By Susan Martin, Processing Archivist & EAD Coordinator

In June 1854, the Boston City Missionary Society appointed a Methodist Episcopal clergyman named Luman Boyden to serve as missionary to the poor in East Boston. The 48-year-old Boyden (pictured above, about ten years later) had had a distinguished 20-year career as a minister in Sudbury, Oxford, Dorchester, Chelsea, Fitchburg, Holliston, Spencer, Roxbury, Salem, and Waltham. The Society offered him a salary of $650 a year, and he would earn an additional $200 preaching at Union Chapel in East Boston.

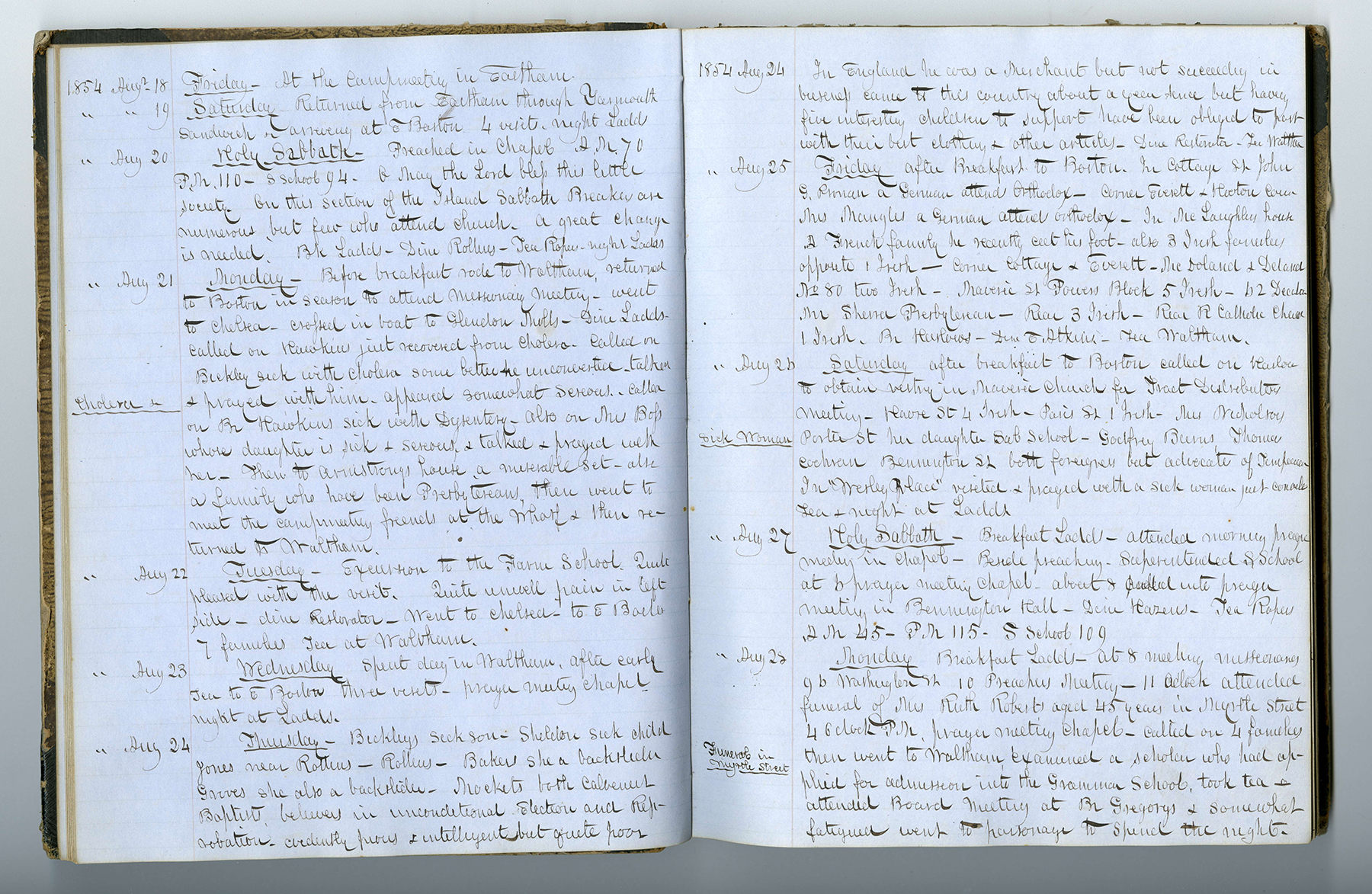

Earlier this year, the MHS acquired four manuscript journals Boyden kept during this time, 1854-1863, primarily documenting his missionary work. He wrote in them every day and described, in compelling detail, the poverty in East Boston, as well as the ravages of alcoholism, domestic violence, other crimes, suicides, and illnesses such as tuberculosis, smallpox, and typhoid fever. Boyden visited the homes of Protestant, Irish Catholic, African American, and immigrant families, many suffering from terrible privation. His journals are a fascinating social history of the city and a record of 19th-century urban life in general.

Rev. Boyden hit the ground running. His first day on the job was 1 July 1854, and just 17 days in, he was attending the family of a Mr. Rose, who had attempted to kill himself by cutting his own throat with a razor blade. Two days later, Boyden visited a woman “putrid with disease,” a young woman dying of consumption, and the family of a suicide victim. He was shocked and horrified by the things he saw. When three people he’d met were arrested for murder, he wrote disbelievingly, “Did not think Monday that I was talking with those who would so soon be considered murderers.”

The pages of Boyden’s journals are filled with daily tragedies. He visited multiple families a day, and while his compassion for the poor was clearly genuine, he was not a disinterested party. One of his primary goals was conversion, and he distributed Bibles and religious tracts and proselytized about sin and salvation. He used language like “den of pollution” and “hive of iniquity” to describe some homes. About others, he simply wrote, “There Satan appears to reign.” As you can imagine, he encountered resistance from Irish Catholic residents, the dominant immigrant group in the neighborhood.

The journals contain a wealth of information, including names and addresses, and some entries go on for multiple pages. In one, Boyden paints a vivid picture of a tenement building as he moves floor to floor, and you also get a sense of his attitude toward the tenants.

Went into Bee Hive No 2 on Havre Street. It is a large old building in the rear of Bee Hive No 1. In each house 16 Tenements which rent for 1 ¼ dollar each week or $65.00 a year. The amount of rent for each year 1040.00. The Hive No 2 is not worth beside land $400.00. […] The houses are owned by a shoe firm in the city & the Tenants make shoes for the firm so the rent is secure & to obtain work the Tenements are filled. […] As I descended flight after flight I found others of the same class, poor, ignorant, depraved & who must be saved or lost forever.

Boyden reserved his fiercest animosity for alcohol. In the margins alongside his text, he scribbled headings like “Rum & Poverty,” “Rum & Beggary,” “Rumsellers Abomination,” etc. Other headings include “Motherless Boy,” “Barefoot Family,” “Poor & Proud,” “Blind Girl in Waltham,” “Furious Woman,” “Singular Case,” and “Children Under Table.”

Speaking of children, many of those Boyden met on his rounds did not attend or had never attended school. Boyden strongly advocated for the education of all children. On 28 September 1854, he wrote about the Nute family.

House kept quite neat, children dressed neatly but in consequence of being colored they are suffering by a most oppressive arrangement. Their children are allowed to attend the primary school with white children but as soon as they become qualified to enter the grammar school, they are not admitted to the schools in E. Boston, but go to the colored school [the Abiel Smith School] in Belknap St about 2 miles from home. In doing this they are obliged to cross the Ferry & pay two cents toll each way. They have three who attend the school in Belknap St at an expense of ferriage of 12 cents a day. […] They feel afflicted that while the dirtiest, vilest white children are admitted that theirs are excluded. Say they have applied to the General School Com[mitte]e but have accomplished nothing. I am resolved to plead their cause.

Incidentally, less than one year later, the Massachusetts legislature passed the first law in the United States prohibiting segregation in public schools. The campaign was led by Benjamin F. Roberts, whose children had also been excluded from the white schools near their home. Roberts had previously lost his case at the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court in Roberts v. City of Boston (1850).

In his journals, Boyden often recorded follow-up visits, so we know how some of the stories developed, who lived and who died, who went to jail or the almshouse, who converted, who repented, and who didn’t. For example, here’s an amazing passage that caught my eye. On 20 March 1857, Boyden visited an African American family on Bennington Street, consisting of Mrs. Russell, her adult daughter, and the daughter’s two children.

[The daughter] is very black & I noticed the infant in her arms was far from being black. I asked if her husband was a pious man? She said I may as well tell the truth, I have no husband. I inquired is not the father to that child a white man? She made no reply, excepting a coarse laugh. I told her that it belonged to the father of the child to support it & I could not help her till he had been seen & if he had anything compelled to aid. […] She has another child about 6 years old the same color. I spoke to her plainly of her wickedness. She said with apparent anger, it is Gods will or it would not be so. The old Lady seemed to feel deeply the ruin of her only child.

Miss Russell told Rev. Boyden the name of her baby’s father, who was white and had a wife and other children. Boyden said he would visit the man, although I couldn’t determine if he ever did. Unfortunately, when he returned to the Russell home about a month later . . .

Her daughter in quite a rage because several weeks since I reproved her as she think[s] to[o] severely. She then said it was the Lords will. I told her it was the work of the devil. She replied that she knew that the Lord made her & he did every child. Today she said the child died several weeks ago.

While most entries relate to Boyden’s missionary and ministerial work, some give us glimpses into his personal life. He and his wife Mary had two children—at the start of the first journal, Helen Maria was 24 and Jeremiah Wesley 15. There had been another daughter, Mary Elizabeth, but she died in 1837 at the age of three. Boyden wrote about her several times.

Luman Boyden died in 1876 at the age of 70. His wife Mary lived until 1897. Both parents outlived their son Jeremiah, who served as a U.S. Navy surgeon in the Civil War before dying of yellow fever at 27. Daughter Helen worked as a teacher, married Thomas Warren Thayer, and died in 1922 at 92 years old.

P.S. Interestingly, Boyden frequently referred in his journals to another missionary for the Boston City Missionary Society, Armeda Gibbs. Gibbs was an abolitionist who helped freedom seekers and is probably best known as the first female nurse for the Union army during the Civil War. Sure enough, Boyden noted on 6 August 1862, “Heard Miss Gibbs offered to go as nurse in the army.”