By Susan Martin, Processing Archivist & EAD Coordinator

I have now to tell you of a pretty important step that I have just taken. I have given my name to be forwarded to Massachusetts for a commission in the 54th (negro) Regt. Coln. Shaw.

This excerpt comes from a letter written by Civil War soldier William Harris Simpkins on 26 February 1863. Harris was serving with the 44th Massachusetts Infantry at New Bern, N.C. and had been recommended for a post in the new 54th Regiment, the first African American regiment raised in the North. Simpkins decided to accept and, in this letter to his father, preemptively defended his decision and discussed the possibilities of the regiment.

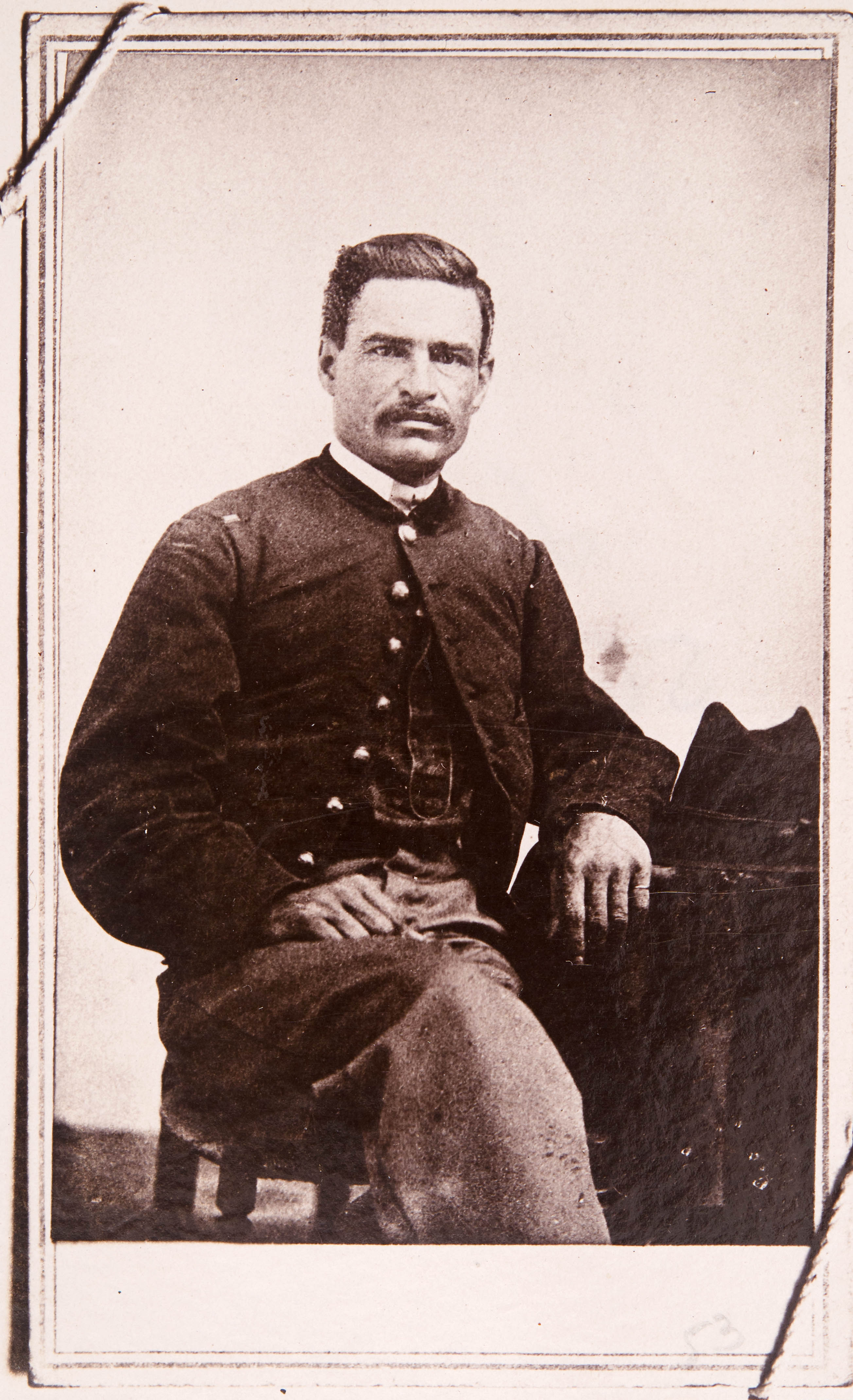

William Harris Simpkins (1839-1863)

Simpkins was born in Boston, Mass. on 6 Aug. 1839 and worked as a clerk before enlisting in the Union Army. When he got word from Col. Francis L. Lee that he had the chance at a commission with the 54th under the command of Capt. Robert Gould Shaw, he was cautiously optimistic. He recognized the significance of the move and acknowledged what he might be giving up. Portions of his letter have been printed in histories of the regiment, but I think it’s worth quoting at length.

This is no hasty conclusion, no blind leap of an enthusiast, but the result of a considerable hard thinking.

It will not at first, and probably will not be for a long time, an agreeable position for many reasons too evident to state, and the man who goes into it resigns all chances in the new white Regiments, that must be raised; […] and there can be no dispute as to, among which color, the most comfortable & pleasurable position will be.

Simpkins’ friend Cabot Jackson Russel saw things in a similar light. The 18-year-old Russel served with Simpkins in the 44th and was also commissioned a captain of the 54th. Just one day before Simpkins, on 25 Feb. 1863, Russel wrote home to say that he had “given up everything” and was “going under Bob Shaw, as it seems so important to put this measure through.” (Russel’s letters can be found in the Patrick Tracy Jackson and Loring-Jackson-Noble family papers.)

Cabot Jackson Russel (1844-1863)

Despite the risks and the uncertainty, Simpkins still believed in the project. His letter continues:

Then it is nothing but an experiment after all. But it is an experiment, that I think it high time we should try; an experiment, that if successful, will be productive of much good; […] an experiment, which the sooner we prove unsuccessful, the sooner we shall establish an important truth and rid ourselves of a false hope.

Some publications stop quoting him there, but I found the next paragraph particularly moving.

There will probably be some trouble with the white troops in the field, arising from a traditional sence [sic] of honor, too nice for me to understand, which distinguishes between fighting behind earth-works thrown up by black laborers, and allowing a negro soldier to stand in the next field to fire his gun at the common enemy; but once prove the efficacy of black troops and I think they will hail them, as drowning men catch at straws.

To make the test you must have men who are willing for the trial. It is of especial importance, of course, in order to win the people to this movement, that it should be undertaken by the right sort of men, and that the first black Regt. should have everything done for it in the way of officers &c that would tend to make it efficient. If I am one of the persons selected, why should I refuse? I came out here, not from any fancied fondness of a military life, but to do what I could to help along the good cause. Why should I not stretch my patriotism a little further and accept a commission in a Negro Regt?

Simpkins was killed on 18 July 1863 during the assault at Fort Wagner as he kneeled next to his injured friend Russel. The 1864 memorial to Robert Gould Shaw includes a detailed description of Simpkins’ death, which was witnessed and recounted by Sgt. Stephen A. Swails.

Stephen Atkins Swails (1832-1900)

Simpkins, Russel, Shaw, and the black soldiers killed in the battle were buried together in a mass grave.

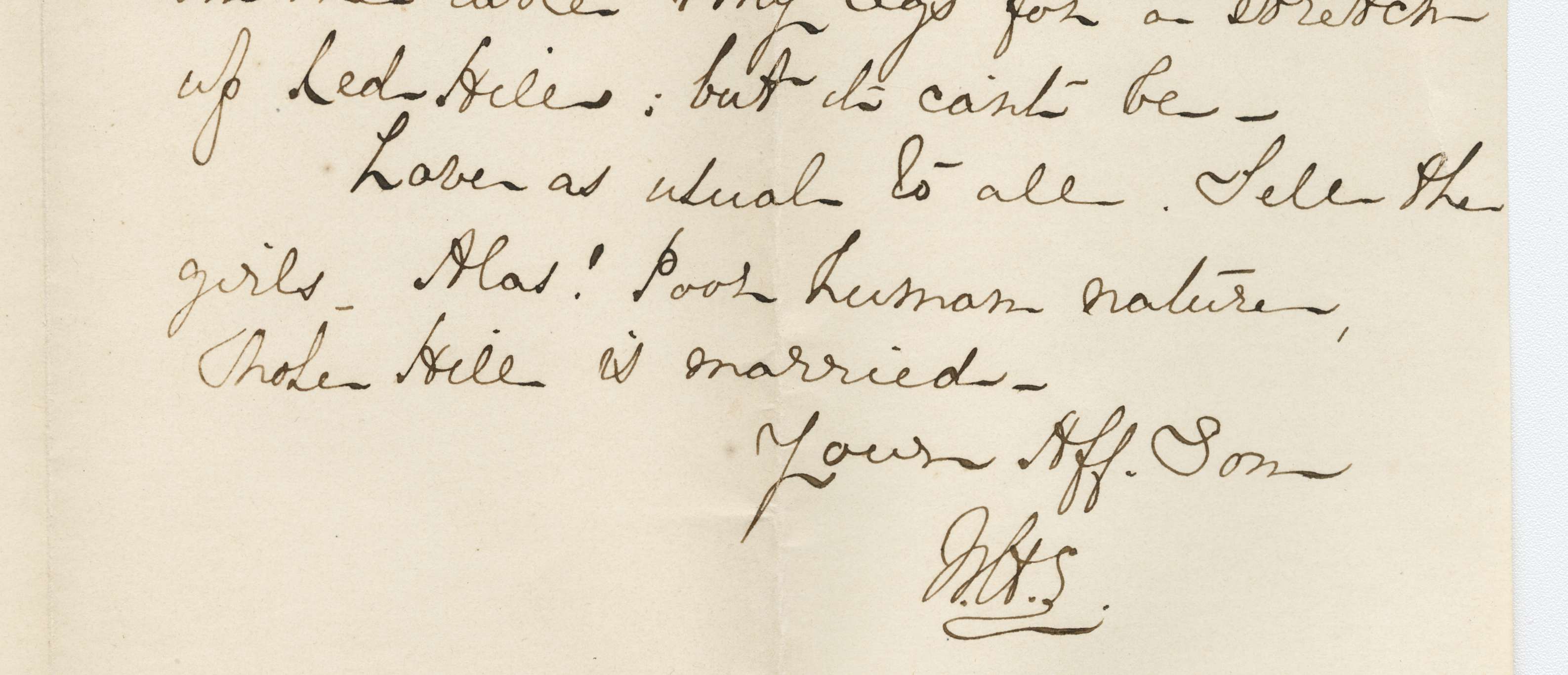

Simpkins’ letter forms part of the Hooper family papers here at the MHS—his aunt married into the Hooper family, and his cousin Henry Northey Hooper also served as a captain in the 54th Regiment. Unfortunately the document we have is only a copy written by someone else, and the location of the original is unknown. However, the Hooper collection does contain two original letters by Simpkins, written to his mother before he enlisted.

The Massachusetts Historical Society has many resources related to the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, both online and in our library, including manuscript collections, photograph collections, and print material. You’ll find a handy introduction here.