By Brendan Kieran, Reader Services

The Rockwood Hoar Papers at the MHS document the life and career of Rockwood Hoar, a Worcester, Massachusetts lawyer and politician who lived from 1855 to 1906. Hoar was the son of United States Senator George Frisbie Hoar, and he served in Congress himself toward the end of his life. Among Hoar’s papers are his legal files which are arranged alphabetically by client name, including immigrants from various countries. I looked into these files and focused specifically on the file relating to Ideem Fatool,* a Worcester resident who was, according to a September 1905 Hoar letter (a copy of which is in the collection), Syrian. Through my reading of these materials I got a sense of the research possibilities these papers offer for anyone studying the experiences of immigrants in late 19th- and early 20th-century Massachusetts.

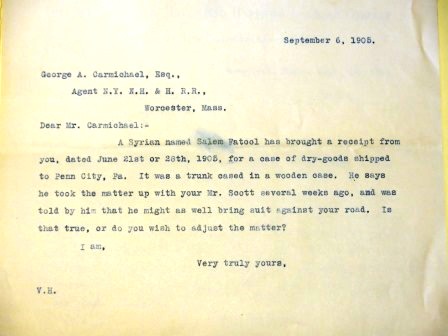

Copy of a 6 September 1905 letter from Rockwood Hoar to George A. Carmichael of the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad

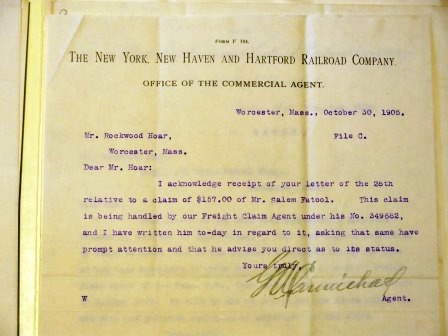

Ideem Fatool lived at 31 Norfolk Street in Worcester and worked in “rugs” in 1905, according to the 1905 Worcester Directory (p. 238; Fatool’s first name is listed as “Saleem” in this directory). His file relates to a claim he made with the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad after a trunk of goods he shipped was lost along the way to its destination in Pennsylvania. In an undated typescript copy of a letter addressed to the railroad company, Fatool lists items in the lost shipment along with their values. He lists the total value of the goods as $157. His letter is followed by correspondence between September 1905 and March 1906, primarily involving Fatool’s lawyers and railroad representatives. Hoar writes to railroad agent George A. Carmichael about the issue in September. Carmichael responds the following week indicating that the railroad would require more information, and writes again in October to state that he is passing the dispute along to Boston freight claim agent T. C. Downing.

In November and February letters, Downing follows up with additional details relating to the status of the claim, and writes in his February letter that, without additional evidence, they would not accept Fatool’s statement relating to the value of the goods as accurate. Hoar sends information about the case to another lawyer, Charles F. Aldrich, in a February letter, and a Downing letter sent the following month is addressed to Aldrich. Downing writes that the company believed Fatool claimed the goods to be worth five times more than they actually were, and in a xenophobic comment, attributes this to the fact that Fatool was an immigrant and implies that he was likely looking for money from the company.

Rockwood Hoar to George A. Carmichael, 30 October 1905.

The last two items in the folder are February and March 1906 letters written from Aldrich to Hoar. These letters contain updates relating to the case. In both letters, Aldrich writes that Fatool had left the country, but the lawyer doesn’t seem certain of Fatool’s destination. In his 27 February 1906 letter, he writes that “Fatool has gone back to Europe,” and in his 6 March 1906 letter, he writes that “Fatool has gone back to the interior of his native country, which is Syria or Armenia, I am not sure which.” In his final letter, Aldrich notes that he is still attempting to find out more from the company about the issue, but it seems that he had hit a roadblock.

The materials in this file provide some glimpses into the Worcester of the period and the ways that immigrants helped to shape it. The list of goods in Fatool’s shipment includes wool, perfume soap, a silk spread cover, a quilt, drawnwork, and other items. Additionally, the folder includes a card for Orfalea Bros. & Co. in Worcester. The card lists laces, drawn work, Turkish rugs, and kimonas as some of the items they sold. The card also lists various cities and countries in the Middle East, Asia, and Europe from which they imported items. These items provide brief but insightful evidence of international trade networks of the period and invite further research into the roles Syrian immigrants to the United States played within these networks and within the Worcester community.

On a side note, I took to the Internet to see if I could find out anything else about Fatool, and interestingly, according to a blog post by Chet Williamson of Jazz Riffing on a Lost Worcester, a Saleem Fatool was the father of Nick Fatool, a noted drummer born in Millbury, Massachusetts who played with Benny Goodman and other acts in the mid-20th century. Williamson references Millbury birth records that give Syria as the country of origin for Nick Fatool’s parents. A little more digging would be required to confirm whether or not this Saleem Fatool was the same individual as the person I write about in this post, so I can only speculate at this point, but this was an exciting find, and the fact that I also play the drums made it particularly exciting for me.

If you are interested in looking at the Rockwood Hoar Papers, feel free to view them here in the MHS library. Most of the collection is stored offsite, so library staff recommends requesting the materials through Portal1791 at least two business days before your intended visit, but they are otherwise open and available for research!

*****

*Fatool’s first and last names are spelled multiple ways by the correspondents in the file. The name “Ideem Fatool” is used here, as it is the one that is written on the folder and used in the collection guide. However, as noted in the text of this post, the spelling “Saleem,” which does not appear among the papers in Hoar’s file, is used in the 1905 Worcester Directory and in the sources cited by Chet Williamson in the Jazz Riffing on a Lost Worcester blog post, which makes me wonder if “Saleem Fatool” is the correct spelling of Fatool’s name.