by Doug Girardot, Adams Papers Intern

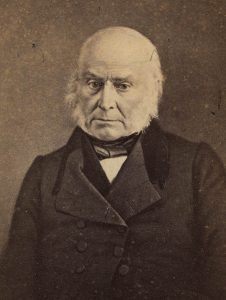

There was just one problem: I didn’t care about John Quincy Adams. What’s more, I knew almost nothing about him, apart from the fact that he was John Adams’s son and served as president.

As it turns out, your perceptions of someone change a lot when you read dozens upon dozens of pages from their personal diary. After transcribing and proofreading several months’ worth of his writings and doing web encoding for over a year of entries, I ended up getting to know quite a bit about the ins and outs of John Quincy Adams. Three months or so later, I think JQA, as we affectionately abbreviate him in the Adams Papers, is one of the most fascinating figures in American history.

JQA kept a behemoth of a personal record: his diary comprises fifty-one volumes, which he wrote over the course of 68 years beginning when he was twelve years old. They provide an unparalleled window onto the period between the nation’s founding in the last quarter of the 1700s and the time when a distinct national identity of the United States began to coalesce by the mid-1800s.

Despite the Homeric scale of his diaries, their small details are even more interesting than the grand geopolitical narratives which they convey.

His writings about religion are fascinating, and it’s amazing to glance into what religion looked like in the adolescent years of an independent America. Every Sunday, JQA quoted the readings from church and summarized the preacher’s sermon. Then, he bluntly—and often ruthlessly—critiqued the homilist’s eloquence and speaking style before proceeding to give his judgement on the theological contents and coherence of the sermon itself. About Rev. William Newell, minister of the First Parish of Cambridge, JQA wrote:

“His discourses are sensible and moral, but neither brilliant nor profound. The theological school at Cambridge, is yearly producing several such clergymen, and they are introducing a uniformity of composition and delivery, superior to those of their predecessors of the last age, but which leaves a desire for more variety at least of manner—” (28 August 1836)

Good reviews from JQA—something like the Roger Ebert of his time for religious services—were few and far between.

And while it is intellectually interesting to read about his solemn take on religion, it is outright fun to read words crafted in his decidedly less pious side. Peppered throughout his diary are insults which only a well-traveled, bookish, Harvard-educated, diplomat-turned-president-turned-legislator could concoct. Take this passage from his time in Congress, in which he gracefully provided his thoughts on prospective presidential candidates for the election of 1844:

“Buchanan is the shadow of a shade and General Scott is a Daguerrotype likeness of a candidate—all sunshine, through a camera obscura. . . . M’Lean, is but a second edition of John Tyler—vitally democratic, double-dealing and hypocritical—” (3 April 1843)

While at first it can be challenging to connect with someone from around two hundred years ago, for whom daguerreotype was modern technology, a further look provides glimpses of timeless humanity that makes JQA resemble what he really was—a person.

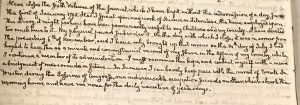

This comes through in his reflections on the quotidian tasks of keeping up with his correspondence, diary, and speeches, all of which he spent countless hours composing in addition to his regular duties as a statesman. Though JQA may have been a prolific and erudite writer, it didn’t come easily. Many a student in the midst of a paper can relate to his comments regarding backlogged diary entries which he was working on:

“Had I spent upon any work of Science or Literature, the time employed upon this Diary, it might perhaps have been permanently useful to my Children and my Country— I have devoted too much time to it— My physical powers sink under it—” (20 March 1821)

More than simply an austere historical figure, JQA strikes me in his writing as a genuinely good person, striving to do what was right. Toward the end of his life, he undertook the writing of a speech to advocate for the abolition of slavery. While it was a daunting and exhausting project, JQA pressed on, determined

“to leave behind me something which may keep alive the flame of liberty and preserve it in that conflict between Slavery and freedom which is drawing to its crisis and which is to brighten, or to darken the condition of the human race upon earth—” (11 April 1843)

Keeping up with his writing might have been a constant source of pressure for JQA, but I am certainly grateful that he did it anyway. Without these invaluable records, he might well have remained just another name in a textbook for me. Fortunately, interning at the MHS has furnished me the opportunity to discover the vibrant, devoted, intelligent, sometimes curmudgeonly, but always loveable character that he was.

Doug, I enjoyed reading about your growing admiration for JQA. And through it all, let’s not forget the tragedy he his wife Louisa endured with the early deaths of their two sons – George (jumped overboard on his way to Washington to accompany his father home after 1828 defeat) and John who succumbed to alcoholism at age 31. Fortunately JQA had his remaining son Charles Francis to pick up the pieces and go on to lesser glory. It’s a fascinating story. Good luck in your historical career!

Doug, thanks for sharing your enthusiasm about JQA’s diaries. Fascinating accounts. And through it all, he and his wife Louisa suffered the loss of two of their sons. George jumped ship on his way to Washington to accompany his parents back to Quincy after JQA’s defeat by Andrew Jackson in 1828. A second son John died a few years later from alcoholism at age 31.

Fortunately, the family had the youngest son, Charles Francis, to pick up the pieces and redeem the Adams clan with his writing, diplomatic service, and rearing his own large brood with dignity. Fabulous story.

Best of luck with your historical career… Helen Breen, Lynnfield