By Gwen Fries, Adams Papers

When Abigail Adams arrived in France in August 1784, she must have felt like she had just landed on the moon. In all 39 years of her life, Abigail had never been south of Plymouth, north of Haverhill, west of Worcester, or east of Massachusetts Bay.

Twelve years earlier, Abigail wrote a letter to her cousin Isaac Smith Jr., who was traveling in London. She wanted to ask him “ten thousand Questions” about Europe. “Had nature formed me of the other Sex, I should certainly have been a rover,” she told him. Abigail explained to Isaac that it was too dangerous for a woman to travel alone and that by the time a woman has a husband with whom to travel, she also has a house to maintain and children to raise, creating “obstacles sufficent to prevent their Roving.” Already a mother of a 5-year-old, 3-year-old, and an 11-month-old, Abigail believed she had missed her chance to travel. “Instead of visiting other Countries; [women] are obliged to content themselves with seeing but a very small part of their own.” For these reasons, she told Isaac, “to your Sex we are most of us indebted for all the knowledg we acquire of Distant lands.”

One can’t help but wonder if Abigail remembered writing those words as her carriage bounced through the French countryside en route to her new residence in Auteuil, just outside of Paris. Whether or not she remembered that specific letter, she remembered the feeling of being stuck at home while her male relations traveled. She determined to write long, detailed letters to her female acquaintances, especially her nieces Elizabeth and Lucy Cranch, in an attempt to expand their worldview and to provide them with a female’s perspective of Europe.

In her letters to Elizabeth and Lucy, Abigail described the architecture of theatres, the designs of French gardens, and holiday customs. But John or John Quincy could have done that. That’s one of the things that makes Abigail’s letters remarkable—that she bothered to write to her nieces at all—something their uncle and cousin had largely neglected to do.

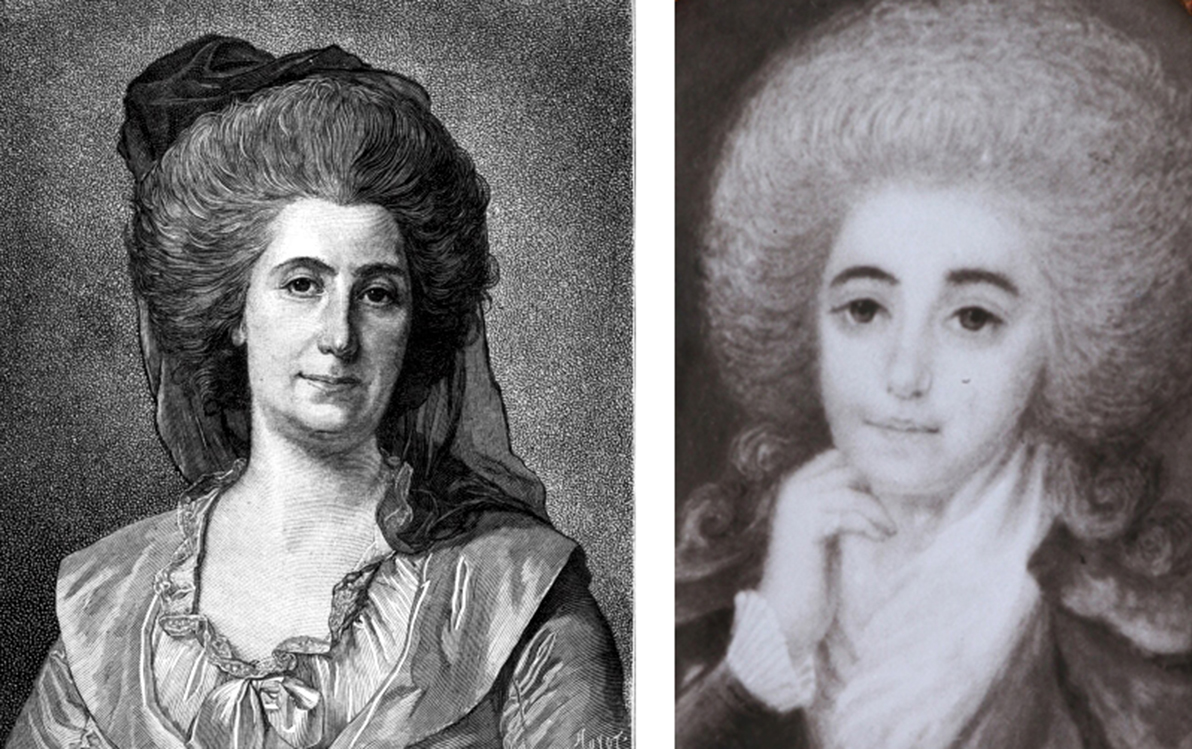

Left: Anne-Catherine de Ligniville, Madame Helvétius; Right: Marie Adrienne Françoise de Noailles, Marquise de Lafayette

Left: Anne-Catherine de Ligniville, Madame Helvétius; Right: Marie Adrienne Françoise de Noailles, Marquise de Lafayette

Travel books could describe architecture and provide maps, but there wasn’t one that provided a New England woman’s perception of French women. Though her correspondents entreated Abigail to divulge what French women were actually like, Abigail really only became acquainted with two women during her nine months in France—Dr. Franklin’s friend Madame Helvétius and the Marquise de Lafayette. The former “highly disgusted” her with her untidiness of dress and lewd manners; the latter charmed her immediately. When she arrived at the Lafayettes’ front door, “the Marquise. . .with the freedom of an old acquaintance and the Rapture peculiar to the Ladies of this Nation caught me by the hand and gave me a salute upon each cheek, most heartily rejoiced to see me. You would have supposed I had been some long absent Friend, whom she dearly loved.”

Unless she was with the Marquise, who spoke English well, Abigail felt isolated by her ignorance of the French language and took to observing rather than conversing. “It is from my observations of the French ladies at the theatres and public walks, that my chief knowledge of them is derived,” she explained to family friend Hannah Quincy Lincoln Storer. She accordingly described what French women communicated beyond words: “The dress of the French ladies is, like their manners, light, airy, and genteel. They are easy in their deportment, eloquent in their speech, their voices soft and musical, and their attitude pleasing.”

She observed to her sister Mary that “Fashion is the Deity every one worships in this country and from the highest to the lowest you must submit.” During her stay in Europe, Abigail mailed fashion magazines and patterns home so her friends could see what was a la mode and included silk or ribbons whenever possible so they could try the designs for themselves. She gave strict instructions, such as that “the stomacher must be of the petticoat color” and “gowns and petticoats are worn without any trimming of any kind.” Abigail added that Marie Antoinette had set the trend of “dressing very plain. . .but caps, hats, and handkerchiefs are as various as ladies’ and milliners’ fancies can devise.”

Marie Antoinette en chemise, 1783 portrait by Louise Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Marie Antoinette en chemise, 1783 portrait by Louise Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Abigail never resigned herself to French attitudes towards sex and marriage, but she came to admire the easy elegance of French women and found herself missing them when she, John, and their daughter, Nabby, relocated to London in April 1785. She noticed that the English tried to copy French fashions but ended up “divest[ing] them both of taste and Elegance.” Abigail’s brush with European style convinced her that “our fair Country women would do well to establish fashions of their own; let Modesty be the first, ingredient, neatness the second and Economy the third. Then they cannot fail of being Lovely.”