by Theresa Mitchell, Library Assistant

People were publicly spreading their political ideologies long before the days of social media. For Sarah Winnemucca, a public presence was a key element of her political agenda. Winnemucca, a Northern Paiute woman and daughter of Chief Winnemucca, holds a complex spot in the history of the United States. In part, she took to the written word, publishing a book titled Life Among Piutes: Their Wrongs and Claims, which is in the Society’s collection. The autobiographical work is a deft account of the history of her family and culture, including the agonies of white settlement. Winnemucca was well connected to contemporaries who were engaged in their own campaigns for change. Most notably, she was connected to Horace Mann, his second wife, Mary Peabody Mann, and her sister and fellow education reformer, Elizabeth Peabody. It is through these connections that she was able to share her struggle with a larger audience.

Elizabeth Peabody’s letter to Dr. Lyman Abbot, Sarah Winnemucca’s practical solution of the Indian problem: a letter to Dr. Lyman Abbot of the ’Christian Union, is more of a booklet for a public audience than a letter—it even includes a postscript that refers to itself as a public document—to get support and funding for a school Winnemucca had started for Paiute children in Nevada. In advocating for Winnemucca’s school, Peabody cites Winnemucca’s Christian faith, private (as opposed to communal) land ownership and the fact that the children were to be taught in English as well as Paiute. Winnemucca’s own writing plays into the American rhetoric of creating our own destiny. In an address quoted by Peabody, Winnemucca tells her peers “It will be your fault if [your children] grow up as you have”, saying that “a few years ago you owned this great country; today the white man owns it all and you own nothing.” She was clear that education was the best path forwards for the Paiute and Peabody’s writing gives us some insight into the type of education she offered at the school. There is a subtle impulse towards educational assimilation in the text: Peabody stated that not funding such a school as Winnemucca’s “prevents civilization” among the Paiute “by insulting that creative self-respect and cautious freedom to act.” Indeed, Winnemucca was an activist who felt that she needed to work within the framework of Euro-American systems. In an “Appeal for justice,” a circular in the MHS broadside collection, she states “My work must be done through Congress.”

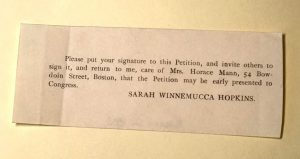

At the same time, she willing to communicate the profound, harmful effect the processes of colonization had on her community. In the early 1880s, the Paiutes were struggling to have reservation lands, acknowledged in the 1860s and subsequently sold off, restored to the community. Winnemucca in particular held this battle for the Malheur Reservation close to her heart. In 1883, the year before Life Among Piutes was published she traveled to Boston where she met the Peabody sisters and Horace Mann. The Peabody sisters were the ones who pushed forward the publishing of her book. During her time in the Eastern United States, she gave public lectures discussing the injustices faced by her people. Her circular “Appeal for justice” mentioned above, was another way a garnering support, and to do so she made her public appeal an emotional one.

In the circular she states, “No door has been open to [the Paiute]; on the contrary, every arm has been raised against them” and that their reservation was “taken from us in the usual way.” In two paragraphs, she establishes her emotional appeal, urging people to seek justice with her. She explains that she is acting not on behalf of herself, but for her people and especially her father. Winnemucca makes her eastern audience aware of their power: “will you give my people a home? Not a place for this year, but a home forever? You can do it. Will you?” It is not until the second and much shorter paragraph that she gives information about the cession Malheur Reservation to the Paiute. Here, she informs her public that the reservation lands were sold against the wishes of her community, implying no community members were in a position to push back against the sale of the land. Still, while being more informative here she does not abandon the impassioned language from earlier in the circular. She states, “I want to test the right of the United States government to make and break treaties at pleasure.” She finishes by saying “Talk for me and help me talk, and all will be well.” On January 4, 1884, she went before Congress with a petition for the restoration of the Malhuer Reservation to the Paiute.

Unfortunately, the lands designated as the Malheur reservation would never be reacknowledged by the government as the Malheur reservation. Winnemucca’s declining health and funds prohibited her from keeping her school running, and she passed away in 1891. Though her work in these areas was not fully realized, Winnemucca was able to fashion a public voice that reached an elite and influential circle of Boston, made herself heard by the United States Congress, and translated her experience to be understood by a broad American public. Her legacy today is controversial and her complicated public advocacy resonates with contemporary debates. The questions of identity and representation are some of the most pressing of our time; the rhetoric of who belongs where is a common topic in popular and political media. Reading through Winnemucca’s “Appeal for justice” and Peabody’s letter offers a historical perspective.

All of the excerpts and images in this post were taken from collections held at the MHS. You can visit our library to take a look at the originals.