“Can She Do It?”: Massachusetts Debates a Woman’s Right to Vote is now open at the MHS and we are starting off the week with a talk by the show’s guest curator Allison Lange, Wentworth Institute of Technology. A brown-bag lunch program on Wednesday followed by a tour, a workshop, and a talk on Saturday round out the week. Here’s a look at what is planned:

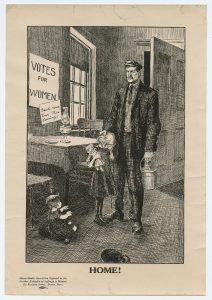

On Monday, 29 April at 6:00 PM: Visual Culture of Suffrage with Allison Lange, Wentworth Institute of Technology. As we have seen from the portraits of women selected to appear on the new ten-dollar bill to the posters featuring suffragists carried at the 2017 Women’s March, the visual culture of the suffrage movement still makes news today. Allison Lange will speak about the ways that women’s rights activists and their opponents used images to define gender and power throughout the suffrage movement. This program is a part of ArtWeek. A pre-talk reception begins at 5:30 PM; the speaking program begins at 6:00 PM.

On Wednesday, 1 May at 12:00 PM: Shinbone & Beefsteak: Meat, Science, & the Labor Question with Molly S. Laas, University of Göttingen Medical School. Could better nutrition help shore up U.S. democracy in an era of mass inequality? This talk explores the early years of nutrition science in the late nineteenth century by examining the science’s use as a tool for cultural and political change. By looking at how scientists understood the relationship between wages, the cost of living, and better nutrition, this paper will shed light on the political life of scientific ideas. This is part of the Brown-bag lunch program. Brown-bags are free and open to the public.

On Saturday, 4 May at 10:00 AM: The History & Collections of the MHS. This is a 90-minute docent-led walk through of our public rooms. The tour is free and open to the public. If you would like to bring a larger party (8 or more), please contact Curator of Art Anne Bentley at 617-646-0508 or abentley@masshist.org.

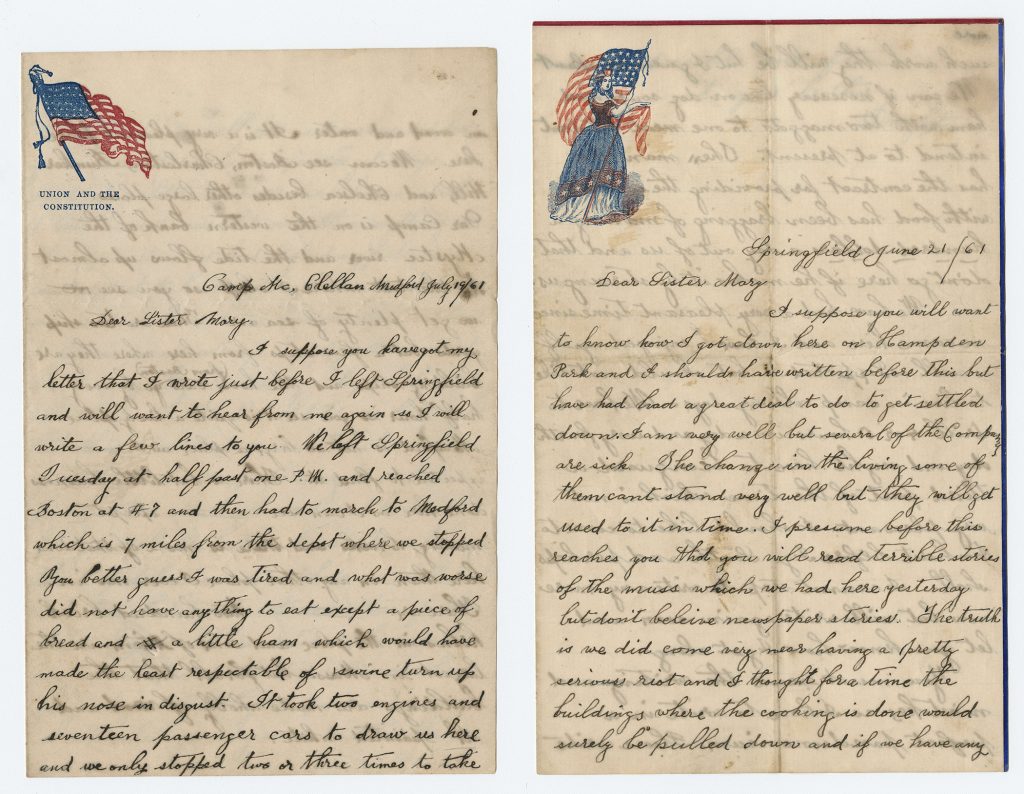

On Saturday, 4 May from 11:30 AM to 1:00 PM: Preserving Family Papers with MHS staff. Do you have boxes full of family papers and photographs sitting in your closet, basement, or attic? Are you wondering how to best preserve those precious memories for generations to come? Let the experts at the MHS teach you simple steps you can take to preserve your paper-based materials. This workshop concludes with a behind-the-scenes tour including our conservation lab and library stacks. Please note that registration for this workshop is now full.

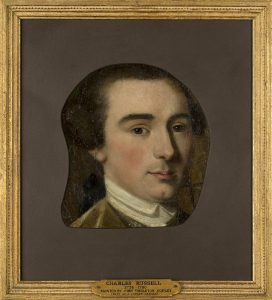

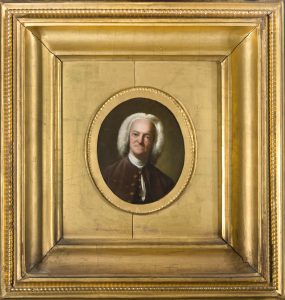

On Saturday, 4 May at 4:30 PM: The Problem of Democracy: The Presidents Adams Confront the Cult of Personality with Nancy Isenberg and Andrew Burstein. John and John Quincy Adams were brilliant, prickly politicians and arguably the most independently minded among leaders of the founding generation. Distrustful of blind allegiance to a political party, they brought skepticism of a brand-new system of government to the country’s first 50 years. Join Isenberg and Burstein as they boldly recast the historical role of the Adamses and reflect on how father and son understood the inherent weaknesses in American democracy. A pre-talk reception begins at 4:00 PM; the speaking program begins at 4:30 PM. There is a $10 per person fee (no charge for MHS Fellows and Members or EBT cardholders).

“Can She Do It?”: Massachusetts Debates a Woman’s Right to Vote is open Monday and Wednesday through Saturday from 10:00 AM to 4:00 PM, and Tuesday from 10:00 AM to 7:00 PM. Featuring dynamic imagery from the collection of the MHS, the exhibition illustrates the passion on each side of the suffrage question. For over a century, Americans debated whether women should vote. The materials on display demonstrate the arguments made by suffragists and their opponents. While women at the polls may seem unremarkable today, these contentious campaigns formed the foundations for modern debates about gender and politics.

Take a look at our calendar page for information about upcoming programs.