By Rhonda Barlow, Adams Papers

It was a rainy day in May 1839 and John Quincy Adams, stuck inside, was amusing himself writing poetry. He was trying to imitate the Roman poet Horace, and outdo the English poet Alexander Pope. Horace’s Ode 4.9 encapsulated the idea that without a poet to praise him, the hero was forgotten. Achilles had Homer, Satan had Milton, and Lollius had Horace.

As Pope wrote in his Imitations of Horace,

Sages and chiefs long since had birth

Ere Cæsar was, or Newton named;

Those raised new empires o’er the earth,

And these new heavens and systems framed.Vain was the chief’s, the sage’s pride!

They had no poet, and they died!

In vain they schemed, in vain they bled!

They had no poet, and are dead.

With his sarcastic sense of humor, John Quincy admired Horace, and understood that Horace was being ironic: Lollius was not worthy of a poet, yet would be remembered because of Horace. John Quincy caught the irony with these lines of his own:

The pebble on the beach outshines

The Diamond sleeping in the mines

And hidden from the day.

Who were the poets with the power to rescue the heroes from oblivion? Pope had the advantage of England’s rich literary history, and named John Milton and Edmund Spencer. But the young United States had nothing to compare. Undaunted, John Quincy reached back to the classical past:

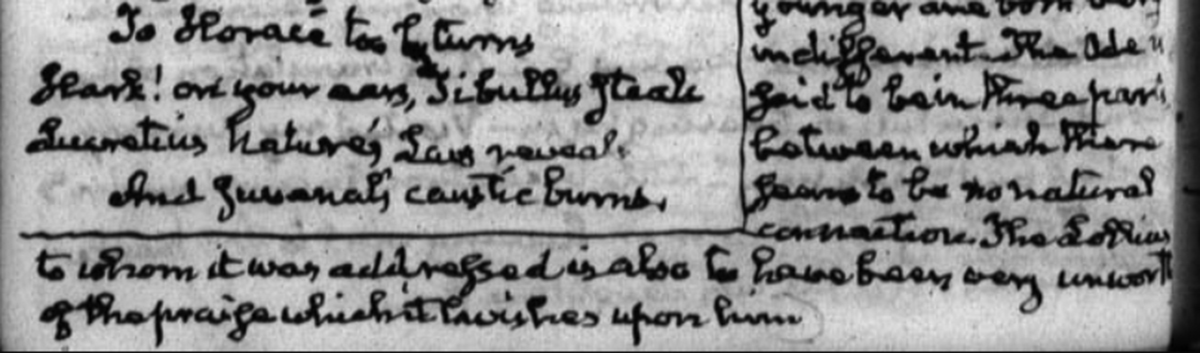

Hark! on your ears, Tibullus steals

Lucretius Nature’s Law reveals

And Juvenal’s caustic burns.

Anyone familiar with the testy satires of the Roman poet Juvenal can appreciate the jauntiness of the final line. As John Quincy wrote in the margin of his diary, “and here I stick on the borders of nonsense.”

John Quincy spent days working on his poem, captivated by the idea that both the poet and the hero could escape death: “What a magnificent panegyric upon his friend. What consciousness of his own transcendent powers! what a sublime conception of the gifts of poetical inspiration!”

He had not always held Horace’s “consciousness” in such high esteem. Fifty-three years earlier, John Quincy, after reading Horace boast that “I have built a monument more lasting than bronze” and “a great part of me shall escape death,” wrote in his diary:

“I finished this morning the third book of Horace’s Odes. Many of them are very fine, and the last one shows he was himself, sufficiently Sensible of it. When a Poet promises immortality to himself, he is always on the safe side of the Question, for if his works die with him, or soon after him, no body ever can accuse him of vanity or arrogance: but if his predictions are verified, he is considered not only as a Poet, but as a Prophet.”

John Quincy Adams’ diary permits us to see his long engagement with Horace, from his days as a schoolboy to the closing years of his life. As he wrote to his brother, Thomas Boylston, in 1802: “When once a man takes up Horace, it is not easy to lay him down again.”