By Susan Martin, Collections Services

The MHS recently acquired two fascinating letters related to a woman named Nancy Barron, and when cataloging the collection, I found a surprising connection.

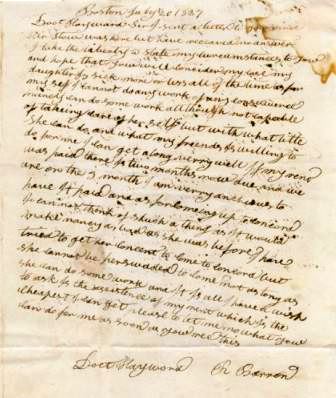

The first letter, addressed to Dr. “Hayward” of Concord, Mass., was written on 20 July 1827 by R. Barron, Nancy’s mother. The Barrons lived in Boston. The letter begins:

Sir I sent a letter to you since Mr Stow was here but have receaved no answer. I take the liberty to state my curcumstances to you and hope that you will concider my case. My daughter is sick more or less all of the time. As for myself I cannot do any work of any consequence. Nancy can do some work all though not capable of takeing care of herself.

R. Barron asked the doctor for help with their rent, which was two months overdue, and explained that she and her daughter couldn’t come to Concord “as it would make Nancy as bad as she was before.” The family received some charity, but it wasn’t enough.

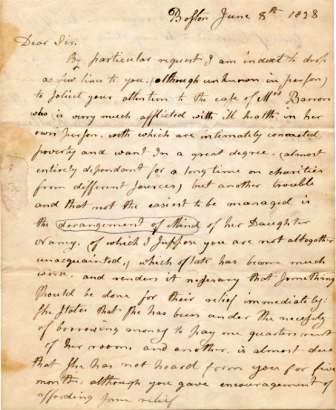

The only other letter in the collection was written almost a year later, this time to Dr. “Haywood.” The writer, D. Patten of Boston, pleaded on behalf of the Barrons, for whom circumstances had deteriorated. Mrs. Barron was “verry much afflicted with ill health,” and the family suffered “poverty and want in a great degree.” Adding to these troubles was Nancy’s “derangement of Mind […] which of late has become much worse.”

Just identifying the correspondents in this small collection was challenging. The two letters were clearly written to the same person, but spelled his name differently. I started with him, assuming he’d be the easiest to find. It took some digging, and through trial and error, I finally stumbled on Dr. Abiel Heywood (1759-1839). Neither Barron nor Patten had spelled the name right.

According to a biography of Heywood published in Memoirs of Members of the Social Circle in Concord (pp. 228-33), he began practicing in Concord in 1790, though he soon left medicine to serve in a series of public positions, including town clerk, selectman, tax assessor, justice of the peace, and Middlesex County judge. He was a very eminent member of the community in 1827, when Mrs. Barron appealed to him.

I never did identify the writer of the second letter, D. Patten. I also don’t know the first name of Nancy’s mother. But when I started looking for Nancy, I found more than I expected. A Google search turned up her name in, of all places, the journals of Ralph Waldo Emerson.

The relevant journal entry is dated 24 June 1840. By this time, Nancy was living at the Concord Asylum, an almshouse just 200 yards behind Emerson’s home, across the Mill Brook. The reference to her is unexpected and startling. Emerson wrote:

Now for near five years I have been indulged by the gracious Heaven in my long holiday in this goodly house of mine, entertaining and entertained by so many worthy and gifted friends, and all this time poor Nancy Barron, the mad-woman, has been screaming herself hoarse at the Poor-house across the brook and I still hear her whenever I open my window.

Ralph L. Rusk, who edited the published volumes of Emerson’s letters beginning in 1939, included citations for a few letters related to Nancy, but he misread her last name as “Bacon.” The error was corrected in an annotation in volume 7 (p. 336) by subsequent editor Eleanor M. Tilton. Apparently, between 1839 and 1843, Emerson corresponded with a Mary Mason about Nancy’s case; these letters are currently on deposit at Harvard’s Houghton Library. It seems Emerson and others provided financial support for Nancy’s care, which would account for how he knew her name.

Like his neighbor Abiel Heywood (the land adjacent to Emerson’s home is still called Heywood Meadow), Emerson belonged to the Social Circle in Concord, a private club for illustrious men of the town. Also among its members was Cyrus Stow—undoubtedly the man R. Barron mentioned in her letter. According to the Memoirs (pp. 295-301), Stow contracted with the town “to take charge of its poor for the use of the Cargill Farm.” Concord Asylum was located on Cargill Farm, probably near where the police and fire department building stands now. Stow was the last piece of the puzzle.

The only other result of my search for Nancy was a single line in the register of births, marriages, and deaths in Concord: “Nancy Barron aged 46 years died March 29, 1843” (p. 355). Emerson acknowledged her death in his correspondence with Mary Mason.

The striking juxtaposition of Nancy Barron and Ralph Waldo Emerson, with just 200 yards and a narrow brook between them, may have been the kind of thing Henry David Thoreau had in mind when he wrote the following passage in Walden (p. 172):

But how do the poor minority fare? Perhaps it will be found, that just in proportion as some have been placed in outward circumstances above the savage, others have been degraded below him. The luxury of one class is counterbalanced by the indigence of another. On the one side is the palace, on the other are the almshouse and “silent poor.”