By Susan Martin, Collection Services

This is the sixth post in a series about the wartime experience of Charles Cornish Pearson. Go back and read Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV, and Part V for the full story.

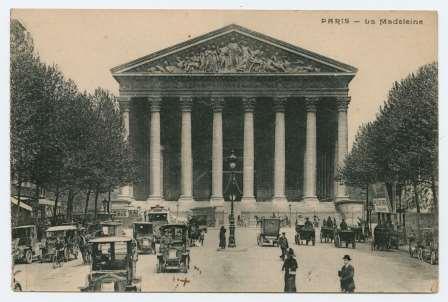

After the Battle of Château-Thierry on 18 July 1918, Sgt. Charles Cornish Pearson of the 101st Machine Gun Battalion, American Expeditionary Forces, was granted a 48-hour leave, so he went to Paris to see the sights. (These two days, 6-8 August, would be his only leave during the war.) Of course, he enjoyed the respite very much, calling Notre-Dame Cathedral “the most wonderful building I ever saw, but I haven’t spent all my time admiring buildings.” He sent postcards to his family back home, including one to his little niece from “Uncle Buster.”

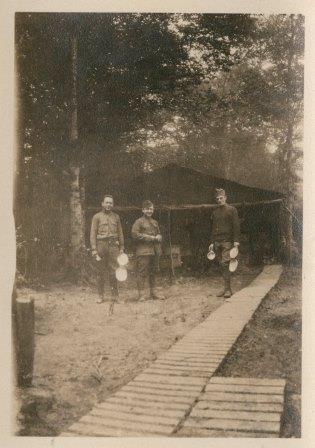

Just a few days after rejoining his battalion, Charles was on the road again. According to Philip S. Wainwright’s history, the 101st moved several times between mid-August and mid-September, first southeast to the town of Étrochey, then northeast again to the Rupt Sector. There the battalion took part in the Battle of Saint-Mihiel, which Charles described in an eight-page letter to his sister Jean, dated 15 September 1918. He began with his arrival at the front and what he saw as he came over a hill.

What a scene. Those guns had knocked those trenches some I can tell you, and the trenches were pretty well destroyed. Pill boxes, concrete dugouts & everything had been knocked to pieces in fine shape.

Charles spared Jean the grisly details—every letter had to pass the watchful eyes of censors, and the Censorship Bureau had forbidden any mention of casualties. But he did tell her about the grueling hikes to various positions, the sight of villages burning in the distance, and the capture of hundreds of German soldiers “who offered no resistance & seemed only too glad to be thru with the war.” The war was taking its toll on Charles, too, who wrote his Aunt Florence that same day, “It is great to be in all these drives but I tell you they are heart breakers and at times you wonder how you are going to keep going but still you manage it someway.” He longed for civilian life, but was proud of his service and the bravery and comradeship of his fellow soldiers.

A lot of Charles’ correspondence deals with items shipped back and forth between France and the U.S. His family sent care packages, and he sometimes requested specific items. For example, there’s this great insight into the life of a soldier:

Mighty glad to learn from Dads letter that you are sending a couple of books over. Any late popular & light fiction appeals to one over here. Of course one reads a great deal about the boys desiring the serious heavy stuff but far from it. They get too much of that in their days work. Any thing that will bring a smile is worth a thousand dollars I can tell you.

Meanwhile, Charles sent gifts home when he could, including a German helmet and gas mask for his nephew Bobby. “Suppose they are rather gruesome articles,” he admitted. He’d retrieved them himself from enemy lines after the German troops were driven off, weaving his way through the French trenches, across No Man’s Land, over barbed wire, and around shell holes—“havoc,” he called it, left by four years of fighting. He was impressed by the German trenches, though, some of which were 40 or 50 feet deep.

The spoils most prized by Allied soldiers were German pistols, belts, and belt buckles carved with the famous motto “Gott mit uns.” I don’t know if Charles ever found those, but he did send a second helmet to his brother Bill.

Picked yours up near a dead Hun. Didn’t quite feel like taking the one he had on although someone ahead of me had evidently cut his belt off for a souvenir. I am not quite so keen after souvenirs as that. Dont mind the sight of the dead but not very keen for handling them.

As always, Charles was humble about his letters. He wrote to Bill on 6 October 1918:

Am afraid my letters prove rather uninteresting reading as a rule. I don’t write an awful lot about this war stuff practically impossible to describe it in the proper way. It is a good deal made up of sensations and some of them aren’t especially pleasant.

Stay tuned for the seventh and final chapter of Charles Cornish Pearson’s story.