By Mary Millage, Reader Services Intern

Mary Millage completed her internship in the Reader Services department in Summer 2019. Her major project was compiling a subject guide for the history of infectious disease in Boston. This blog post came out of that research and highlights one of the collections Mary worked with as part of that project.

– Anna Clutterbuck-Cook, Reference Librarian.

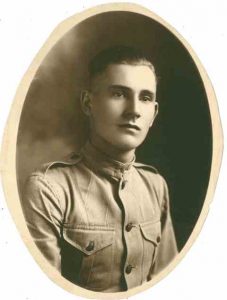

In July 1918, Emerson P. Dibble was 20 years old, and had just arrived at Parris Island, SC for training in the United States Marine Corps in the midst of the First World War. He was far from his hometown of Southwick, MA, and excited to embark on his new adventure. Ten months later, he was back in the United States after serving in Germany and France and surviving the influenza pandemic. In that time, he had matured a great deal, spent time in numerous military camps and hospitals, and contracted tuberculosis, which would eventually kill him. His letters home during this time are filled with personality, and by reading his words, it is easy to picture this lively young man as he relayed his experiences to his family.

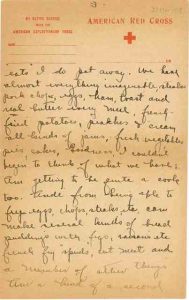

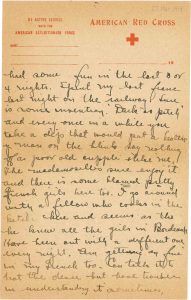

Although his letters primarily cover just a few short years, they provide a human lens through which to examine important topics, such as the First World War and the influenza pandemic. Despite never seeing combat while in Europe, Dibble’s letters describe many aspects of soldiering, from drill to guard duty to the food. His letters shine light on the less glamorous day-to-day features of military life. He writes about many topics that most soldiers could speak to—food, care packages, camp conditions—but that do not fit the typical image of the First World War’s trenches and battles. Throughout his time in the military, Dibble retains his sense of humor and excitement about new experiences. He describes eating watermelon on the train ride to Parris Island, working in the kitchens at a military hospital in Bordeaux, and meeting French girls. He also describes the harsher realities of war: homesickness, worrying about his family, and the inconsistencies of the mail delivery. Across ten months, he matures a great deal without losing his sense of humor and liveliness.

The portions of his letters that most clearly show his maturation are those that discuss the influenza pandemic. Dibble’s letters display the evolution of his feelings about the influenza and his fears for his family back home. At first, he is unconcerned with the outbreak and is convinced that it is simply the common flu. As time goes on and he begins to hear of the seriousness of the outbreak, and especially once he is in Europe and large passages of time go by without letters from home, he becomes increasingly concerned about his family and fearful of hearing that any of them are sick. Despite Dibble himself falling ill with influenza, he is still most concerned about his family and their health. Through these letters, the fear he was feeling and the uncertainty of the time are clear and moving. He even writes to his stepmother, Millie, that if it was not for his fiancé, Olive, he “wouldn’t care a d—n about coming back to the States if either” Millie or his father died of influenza (Emerson P. Dibble to Millie Holcomb Dibble, 18 January 1919).

Through his letters, you really get a sense of Dibble and feel connected to him. The happiness and hardships he faced blend together into a compellingly human story. He was bored by the regimentation of the military but felt it was good for him, he frequently used slang in his letters and enjoyed learning French and German phrases, and he worried about his family while urging them not to worry about him. By the time he returns to the United States in May of 1919, you feel connected to this young man, which is part of why the last years of his papers are so difficult to read. When he returned to the United States, he was already ill with tuberculosis, although he did not yet know this. In three years, he was dead. He returned stateside happy to be close to going home and convinced that the doctors would soon cure him. His fast decline is jarring and heartbreaking. He was of his time, a time that was deadly through war and disease. His letters are full of personality and provide us with an unflinchingly human look at the time in which he lived. Although Emerson P. Dibble did not live to be very old, his letters can teach us a great deal about him and the time in which he lived.