By Susan Martin, Processing Archivist & EAD Coordinator

In 1849, the ship Lanerk sailed from Boston to California as part of the Gold Rush. On the ship was a clergyman named Truman Ripley Hawley, and the MHS recently acquired a transcript of his diary of the journey. It contains a lot of terrific detail, but one particular digression caught my eye. On 4 August 1849, off the west coast of South America, the Lanerk met the ship Christopher Mitchell, captained by Thomas Sullivan of New Jersey. Sullivan told Hawley about the following “amusing incident”:

He [Sullivan] sailed from Nantucket with his crew, shipped from different states in the union, only one of whom before the mast had ever been to sea before. On the voyage out all had done their duty, and all had been in the boats as usual. One of the crew was taken sick […] when one of the crew came aft […] and informed the captain that one of the crew in the forecastle who went by the name of George Johnson was a female! It very much surprised him, as well as all on board, and the man was told to go forward and send George into the cabin. He did so, and George made his appearance. The Capt. after interrogating her gave up a birth [sic] in his cabin for her and immediately put back to Peyta [Paita, Peru], gave her $100 and sent her home on board a vessel.

I learned from Eric Jay Dolin’s Leviathan: The History of Whaling in America (pp. 237-40), as well as other sources, that the woman was 19-year-old Ann Johnson of Rochester, N.Y. Her identity was discovered in July 1849 when (ahem) some of her clothes fell away in a feverish delirium. Why had Johnson dressed as a man and joined the crew of the Christopher Mitchell? Well, her story made the newspapers, but contemporary accounts varied widely, and historians haven’t been able to come to a consensus. Here’s Sullivan’s explanation:

She said in her story that she was decoyed away from home, Rochester, N.Y. by a man with whom she lived a few months when he left her, that she then went to her home but was forbid to enter by her father, that she then went and dressed in boy’s clothes, and went to ride horse on the canal, towing boats; that afterwards she went into a shipping office and asked for a birth [sic] on board a ship in the capacity of cabin boy, but finding no encouragement consented to ship as a youngster in a whaler. That she was sent to Nantucket and engaged by the owners of this vessel. Romantic truly!

I can’t say whether this version is definitive, but Hawley was hearing it from the captain himself only one month after it happened. Amazingly, Johnson had been able to maintain her disguise for seven months!

The story of Ann Johnson reminded me of another female sailor I learned about earlier this year when I cataloged the letters of Augustus Percival. Her name was Abbie Clifford, and she sailed with her husband, Captain Edwin Clifford, on a brig that bore her name. The Cliffords were from Maine. Percival served as their first mate in 1869 and mentioned them often in letters to his wife back in East Orleans, Mass.

The Abbie Clifford was engaged in the China trade, and in the fall of 1869, the ship was anchored at Shanghai waiting for a freight of tea. Percival occupied the cabin adjoining the Cliffords, and the three often ate and talked late into the evening on a variety of subjects, including religion. His letters reveal an unmistakable affection for the “free hearted” couple and an admiration, especially, for Mrs. Clifford.

Mrs Clifford is quite a Sailor, has been over 10 years with the Capt and I dont know as she has missed a voyage since he has been Master. She is a fine looking woman, and very pleasant, and quite a talker. [24 September 1869]

She lets me see all the things she buys on shore and I like her much, and we have all got along first rate so far, and hope we shall continue the same, but I know he is a very timid man & very nervous, but then he has much to worry him. [5 October 1869]

Every day brings us nearer a Charter, but he is almost discouraged at times, while She is always looking on the bright side, which is proper. [9 October 1869]

The end of November 1869 found the Abbie Clifford at Swatow (now called Shantou) chartering to take hundreds of “coolies” to Singapore. Percival’s intimacy with the Cliffords had only grown. He described the captain in fraternal terms and continued to praise Mrs. Clifford for her seafaring abilities, as well as her domestic qualities.

Mrs. C. generally looks after his Books, and is very good in figures and is a very good Navigator also and works time for the Capt or did on the passage out. [4 December 1869]

It seems good to live in such a friendly way, and as it seems good to have some one to confide in, I say many things to Mrs. that I do not to others, and she is very good to me, will sew on a Button, offered to mend my Socks, &c. [6 December 1869]

By December 1870, Percival had moved on to another ship. But events of 1872 proved his admiration for Abbie Clifford very well-founded.

That spring, off the coast of Pernambuco, Brazil, yellow fever ravaged the Abbie Clifford, killing at least five crew members, including the steward, first mate, and Captain Clifford. When Percival heard the news, he wrote to his wife about Mrs. Clifford: “I pity her, but trust she will bear up under her trials with Christian fortitude.”

That she did. After her husband’s death on 5 April 1872, Mrs. Clifford (according to some accounts, suffering from yellow fever herself) gamely took command of the ship and sailed the thousands of miles north to New York, with the help of those men well enough to work. On the way, the crew withstood a five-day gale above Cape Hatteras that destroyed several of the ship’s spars and sails. They arrived at their destination on 12 May 1872.

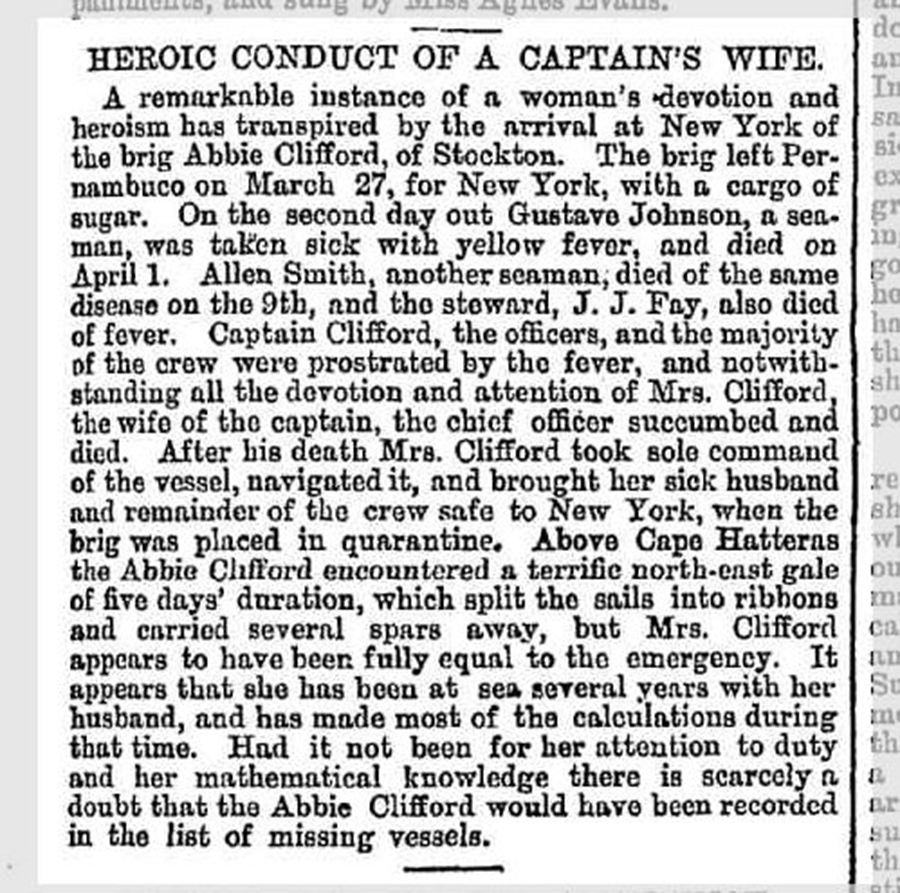

Abbie Clifford’s exploits were recounted in glowing terms in newspaper articles of the day, like this one from as far away as Australia:

And as early as 1883, she was profiled in books like Daughters of America; or, Women of the Century (pp. 716-7) alongside some of the greatest 18th- and 19th-century American women. The Illustrated History of Kennebec County, Maine (pp. 757-8), published in 1892, mentions Abbie Clifford’s second marriage in 1877 to George Brown and goes on to describe her like this:

Mrs. Brown is a lady of genial bearing, a broad, well disciplined mind, and rare courage. She made several sea voyages with Captain Clifford, who commanded vessels in the merchant service. While on these voyages she studied navigation as a pastime, and when the necessity came of putting her knowledge of chart and compass to the test, her courage was not wanting.

Abbie J. Longfellow, later Clifford, later Brown, was born in 1839, which would make her only 32 or 33 at the time of her triumphal return to New York at the helm of the Abbie Clifford. She died in 1901.