By Susan Martin, Processing Archivist & EAD Coordinator

This is the sixth post in a series. Read Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV, and Part V.

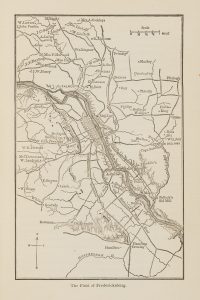

We return today to the story of Dwight Emerson Armstrong of the 10th Massachusetts Infantry. About two weeks after we left him, Dwight’s regiment fought in the Battle of Fredericksburg, Va., 11-15 December 1862.

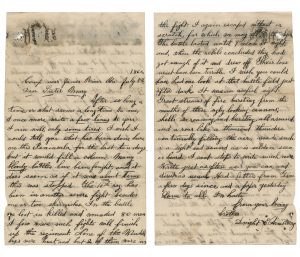

Dwight described the battle to his older sister Mary (Armstrong) Needham in a detailed eight-page letter, dated 21 December. He’d survived “without a scratch,” but there was no denying that Fredericksburg was a devastating loss for the Union. Dwight told Mary about the perilous crossing over the Rappahannock River via pontoon bridge, under fire, in the bitter cold, as well as the uncanny proximity of the enemy in the dark (“we could hear them cough”).

After the battle, writing from the relative safety of the Union camp at Falmouth on the other side of the river, Dwight was still shaken: “It makes me almost tremble now, when I think what a hole we were in. […] Some one is to blame for all this loss of life; and who it is time will show.” However, he reassured Mary, as he usually did, and with his characteristic humor.

You need not give yourself any trouble about my sufferings; it is not so bad as you imagine it to be. I have got toughened to it, so that heat, and cold, storm, and sunshine, have as little effect on me, as it does on that old bundle of cloaks, and hoods that used to travel around in Wendell [Mass.] with Aunt Sally Taft inside of them.

Dwight may have been “toughened,” but he was also very discouraged. He asked, “What have we gained? I know something of what we lost.” And he wasn’t alone. On 4 December 1862, an article appeared in a Massachusetts paper, the Springfield Republican, written by Springfield’s own William Birnie. Birnie was just back from a good-will visit to Union troops in Virginia. In his article, he described the men of the 10th Regiment as “demoralized,” “disaffected,” and “disheartened.”

His words received some backlash, but judging from Dwight’s letters, they were true. In fact, Dwight was probably quoting Birnie when he called his own regiment “the demoralized 10th.” Dwight was especially angry at politicians in Washington who sent men to fight but took “good care to keep beyond the range of the bullets.” He told Mary that he hoped no more men would be drafted.

I hope there wont a man come as long as things go on at this rate. As long as there is such a set of numbskulls in Washington it is throwing away lives for nothing. […] All he [General-in-Chief Henry Halleck] ever was put in command for, was because he was such a short-sighted old blunderbuss.

It was during this time that Dwight wrote what I think are some of his most compelling letters. First there’s this passage:

I do hope, though, that something will be done to stop this miserable buisness, before many weeks. I beleive if the privates of both armies, could get together, they could settle it pretty easy. The day before we recrossed the Rappahannock, there was’nt any fighting in the part of the field where I was; and our skirmishers, and theirs […] got up a treaty of peace among themselves; each side agreeing not to fire on the other unless obliged to do so. They had a fine time, and appeared to be great friends, for such enemies. It did look odd enough, to see the same men, who the day before were doing their best to kill each other talking together, and swapping whiskey and tobacco, for coffee and salt, and such like.

The day Dwight is describing is 14 December 1862, right in the middle of the Battle of Fredericksburg. The two sides had been firing at each other the day before, but on the 14th there was a lull in the fighting as both Union and Confederate troops waited in reserve on the field. The battle resumed the following day, and the South successfully drove the North back across the Rappahannock.

Now on separate sides of the river—and in spite of orders to the contrary—the soldiers continued their fraternization. Here’s what happened on 10 January 1863:

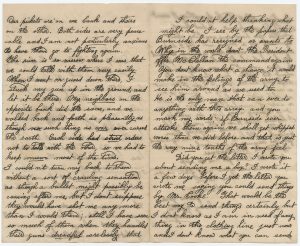

Our pickets are on one bank, and theirs on the other. Both sides are very peaceable, and I am not particularly anxious to have them go to fighting again. The river is so narrow, where I was, that we could talk with them very easily. When I went on guard down there, I stuck my gun up in the ground, and let it be there. My neighbors on the opposite bank did the same, and we walked back and forth, as pleasantly as though no such thing as war ever cursed the earth. Each side had strict orders not to talk with the other, so we had to keep mum most of the time. I couldn’t turn my back to them without a sort of crawling sensation, as though a bullet might possibly be coming after me, but I dont suppose they would have shot me any more than I would them.

These illicit meetings are confirmed in Joseph K. Newell’s 1875 history of the regiment, “Ours”: Annals of the 10th Regiment, Massachusetts Volunteers in the Rebellion. (Newell was himself a member of the 10th.) The soldiers even used a small sailboat to exchange newspapers, coffee, tobacco, and personal messages.

Join me in a few weeks here at the Beehive for the next installment of Dwight’s story.