By Sara Georgini, The Adams Papers

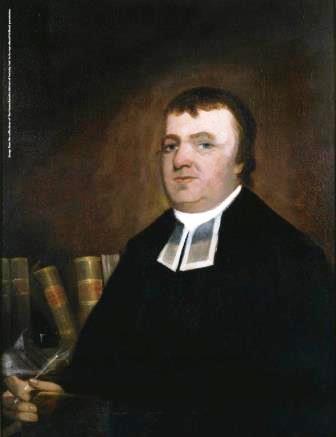

Like so many good stories here at the Historical Society, it began with a reference question. Jeremy Belknap, hunting through his sources, asked Vice President John Adams for some help. Belknap, the Congregationalist pastor of Boston’s Federal Street Church, had spent the past few years amassing manuscripts for several major research projects. By the summer of 1789, he was deep into writing the second volume of his History of New Hampshire, a sprawling trilogy that he built, slowly, with meticulous footnotes. The clergyman, who honed his narrative skill as a Revolutionary War chaplain and biographer, felt thwarted by a lack of access to key documents.

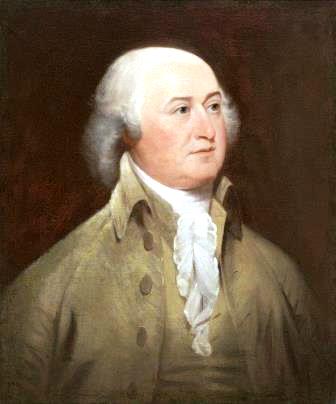

John Adams, 1735-1826.

Jeremy Belknap, 1744-1798.

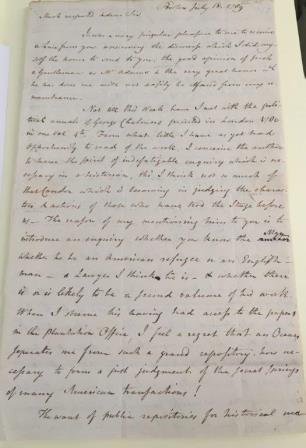

After poring over George Chalmers’ Political Annals of the Present United Colonies from their Settlement to the Peace in 1763 (London, 1763), Belknap wrote to Vice President John Adams to see if he knew more about the Scottish antiquarian’s research methods. Mainly, Belknap wanted to see how Chalmers pieced together his saga of America as a “desert planted by English subjects” and made fruitful by the flourishing of English liberties. On 18 July, Belknap wrote: “When I observe his having had access to the papers in the plantation Office, I feel a regret that an Ocean seperates me from such a grand repository. how necessary to form a just judgment of the secret springs of many American transactions!” Jeremy Belknap’s query – and Adams’ detailed reply – form one of the most significant exchanges that we will feature in Volume 20 of The Adams Papers’s The Papers of John Adams (Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2020).

Though the nation was new, Americans like Belknap hungered to capture their history in print. While British scholars flocked to the Society of Antiquaries of London and dug through government office records, early American scholars lacked similar institutions and resources to conduct historical research. Across Massachusetts, precious family manuscripts and rare artifacts piled up in private homes and flammable steeples. When Belknap looked around Boston in 1789, he lamented how fire and plunder had ravaged materials held in the city’s courthouse (1747), the Harvard College Library (1764), Lt. Gov. Thomas Hutchinson’s home (1765), the Court of Common Pleas (1776), and Thomas Prince’s cache at the Old South Church (1776). Belknap began sketching out what became the Massachusetts Historical Society: a scholarly membership organization (of no more than seven!) that collected materials and published research. He found a fellow visionary in John Pintard, who led efforts to found the New-York Historical Society.

Jeremy Belknap to John Adams, 18 July 1789, Adams Family Papers.

Adams and Belknap had traded letters before, and they would continue to do so until the pastor’s death in 1798. This one touches directly on his plans to create the Society. Founder to founder, Belknap put the problem plainly:

The want of public repositories for historical materials as well as the destruction of many valuable ones by fires, by war & by the lapse of time has long been a subject of regret in my mind. Many papers which are daily thrown away may in future be much wanted, but except here & there a person who has a curiosity of his own to gratify no one cares to undertake the Collection & of this class of Collectors there are scarcely any who take Care for securing what they have got together after they have quitted the Stage. The only sure way of preserving such things is by printing them in some voluminous work as the Remembrancer—but the attempt to carry on such a work would probably not meet with encouragement—

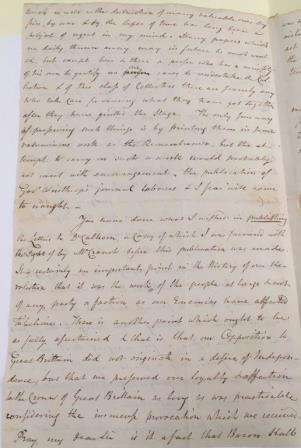

John Adams to Jeremy Belknap, 24 July 1789, Belknap Papers.

In Adams, Belknap found a high-profile ally. A longtime supporter of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the statesman had championed the new nation’s intellectuals abroad. He approved wholly of Belknap’s instinct. Despite his duties presiding over the Senate in the first session of the federal Congress, John Adams prioritized Belknap’s query, firing off a reply on 24 July. He shared a few thoughts on Chalmers’ work and filled in details of Revolutionary War history. Then John Adams lingered happily on Belknap’s dream of a historical society. He had a very personal stake in how the national story was told, after all, and he was eager to impart advice. Adams wrote:

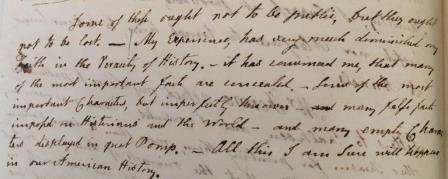

Private Letters however, are often wanted as Commentaries on publick ones.— and many I fear will be lost, which would be necessary to shew the Secret Springs… some of these ought not to be public, but they ought not to be lost.— My Experience, has very much diminished my Faith in the Veracity of History.— it has convinced me, that many of the most important facts are concealed.— some of the most important Characters, but imperfectly known—many false facts imposed on Historians and the World—and many empty Characters displayed in great Pomp.— All this I am Sure will happen in our American History.

Encouragement from John Adams and others led Belknap to dedicate the following months to drafting a concrete plan for the organization’s future. On 24 January 1791, Belknap invited nine colleagues to join him in creating the Massachusetts Historical Society, following up with a detailed circular letter ten months later. John Adams and his family, all ardent advocates of Belknap’s mission to preserve history, have supported the Society ever since, in word and deed.