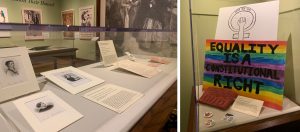

Commemorating 100 years since Massachusetts ratified the 19th Amendment, a new exhibition at the MHS explores the activism and debate around women’s suffrage in Massachusetts. Featuring dynamic imagery from the collection of the MHS, “Can She Do It?” Massachusetts Debates a Woman’s Right to Vote illustrates the passion on each side of the suffrage question. The exhibition is open through 21 September 2019, Monday and Wednesday through Saturday from 10:00 AM to 4:00 PM, and Tuesday from 10:00 AM to 7:00 PM.

For over a century, Americans debated whether women should vote. The materials on display demonstrate the arguments made by suffragists and their opponents. While women at the polls may seem unremarkable today, these contentious campaigns formed the foundations for modern debates about gender and politics.

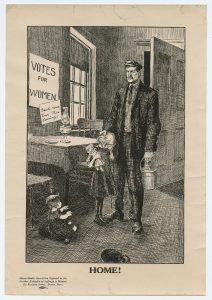

Winning the right to vote required more than just passing legislation. Suffragists needed to convince the public to accept new gender roles for women. Anti-suffragists held firm that women should focus on family. They argued that politics would threaten their feminine virtues, damage the family, and ultimately destroy American society. Cartoons suggested that women would abandon their homes and families to cast ballots. In 1895, Massachusetts men and women founded the nation’s first anti-suffrage organization and led campaigns against the suffragists. Visitors are able to see examples of propaganda such as Home!

After a century of such criticisms, in the 1890s, suffragists argued that female voters would actually improve American life. They contended that women would clean up corrupt politics and favor initiatives to support families. Through their visual campaign materials, they demonstrated that woman could remain feminine, run households, and cast ballots. Not only would female voters continue to care for their families, they would do it better. One example on display is Double the Power of the Home, a broadside by local artist Blanche Ames that depicts a white middle-class mother at home with her children. According to the suffragists, this type of woman would cast a “good vote” in favor of her family.

The exhibition highlights racial divisions among the suffragists. After being excluded from prominent white organizations, Bostonian Josephine Ruffin organized the first national organization of black women, the National Association of Colored Women. Viewers will encounter portraits of black leaders as well as political cartoons that illustrate these tensions.

As the debate continued into the 20th century, British suffragists and labor activists inspired American suffragists to organize parades and pickets to attract attention. In 1915, about 15,000 suffragists marched in a “Victory Parade” in Boston. Suffrage supporters sported yellow roses or sashes while opponents displayed pink and red roses. A broadsheet with instructions for marchers participating in the 16 October 1915 parade is on display along with a scrapbook containing photos from the parade. Eleven states had granted women the ballot and suffragists hoped Massachusetts would be next. The referendum failed. Only 133,000 men voted for the measure, while almost 325,000 voted to defeat it.

On June 25, 1919, Massachusetts ratified the Nineteenth Amendment which prohibited states from barring voters based on sex. The final state ratified the measure the following year and many women voted in the 1920 presidential election. Yet, not all women were guaranteed the right to vote. For example, literary tests, poll taxes, and violence prevented black men and women from voting. On August 6, 1965, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was signed into law prohibiting racial discrimination in voting.

Debates over access to the polls continue today, and Americans continue to advocate for social justice. In 2017, the Women’s March, which developed a platform that included a range of women’s rights, became the largest protest in the nation’s history. Items from the Women’s March including posters and a pussy hat are on display. Social movements and public protests continue to evolve, but the ballot remains an essential expression of political power.

A series of videos highlighting materials from the collection of the MHS are available to view in an interactive display. The videos were created by students at the Wentworth Institute of Technology. Allison Lange, their professor and the exhibition curator, developed this project as part of her class curriculum. The assignment prompted students to craft a three- to four-minute video about the debate over women’s rights in Massachusetts.