By Susan Martin, Collections Services

This is the seventh and final post in a series about the wartime experience of Charles Cornish Pearson. Go back and read Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV, Part V, and Part VI for the full story.

We’ve come to the conclusion of the story of Sgt. Charles Cornish Pearson and his service with the 101st Machine Gun Battalion during World War I. We pick up after the Battle of Saint-Mihiel in September 1918, a success for the Allies, who forced the German line back and captured thousands of prisoners and hundreds of guns. Loved ones back in the States were thrilled by the news. Charles wrote to his Aunt Florence:

Suppose the news in the paper the past few weeks has cheered up the people at home a good deal. Certainly is quite a set back to the Hun but guess they need a lot of licking yet before they see the error of their ways in the proper light. One doesn’t appreciate the havoc & needless vandalism they have carried on until one has travelled over this part of the country & then one hasn’t taken into consideration the slavery the civilian population has had to undergo the past four years. They sure have a lot to pay for if they ever can.

Despite rumors that the war was winding down, Charles knew his “next trick” would come soon, and he was right. Less than a month after Saint-Mihiel, on 8 October 1918, his battalion moved to the outskirts of Verdun to prepare for its part in the brutal Meuse-Argonne Offensive. Philip S. Wainwright points out, in his History of the 101st Machine Gun Battalion, that from this position the men could see the infamous Mort-Homme, the site of terrible losses in the Battle of Verdun two years before. Another soldier described the feeling of being surrounded by “numberless French graves” (p. 124).

From 23-31 October, the guns of the 101st were used to support an attack by the 26th Yankee Division at the Bois de Brabant-sur-Meuse. According to Wainwright, it was the hardest fight the battalion had ever faced, with “continuous shell-fire” and “gas attacks every night” (p. 52). Charles agreed. On 1 November, after a gap of 17 days, he wrote to his parents from a reserve position at Marre, and his usual breezy style was muted.

One doesn’t feel much in the mood for letter writing. […] Things have been happening pretty swiftly lately and I feel pretty lucky to be able to scribble you a line & say O.K. […] Suppose I could write you a great deal about what we have been doing the past days but am only too glad to be out of it for the time beginning [sic] & just say that war is h–l & let it go at that.

He told his brother Bill, in a bemused tone, “I often wonder how they all missed me and the others. Fate I guess with good dodging is the answer.” In a letter to his sister Jean, he included some very vivid details of the battle—huddling in a trench as shells flew overhead, the spray of dirt as “whiz bangs” hit the hill opposite, the hardness of the ground. He also switched seamlessly to the present tense and second-person pronouns, making his story even more visceral: “You try to sleep saying to yourself well you are pretty safe unless they make a direct hit…” But as for the worst of his experiences, he explained, “I am getting so now I try to forget all about them as soon as they are over and sometimes that is no easy thing to do.”

Rumors of peace were coming in fast and furious now. As one soldier put it, “this war is all over but the shooting” (Wainwright, p. 131). Sure enough, at 11 a.m. on 11 November 1918, the armistice went into effect. This description of that moment doesn’t come from Charles, but from another soldier quoted by Wainwright:

Suddenly there is a queer silence—we don’t know what to think or do. It is true—but no one wants to shout or laugh. We just cannot realize the significance of it. Here we were, only a few moments ago, ready to jump into our cars and go out and shoot up the Boche, or get shot up. What will happen, and where are we going now? (p. 132)

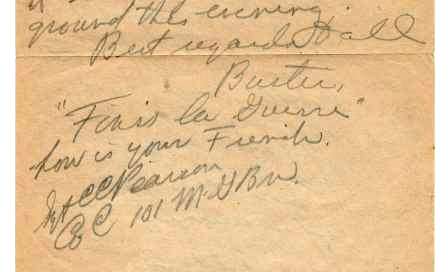

Charles, like others, was both stunned and relieved that the war was over. He wrote to his parents the following day, “It seems too good to be true & one wanders around in a daze. It sure has been h–l at times but guess it has been worth it all.” And he signed off another letter with the words: “Finis la Guerre.”

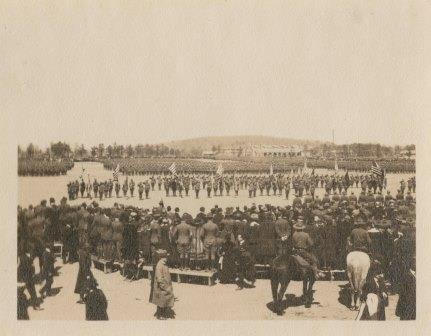

Charles looked forward to getting back into civilian clothes, rejoining the commercial paper business, and doing “as I damn please for awhile.” He even asked his sister if she knew any single girls who would be interested in a “perfectly harmless veteran.” But he would have a long and frustrating wait of several months before the 101st Machine Gun Battalion finally sailed for home in the Agamemnon on 31 March 1919. Charles was discharged on 29 April 1919.

Charles married Edith Irene Carrier in 1925. He died on 19 May 1973 at the age of 83, survived by his wife, three children, six grandchildren, and one great-granddaughter.

In spite of his humble protestations, Charles was a very compelling correspondent, and I hope you’ve enjoyed this deep dive into his papers as much as I have. I’ll finish with an excerpt from a letter to his sister, written from France after the war:

Glad you have appreciated or rather enjoyed my letters written over here. Am afraid you over exaggerate as I never was much of a hand at letter writing and my power of description etc is sadly lacking, still if they gave you some idea of what we have been doing over here why I am satisfied.