By Peter Drummey, Librarian

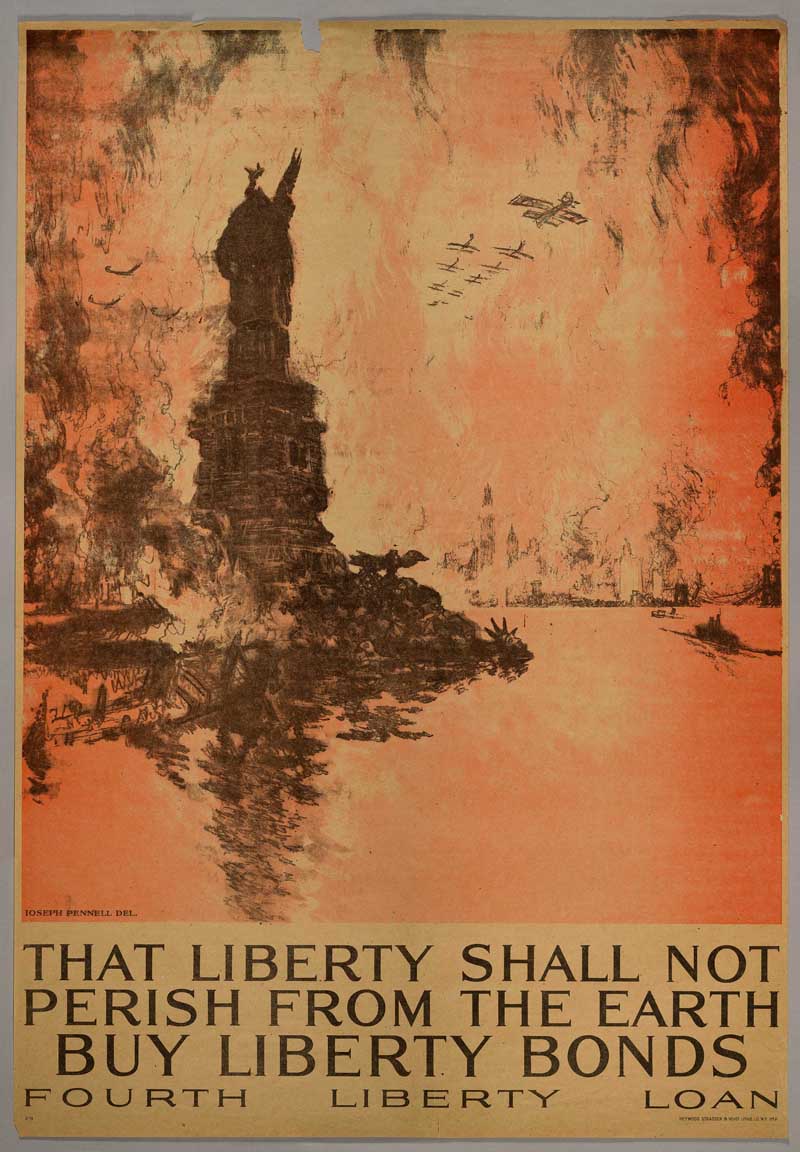

Joseph Pennell originally titled his dramatic depiction  of war-ravaged New York City, a poster he created during World War I for a patriotic loan drive, “Buy Liberty Bonds or You Will See This.” In 1918, the idea of New York under aerial bombardment and in flames would have seemed to be a fantasy, but Pennell’s lithograph contained one element that reflected actual events a century ago. In the poster, just to the right of the decapitated head of the Statue of Liberty, the sinister shape of a German submarine glides through New York Harbor. In the summer of 1918, “U-Kreuzers,” German long-range submarines, patrolled off the coast of Long Island where, at night, crewmembers could see light cast by the “Great White Way” of Manhattan on the horizon. The threat of enemy attack had come to North American waters and would soon arrive off the shores of Cape Cod.

of war-ravaged New York City, a poster he created during World War I for a patriotic loan drive, “Buy Liberty Bonds or You Will See This.” In 1918, the idea of New York under aerial bombardment and in flames would have seemed to be a fantasy, but Pennell’s lithograph contained one element that reflected actual events a century ago. In the poster, just to the right of the decapitated head of the Statue of Liberty, the sinister shape of a German submarine glides through New York Harbor. In the summer of 1918, “U-Kreuzers,” German long-range submarines, patrolled off the coast of Long Island where, at night, crewmembers could see light cast by the “Great White Way” of Manhattan on the horizon. The threat of enemy attack had come to North American waters and would soon arrive off the shores of Cape Cod.

July 21, 2018, marks the 100th anniversary of the only attack on American soil—although probably inadvertent—during the First World War. On that summer Sunday morning, 21 July 1918, while shooting at the tugboat Perth Amboy and its towline of four large barges off Nauset Beach in Orleans, on Cape Cod, Massachusetts, the German submarine U-156 fired shells that passed over their intended targets and landed on the beach. Town residents and vacationers, attracted by the rumble of artillery fire, gathered to watch the “Battle of the Barges,” also known as the “Battle of Nauset Beach.”

Dr. Joshua Danforth Taylor of East Boston, a loyal subscriber to the Boston Globe, telephoned the Globe newsroom from his vacation cottage overlooking the scene to give the editors and reporters, in real time, a blow-by-blow (shell-by-shell?) account of the one-sided “battle.” Almost miraculously, although some of the barge captains were accompanied on their ships by wives and children, there were only two serious injuries, both to members of the Perth Amboy’s crew. The casualties, John Bogovich and John Zitz, turned out to be immigrants from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, then at war with the United States, so Bogovich and Zitz—although badly wounded—fell under suspicion of playing some sort of nefarious role in the attack.

As shown in the accompanying photographs (deck of tug / side of tug) , the Perth Amboy was badly damaged by shell fire and abandoned by its crew, but it survived the attack. The four barges were all sunk. Prompt action by the Coast Guard and local fishermen saved the barges’ crews, families, and even a ship’s dog named Rex. Jack Ainsleigh, a young son of the master of the sail barge Lansford, became an instant celebrity when he waved the American flag as his family abandoned ship and threatened to return the 150 mm cannon fire from the U-156 with his .22 caliber rifle.

The U-156 disappeared with all hands in September 1918 during its voyage home to Germany, probably sunk by a British or American mine in the North Sea, so some of its operations are conjectural or based on intercepted radio messages, but its presence off Nauset Beach probably had more to do with an attempt to cut the transatlantic telegraph cable to France that came ashore in Orleans than to sink empty coal barges and scare/thrill the local population. If cable cutting was the U-156’s mission that day, it failed, but the U-Kreuzer already had delivered a heavy blow: the mines it laid off the coast of Long Island sank the armored cruiser San Diego on 19 July, the largest U.S. warship lost during the war.

With no loss of life to darken the story and many human interest elements to enliven the very heavy press coverage of the event, the “Battle of the Barges” seems a long-ago and somewhat bizarre summer adventure at the beach for the people who witnessed it. The U-156 was a technological marvel, but it devoted most of its voyage to destroying sail-powered American and Canadian fishing vessels. Nevertheless, the German long-range submarine campaign in 1918 was, in some respects, a rehearsal for the much more dangerous and successful German U-boat operations in North American waters during the Second World War.

The photographs of the Perth Amboy after it was salvaged and towed into Vineyard Haven on Martha’s Vineyard are from the diary of Charles Henry Wheelwright Foster, an avid yachtsman, who inserted them between his entries for August 1918, but otherwise made no note of the attack on Orleans or the presence of German submarines along the coast. Joseph Pennell’s Liberty Loan poster is from the Massachusetts Historical Society’s large collection of World War I posters, many the gift of Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, the president of the Historical Society during the war.