by Susan Martin, Processing Archivist & EAD Coordinator

The Shattuck family of Boston, Mass. consisted of father Lemuel, mother Clarissa (née Baxter), and five daughters: Sarah, Rebecca, Clarissa, Miriam, and Frances. The MHS recently acquired some papers of eldest daughter Sarah White Shattuck, primarily letters to and from family members while she was a student at Bradford Academy in Haverhill, Mass. The collection gives us not only a detailed picture of a young woman’s education in 19th-century New England, but also an intimate look at some interesting family dynamics.

Bradford Academy, founded in 1803, was one of the premier schools for girls when Sarah began her studies there in April 1841 at the tender age of 13. Sarah’s letters include a lot of terrific detail about the school and its curriculum. Sarah learned philosophy, history, geography, algebra, chemistry, geometry (she was a big fan of Euclid), physiology, astronomy, French, and grammar and spelling (“these two studies they are the most particular with,” she said). There were prayers and Bible readings every morning.

This was a formative time for Sarah, both academically and socially. She seems to have flourished under the tutelage of several female role models, including the school’s teachers and especially its principal, Abigail C. Hasseltine. Sarah also took piano and singing lessons with Mary Noyes, the daughter of Deacon Daniel Noyes.

Sarah’s correspondents were her parents, her sisters, her uncle Daniel Baxter, and her aunt Sarah Baxter. The bulk of the letters, however, came from her father. Lemuel had little formal education himself, but had worked as a teacher, merchant, bookseller, publisher, and historian. He served on the Boston City Council and in the Massachusetts House of Representatives and was one of the founders of the MHS’s sister organization, the New England Historic Genealogical Society. (He was also a member of the MHS.) Unsurprisingly, Lemuel had high standards for his daughter’s education and high hopes for her success.

Lemuel advised Sarah on almost everything, particularly her courses and reading. Of botany, for example, he said, “there is no branch of knowledge—scientific knowledge I mean—better calculated to display the wonders of creation.” He also corrected her manners, at one point disapproving of certain “impudent expressions” and “unjust remarks” she’d made about other people. He critiqued her letters. He even had an opinion about the temperature of her room.

At times you feel sympathetic to Sarah for these well-meaning but incessant correctives from the paterfamilias. She couldn’t seem to catch a break. In one letter Lemuel would insist she work hard, and in the next warn her that working too hard may damage her health. However, Sarah was grateful for the opportunity to attend Bradford and never forgot the expense and trouble her parents were going to for her benefit.

When she complained of homesickness, Lemuel usually told her not to indulge it. But he wrote with great compassion on one particular occasion: Thanksgiving 1841. Sarah was staying at school for the holiday, and the few remaining students who occupied the mostly empty boarding house were girls she didn’t know well. She felt lonely and homesick to the point of tears. Lemuel wrote on Thanksgiving day to tell her how much the family missed her, too. Then he suggested she reach out to the other students, and his advice was kind and uncritical.

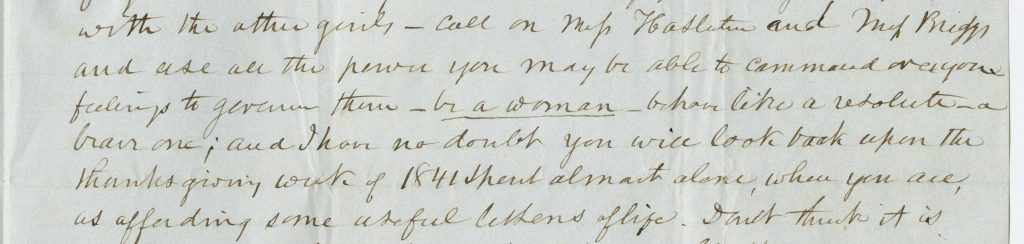

Cull all the sweets and beauties from all the flowers that dwell under your roof, and let the fragrance of your own character be manifest to all others. After all, dear Sarah, this incident in your life may have its uses to you. Think of it rightly – your dear father meant to do right – there you are – lonely to be sure for a few days, but a few days soon pass away. Think how important it is that our minds should be di[s]ciplined to some little trials – try and surmount all you now experience – Resolve that you will make the best of your situation – […] use all the power you may be able to command over your feelings to govern them – be a woman – behave like a resolute, a brave one.

Sarah was only 14 years old, but this letter and others in the collection tell us a lot about their relationship. Lemuel may have scolded, but he was also very proud. He sometimes wrote to her about his own work and even asked her advice on the best school for her younger sister Rebecca. When Sarah worried about her exams, he encouraged her to be confident and to “overcome all diffidence […] there is no occasion for it in you.”

Unfortunately, the Shattuck family had its tragedies, as well, just like all of these old families. Two of the sisters died of consumption just a few months apart: the youngest sister Frances in 1850, at the age of 15, followed by 21-year-old Rebecca. Sarah wrote lengthy and moving tributes to both of them in her diary. (The collection also includes several letters by Rebecca.) Clarissa, the middle sister, died in 1858, 15 days after the birth of her third child. Lemuel died in 1859, and mother Clarissa in 1871.

Sarah married her first cousin, John Henry Shattuck, in 1849. The couple had at least one child, Lucy, before Sarah died on 4 February 1863 at the age of 35. Miriam lived until 1909, decades longer than the rest of her family.

I’ll let Lemuel have the last word. Here’s how he concluded one of his letters:

And now dear Sarah what shall I say further? If I say what I have so often said – love – love – love of all of us, sincere and ardent, is ever yours, it is but a repetition of the old story, but it is nevertheless as fresh and blooming as if it never had been told, and appears as a flame that never grows dim. O Sarah may you be returned to us in safety and in happiness and may you be prepared to enjoy or endure any event that may happen in all your future life.

Select references:

Barrows, Elizabeth A. A Memorial of Bradford Academy. Boston: Congregational S.S. and Publishing Society, 1870.

“Lemuel Shattuck.” Memorial Biographies of the New England Historic Genealogical Society: Towne Memorial Fund. Vol. III. Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 1883. pp. 290-321.

Lemuel Shattuck papers, Massachusetts Historical Society.

Shattuck, Lemuel. Memorials of the Descendants of William Shattuck, the Progenitor of the Families in America That Have Borne His Name. Boston: Printed by Dutton and Wentworth for the family, 1855.

The MHS holds other material related to Bradford Academy, including printed items, papers of teacher and principal Rebecca Gilman, and papers of student Martha Dalton Gregg, a contemporary of Sarah’s.