By Sara Georgini, The Adams Papers

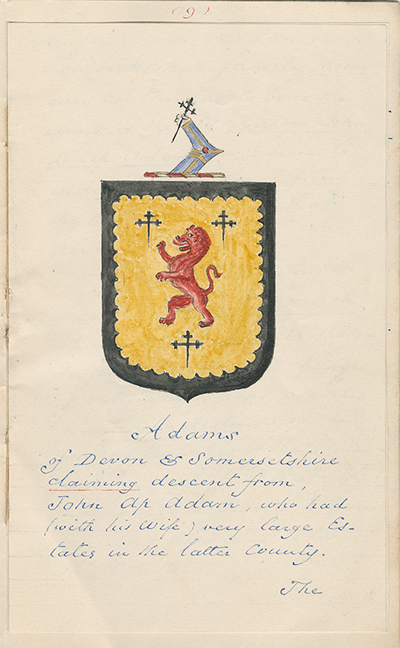

John A. Grace, Memoranda Respecting the Families of Quincy and Adams, 1841

For historian Henry Adams, the morning mail meant a fresh round of research questions. “Here comes your troublesome genealogical cousin again,” Elizabeth Coombs Adams wrote in early 1893. Paging through the Adams archive and sweeping up reminiscences to file, Elizabeth was laboring to compile the family history. She joined a long train of Adamses who devoted time and money to polishing up new accounts of their genealogy. Knee-deep in piles of stray notes and record scraps before the likes of research hubs like Ancestry.com, they turned to wheels, charts, and trees to draft the presidential family’s Anglo-American origins story. Today, let’s take a quick look at the Victorian Adamses’ adventures in genealogy, and who they thought they were.

John Adams and son John Quincy picked through family memories and town records to uncover and curate their version of the early American past. Piecing together shared evidence did not yield the same story. Father and son split over the exact region of their English roots. But both presidents staked claim to a Puritan lineage that played well with constituents. Highlighting their role in the Puritan ordeal of suffering, immigration, and settlement, the Adams statesmen linked themselves to a history of religious toleration and political dissent. When it came to genealogical pursuits, their methods varied, too. The elder Adams’ approach to genealogy was impulsive. He dashed off “minute” memoranda of random finds, listing births and deaths as he encountered them in odd pages of his father’s books. Strategically, he wove Puritan family ties into the revolutionary rationale that powered his Dissertation on the Canon and the Feudal Law (1765).

John A. Grace, Memoranda Respecting the Families of Quincy and Adams, 1841

His son, John Quincy, approached the task with trademark rigor and a passion for verification. Highly scientific and systematic in his effort, the sixth president scoured town records and newspapers, copied out church membership lists, and checked material in his family papers against those of other early Americans. John Quincy’s scholarly bent for fact-checking was aided by a rising set of organizations that steered the antebellum practice of personal history, like the Massachusetts Historical Society (1791), the Boston Athenaeum (1807), and the New England Historic Genealogical Society (1845). More than a hobby to fill the diplomat’s rare downtime, genealogy was a way for John Quincy to exercise his skills as a gentleman scholar. It was a task to pass along across the generations, and so he handed it off to his son, Charles Francis, with the family’s large set of seals and copper bookplates. On 28 Feb. 1831, he laid down what he knew of the Adams ancestry and colorful heraldry in a detailed missive. “File this letter away,” John Quincy instructed, “for the age when the passion of genealogy shall take possession of you.”

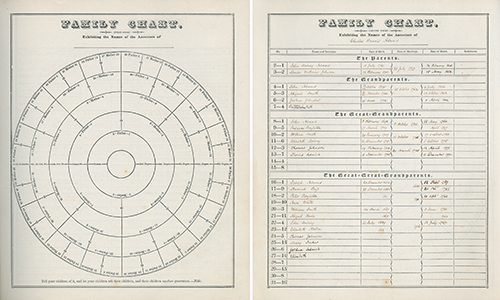

Stoked by his highly successful publication of Abigail Adams’ letters in 1840, Charles’ interest in the family past blossomed steadily throughout his life. Like many Americans, he invested in Lemuel Shattuck’s Family Register book. The blank album featured tidy charts and wheels to organize the machinery of family for presentation. Stocked with a template narrative for each ancestor and stern guidelines for nascent family historians, Shattuck’s book commanded that facts–and not opinions–must guide the process. There were, Shattuck lectured, many kinds of facts to collect, and they should be updated on a monthly basis. His categories veered from the mundane to the moral: health, religious tendencies, phrenological oddities, children’s expenses, real estate descriptions, vaccinations, public offices held, and “plans for private intellectual improvement.” Dutifully, Charles began the book, making lists and skipping the intricate wheels. He never finished it, likely thinking that the family’s cache of letterbooks, correspondence, and diaries filled in the rest.

Charles Francis Adams, entries in Family Register, 1841

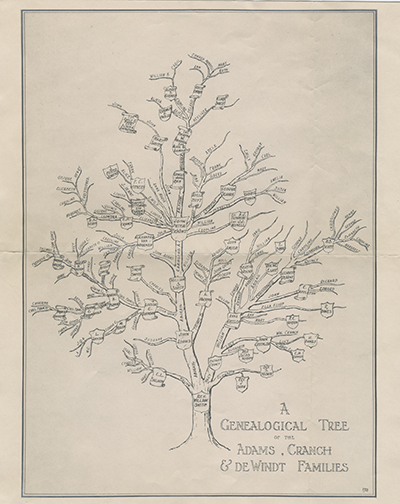

Or maybe Charles realized he didn’t need to do all the research alone. Genealogy had, after all, evolved into a new American pastime. By 1841, at least one reader of Abigail’s published letters reached out (from Havana!) with new clues to the more distant Adamses. John A. Grace delved into the complex English roots of the Adams, Quincy, and Boylston lines. To Charles, he sent a vivid, hand-colored memorandum of the Adamses’ related heraldic arms with details cobbled together from foreign records. Grace put forth an idea that Charles and his children, including Henry, came to champion: that the family descended from the Welsh baronial clan of ap-Adams. Over time, more Adamses went on to swarm the archives, eagerly hunting for familiar faces in history’s mirror. Henry Adams, holding his cousin’s query, sniffed that he did not “invest in the genealogy.” But, as the Adams Papers reveal, Henry made just as many charts as others did, diligently tracing out his great grandparents’ lines on graph paper (see Reel 603 of P-54, the Adams Family Papers microfilm). Even Henry Adams could not resist family history forever.

A Genealogical Tree of the Adams, Cranch, & DeWindt Families, 1928