audience packing the pews of the nave, Peter Wirzbicki, of Princeton University, spoke about the growing awareness in the North by the 1830s of just how much slavery was thriving. Abolitionists in Boston increasingly recognized that slavery wasn’t merely a Southern institution—Massachusetts’s textile industry depended on the price of cotton, which slave labor helped determine. The 1850 Fugitive Slave Act legally bound all citizens to slavery by requiring them, under the penalty of law, to help capture or return runaways (better term: self-emancipators). As Peter put it, “The Civil War had to free the North as well as the South.” That recognition was slow to develop, with even Abraham Lincoln forswearing any intention to abolish slavery when he took the oath of the president.

Kerri Greenidge, of Tufts University, profiled Boston’s own William Monroe Trotter, whose father, born enslaved, fought for the Union. Trotter, an indefatigable activist, showed resilience through his radicalism. Trotter recognized that business as usual, so to speak, wouldn’t dismantle the ideology and structure of white supremacy. In 1902, he mobilized black Bostonians to protest North Carolina’s attempt to extradite Monroe Rogers, a black man who had fled to Boston out of fear of being lynched after being arrested on trumped-up charges. Rogers had to be protected from a corrupt justice system—and then that system had to be reformed. The nation needed a reconfiguration of its laws, argued Trotter, who also called upon African Americans to defend themselves. As Kerri explained, Trotter exemplified a black radical tradition that took root in 1619. For if slavery was normal, then resisting it was, by definition, radical; and if the laws in 1902 didn’t stop lynching, then resisting those unjust laws was also radical.

For my presentation, I spoke about the New Negro movement of the early twentieth century, of which Trotter was a prominent part. (The New Negroes contrasted themselves with the “old guard” represented by the accommodationist approach of Booker T. Washington.) World War I had a profound effect on New Negroes, who recognized that the reason President Woodrow Wilson gave for U.S. entry into that war should be appropriated. If African Americans were going to France to make the world safe for democracy, shouldn’t America be made safe for the rights and equality of African Americans? In 1919, when white mobs formed in city after city to attack African Americans in the cause of protecting white supremacy, black veterans fought back and provided protection that law enforcement failed to offer. A year of racial violence, the worst in the nation’s history, 1919 was also a year of resilience through armed self-defense against lawless mob attacks.

A discussion moderated by Robert Bellinger, of Suffolk University, gave Peter, Kerri, and myself an opportunity to further explore the connections between our respective topics, thus providing the context and analysis that historic commemorations need. So, too, did the audience’s insightful questions, which further enhanced our consideration of recognition and resilience in African American history.

The best part is that the discussion didn’t end with us. On 19 October, the second panel in the series considered the legacies of 1619, this time through the theme of Afro-Native connections. My disappointment at not being able to attend is tempered by knowing that the MHS will soon post a recording of the panel. I look forward to seeing it!

Learn more about the Legacies of 1619 series and watch the first panel discussion Legacies of 1619: Recognition & Resilience.